Remembering A Compassionate War Photographer

A few weeks ago the National Geographic lobby was so crowded with young schoolgirls I could barely make it to the elevators. The place was jumping with energy and I asked the ticket takers if the girls were here to see the Women of Vision photography exhibit. Indeed they were. It features the work of 11 National Geographic magazine photographers—Maggie Steber, Kitra Cahana, Jodi Cobb, Stephanie Sinclair, Amy Toensing, Lynn Johnson, Lynsey Addario, Beverly Joubert, Carolyn Drake, Diane Cook and Erika Larsen.

I was thrilled to learn that the young girls were here to see this wonderful work. At the same time it also brought a touch of sadness to my heart. I remembered another photographer who is no longer with us, Alexandra Boulat, who died after suffering a brain aneurysm in 2007 at the age of 45. She was a pioneer in her own right and her work belongs in the exhibit too. I miss her spirit, courage, wonderful eye and love of telling stories.

Boulat was born in Paris and in her youth studied graphic art, art history, and worked as a painter. In 1989 she joined Sipa Press, a French photo agency, and began her career as a war photographer. In 2001 she co-founded the VII Photo Agency, of which Sinclair and Addario are now members.

In a 2006 email exchange with me, she wrote: “Before I started to be a photographer I really had no idea yet about becoming a photojournalist. I became a photojournalist only because I was interested in stories, in journalism, in the life of people especially in extreme situations. My motivation to become a photojournalist was not influenced by pictures, but because of [the] incredible situation[s] some people were involved in.”

Boulat published six stories in National Geographic magazine and I was fortunate to have worked with her on four: Albanians: A People Undone, Feb. 2000; Eyewitness Kosovo, Feb 2000; Baghdad Before the Bombs, June 2003; and Diary of a War, Sept. 2003.

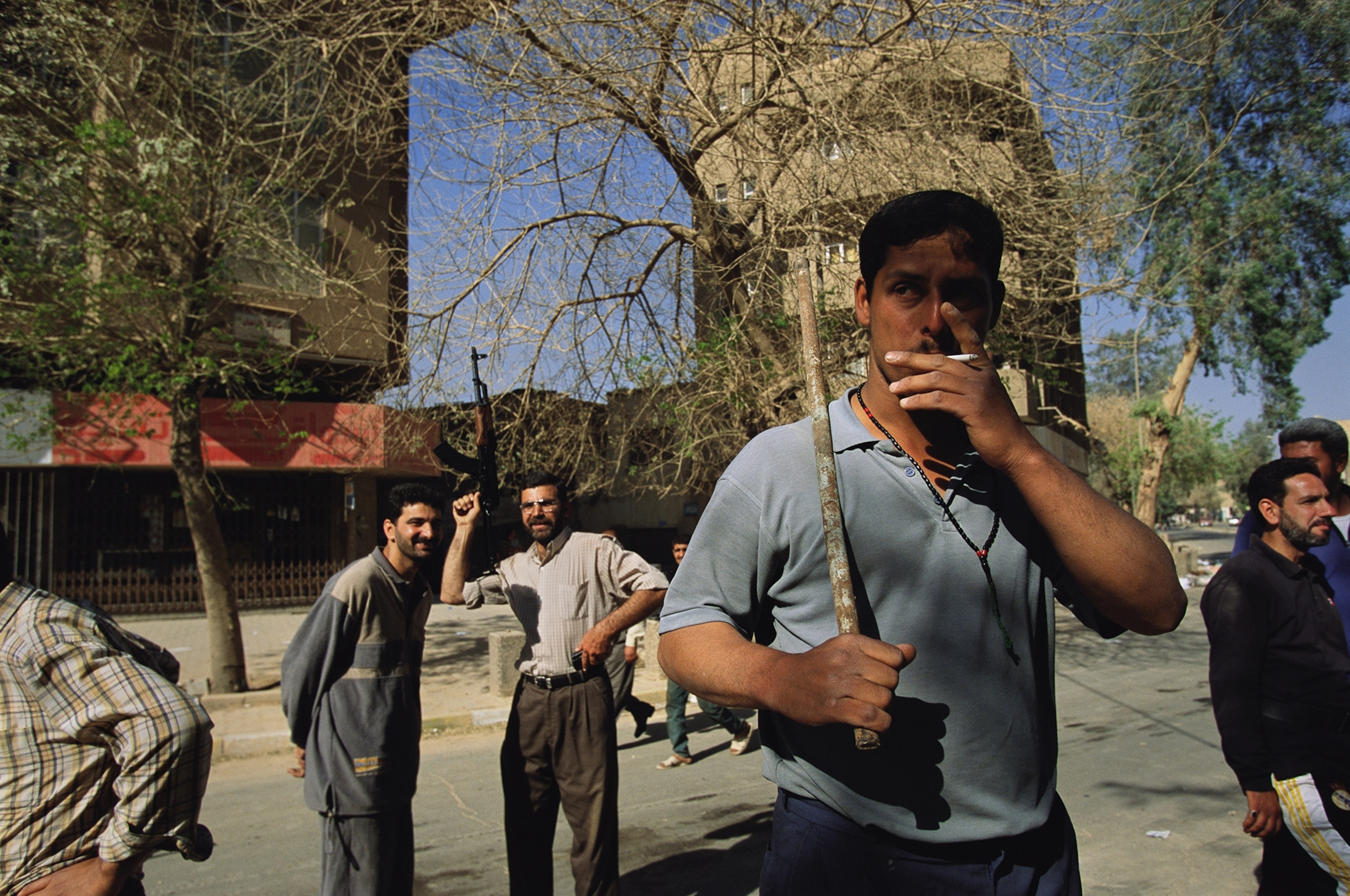

Boulat was no stranger to the battlefield, covering the Balkan conflict in the late 1990s. Always aware of the risk to her own life, she was driven to give voice to the unheard, to bear witness to the unseen, and to somehow make sense of all the madness. She was a rare soul who could take in the chaos of war and somehow make it viewable for the rest of us. In 2003, the magazine sent her to Baghdad ahead of the U.S. invasion to document the beginning of the Iraq War.

Before the invasion, Saddam Hussein’s government scrutinized foreign journalists carefully by monitoring all stories and photographs being transmitted out of the country. A lot of photographers were subsequently kicked out of Iraq because the government didn’t like the pictures they saw on the photographers’ digital cameras and laptop screens. Boulat, on the other hand, was shooting film—making it more difficult for the Iraqis to know what she was photographing. She knew this, was allowed to stay, and took advantage of it by traveling all over Iraq.

Just before the American bombs began to fall, National Geographic editor-in-chief Bill Allen called Boulat and suggested that she leave for her own safety. She would have none of it. As other journalists left the country, she hunkered down in a central Baghdad hotel and watched the bombs from her balcony.

In her notes she wrote:

“Third day of bombing. Jet fighters started flying over our heads dropping their missiles over the presidential palace buildings across the river from our quarters at the Palestine Hotel. The power of the explosions was striking. Every minute the sky lit up with a new explosion. The bombing was bearable so I decided to keep my position on the 17th floor of the Palestine Hotel and not to rush down to the shelter. The strike ended after 30 minutes and left dramatic smoke in the air. Buildings inside the palace complex continued to burn all night long and few explosions could be heard from far away.”

Her images of Baghdad before, during, and after the siege remain a unique view of the invasion that few other journalists witnessed.

Legendary photographer Eugene Smith wrote: “To have his photographs live on in history, past their important but short lifespan in a publication, is the final desire of nearly every photographer-artist who works in journalism.” Boulat’s photographs live on in history, hopefully inspiring school girls, as well as young photographers, everywhere.

Read more remembrances of Alexandra Boulat, and learn about the Pierre and Alexandra Boulat Association here.