Revealing America’s brutal new firestorms

Scientists say that the fires ravaging the western United States are burning differently these days. Documenting the aftermath requires a new approach as well.

Today’s fires are different. Blazes have scarred and scorched the western United States for ages, but for scientists who study extreme climate events, like Daniel Swain, the wildfires are now defying historic precedent, moving and growing with a devastating intensity. As Swain, a researcher at University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, puts it, these new fires are doing “seemingly impossible things.”

Take Northern California’s 2020 “gigafire,” the first in the state’s modern fire-tracking history to burn more than a million acres, a footprint larger than Rhode Island. Its size wasn’t unprecedented. The speed of the destruction was. “Two hundred years ago, you probably would have seen million-acre fires, sometimes in California,” Swain says. “They wouldn’t have burned a million acres in a few days. It would have taken months.”

(Inside California’s race to contain its devastating wildfires in 2020.)

More recently, Swain was monitoring the 2024 Bridge fire, raging north of Los Angeles, via satellite thermal imagery. On his screen he could see black splotches on a map that indicated areas burning at temperatures upwards of several hundred degrees—temperatures so hot that “you’re either looking at a volcanic eruption or a wildfire.”

In just its second day, the fire expanded like an ink stain through cotton, running across 45,000 acres, about 70 square miles. That burn rate isn’t unheard of; it occurs with grass fires racing over flat plains. But this was burning forest in some of the steepest mountains of North America. The fire, Swain says, “had to burn up Mount Baldy and down Mount Baldy. And then up the next mountain and down the next mountain, and up and down.”

Researchers have been tracking fires with precision from satellites for more than 40 years, just a small slice of time geologically speaking, but the trends they see are clear: Fires are hotter, burning faster, and destroying more property. “Nearly every year for the past decade, there’s been at least one town in California, or a large part of town, completely decimated by wildfire. That didn’t use to happen,” Swain says. “The changes we’re seeing in decades are changes that would take millennia to many millennia to unfold in a more typical geological history context.”

(Wildfires are making their way east—where they could be much deadlier.)

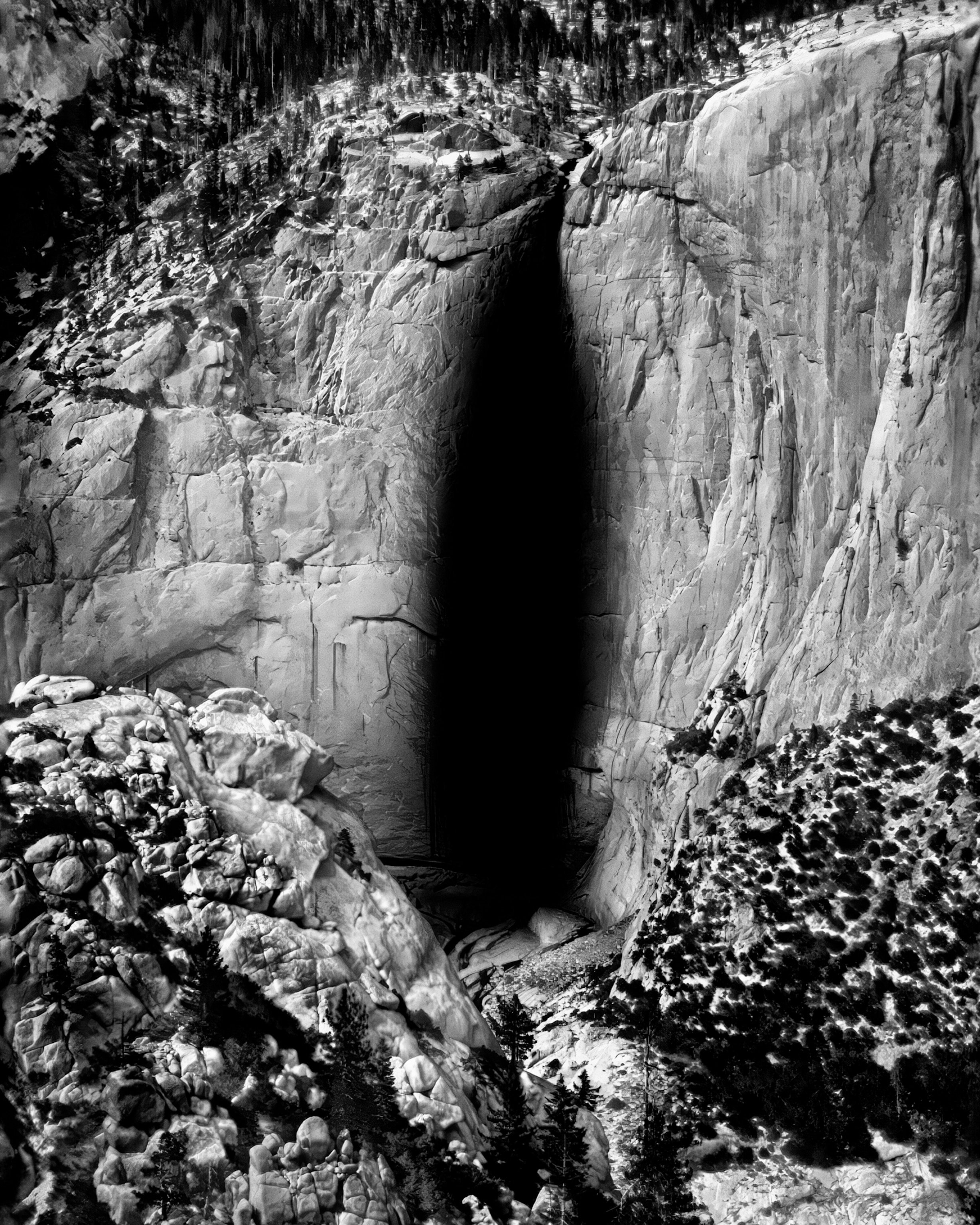

When National Geographic Explorer and photographer Matt Black saw these extraordinary changes happening so close to his home in California’s Sierra Nevada—a 400-plus-mile mountain range that stretches along the interior of the state—he took on the challenge of capturing the aftermath of the fires. But as someone who shoots in black and white, he was concerned about an obvious comparison.

Over the past century, no one has taken such iconic black-and-white images of Sierra Nevada landscapes as Ansel Adams. His work was integral to the modern conservation movement, inspiring generations of people to work together to protect precious wilderness areas. But photographing the landscape in a way reminiscent of Adams “did not feel like it was matching the moment,” Black says. Adams’s images conveyed a postcard-perfect vision of imposing permanence—that such places might stay untouched if we protected them. But climate devastation has destroyed that ideal.

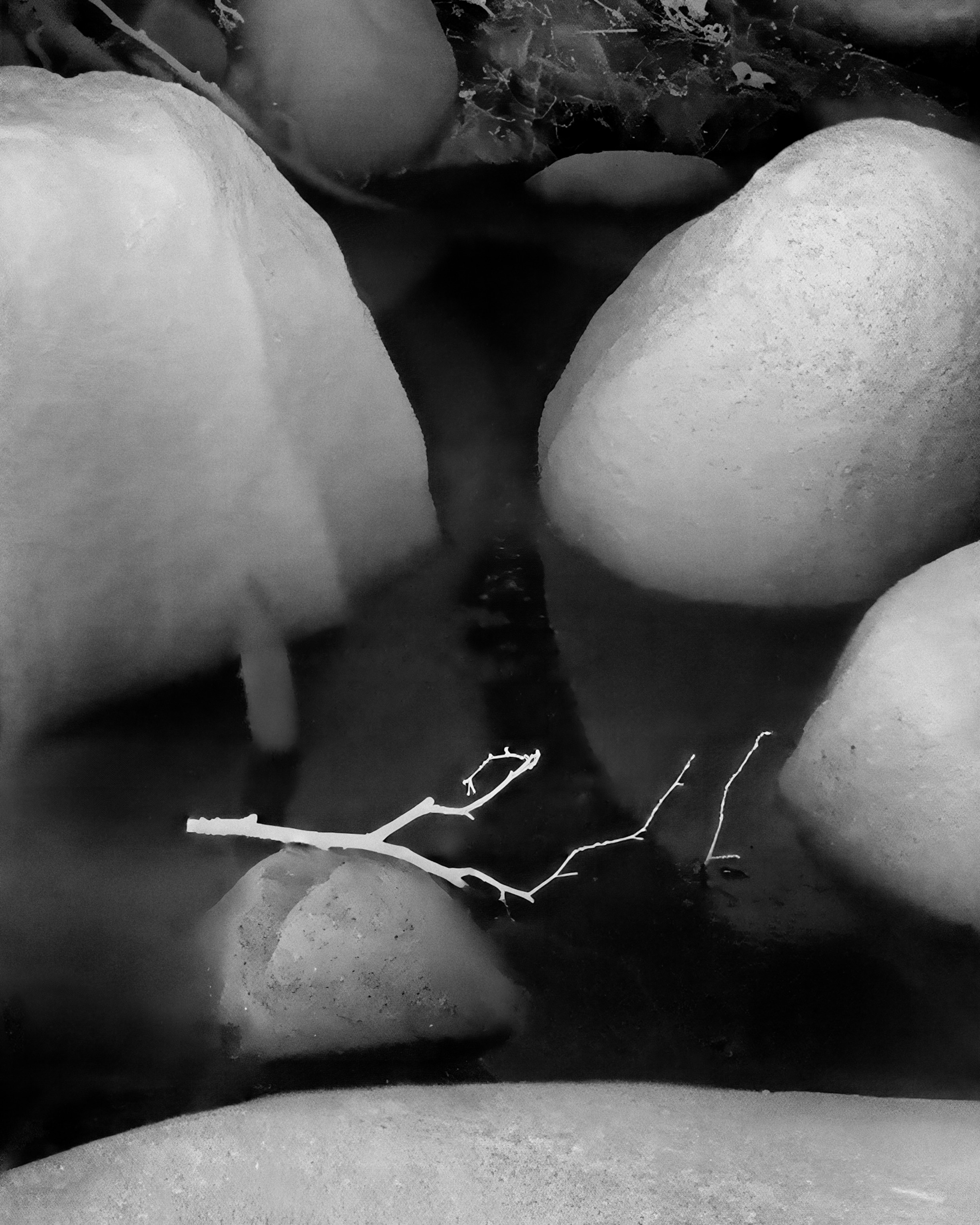

So Black, who was recently honored with a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, turned to an unconventional tool: an industrial thermal camera more typically used to inspect steel forging equipment. While a traditional camera uses light to make images, a thermal camera uses heat. The hottest objects in a thermal image are usually exposed in bright white, the coolest, in inky black.

(Could beavers be the secret to winning the fight against wildfires?)

Beyond its specialized lens and sensor, Black’s handheld camera is fairly conventional. Yet when it’s trained on the natural world, the thermal images it produces are unexpectedly beautiful. But there’s a sinister quality to them too, an ever present reminder of what made them. Our atmosphere is holding more heat than it used to, and some portion of that heat could radiate in each image. “They’re built out of heat that came from elsewhere, that came from the CO2 in the skies above, that came from the exhaust pipes in the cities below,” Black says.

Taking the camera on treks through burned-down forests felt like a revelation. “What was amazing to me was the way it reacted to dead trees,” he says. The charred black trunks trap heat. So “when you look through the thermal camera, they become the brightest points on the landscape.” They appeared alive again, but a ghostly kind of life, shining spectrally among the ruin.

The nonprofit National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded the work of National Geographic Explorer and photographer Matt Black featured in this story. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.