Magical Images Reveal the Beauty and Raw Power of the Ocean

This photographer lives by the tides, the swell, and the wind–championing the natural wonder of our world’s oceans.

Michaela Skovranova jokes that her first underwater photograph was actually made through a glass tank at an aquarium.

While Skovranova was a university student, the Australia-based photographer worked as an education officer at Wildlife Sydney. Her job often required that she work at SEA LIFE Sydney Aquarium, based in the city’s Darling Harbour. On those days, Skovranova would arrive to the aquarium early, at six or seven in the morning, and wander around with her camera. “I wondered what it would be like to swim with the animals and to document them,” she says.

Her favorite animals to photograph at the aquarium were the fur seals. She recalls how engaged they were with her, staring back when she’d look at them through the glass. She’d watch as they played with one another in the water. As soon she’d walk away, she’d notice they would stop.

“They really connected to [me], and I connected to them,” Skovranova says.

Skovranova moved to Australia from Slovakia, a landlocked country in Europe, when she was 13. She wasn’t a strong swimmer—she still isn’t, she says modestly—and at first she was scared of the ocean. The currents were strong, and she didn’t know how to navigate the waves. But she developed a deep affinity for the water, a lifelong affair made stronger by her curiosity and creativity—and her camera.

“I fell in love with the ocean because I feel much more present when I’m in the water,” Skovranova says. “There’s a feeling of weightlessness and a certain level of sound and sensory deprivation that I feel. When I’m in the ocean, nothing else exists.”

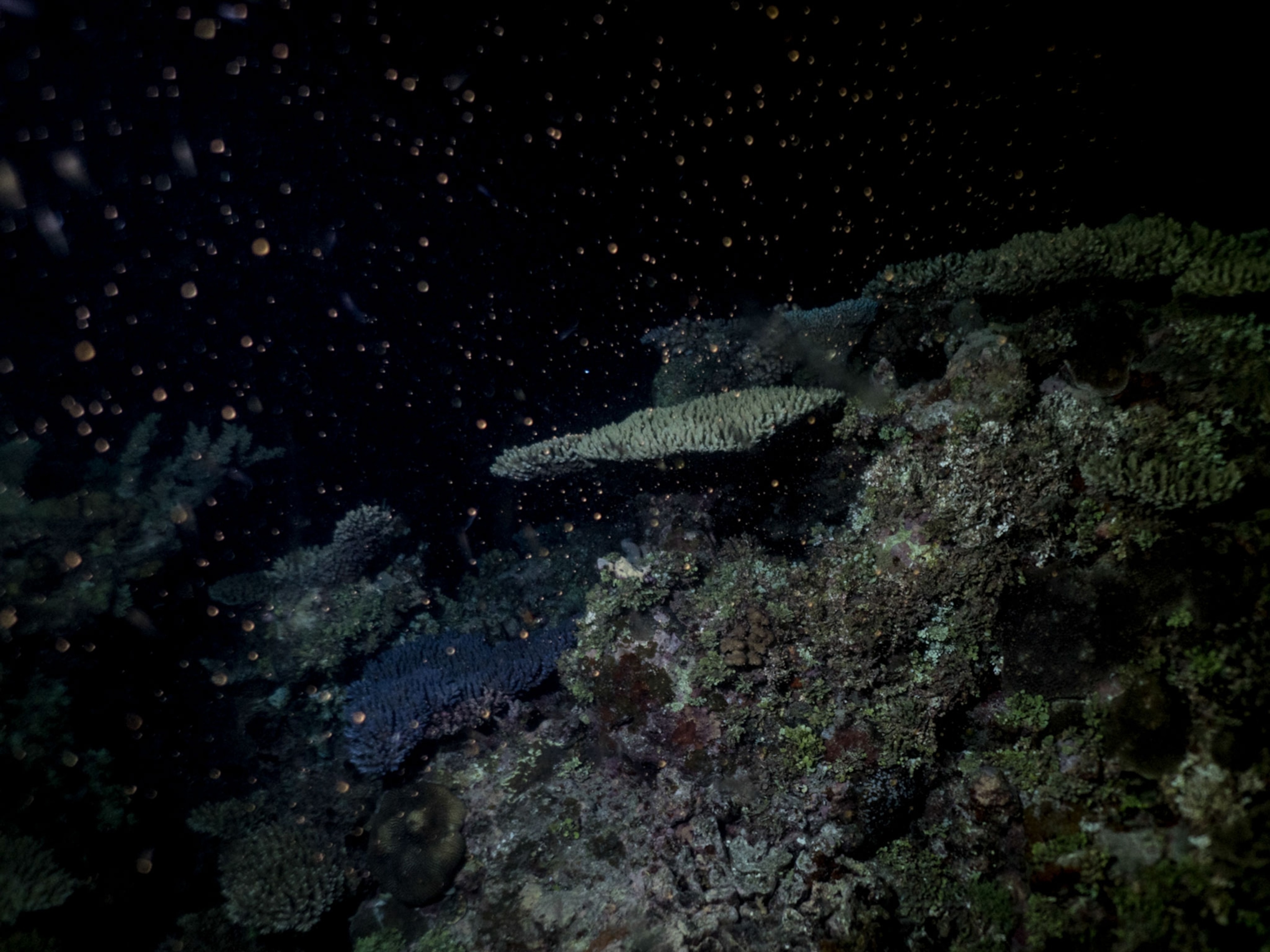

It was in 2014 when Skovranova took a big step in her relationship with the water by jumping into underwater photography. Since then, she has traveled across Australia, Tonga, and Antarctica documenting life just below the ocean’s surface, and she uses as little equipment as possible to do so. Though she has her scuba certification, Skovranova prefers free diving, or what she also calls breath-hold—being in or under water while holding one’s breath. Because of the wildlife she documents and the depths at which she works, Skovranova says breath-hold is a “natural addition” to her process; it allows the surrounding elements to guide and influence her.

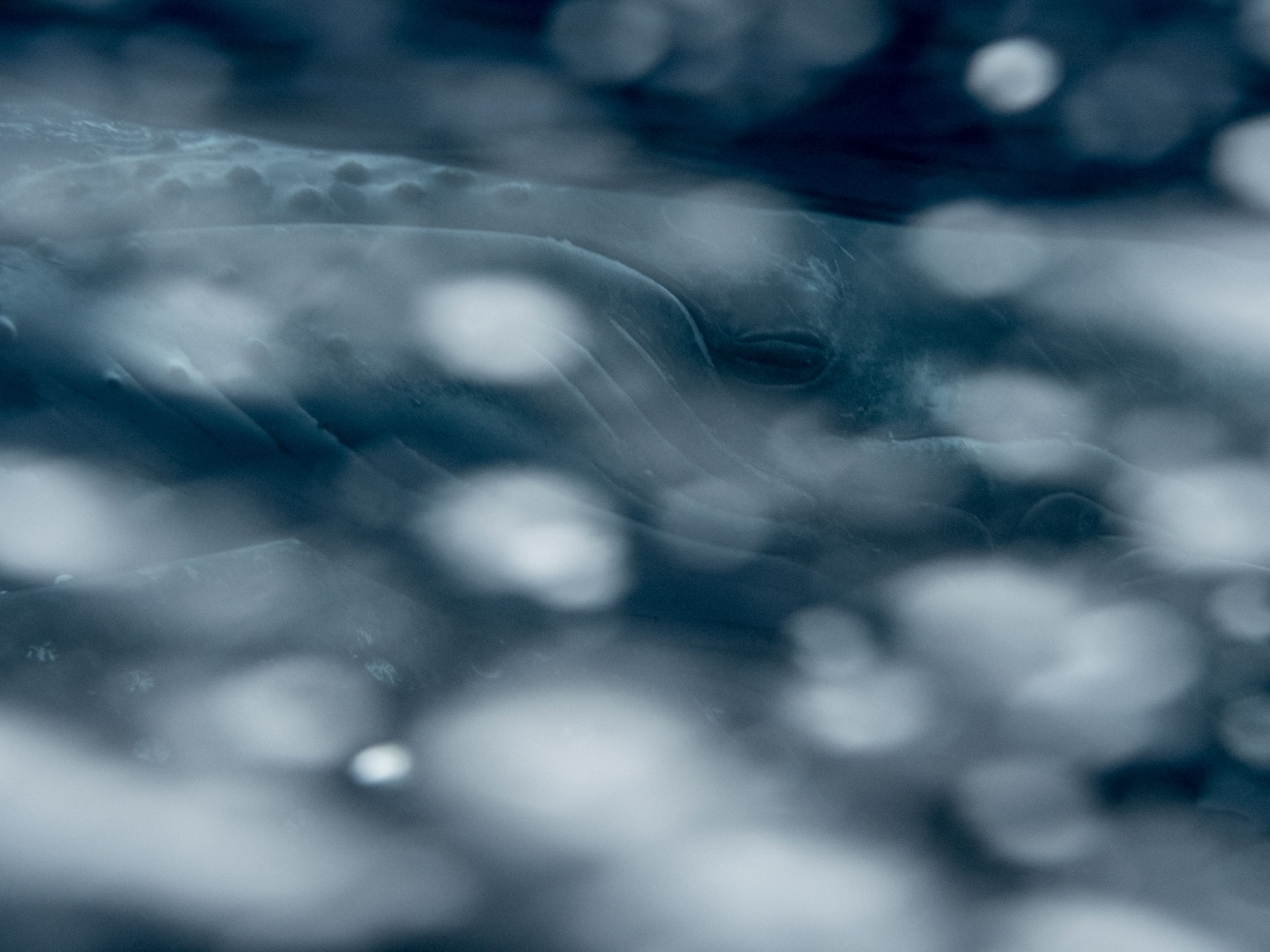

“I love to collaborate with nature,” Skovranova explains. She concentrates on shallow waters, staying within the first 30 feet from the surface and channeling what natural light is available instead of using strobe lighting. Staying closer to the surface also makes much of what she documents—whales and sea lions included—more accessible for people to experience. “You can truly see how complex these creatures are: they talk to each other, they love, they cry, and they sing, just like we do,” she says.

Still, she likes to leave a little bit to the imagination.

“I don’t want to show everything, and I don’t want the images to be too clean or too perfect,” Skovranova explains. “I want all the specks of light and plankton and everything that mixes in the water to be there to really show how much it changes day to day or hour by hour.”

She also hopes her photos demonstrate how special our relationship is to the water, particularly to those for whom the ocean is “out of sight, out of mind.”

“I would love for people far away to feel the presence of the ocean—to feel every drop—and to really create their own connections,” Skovranova says.