Episode 6: Rooting

Tara meets the living descendants of the Africans aboard the Clotilda, the last known ship from the transatlantic slave trade to reach the United States. They inspire Tara to look into her own family’s past in her hometown, where she makes some surprising discoveries.

National Geographic Explorer Tara Roberts is inspired by the stories of the Clotilda, a ship that illegally arrived in Mobile, Alabama, in 1860, and of Africatown, created by those on the vessel—a community that still exists today. The archaeologists and divers leading the search for Clotilda lay out the steps it took to find it. As Tara talks to the living descendants of those aboard the ship, she admires their enormous pride in knowing their ancestry, and wonders if she can trace her own ancestors back to a ship. She hires a genealogist and visits her family’s small hometown in North Carolina. The surprising results bring a sense of belonging to a place that she never could have imagined.

Listen on iHeartRadio, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Castbox, Google Podcasts, and Amazon Music.

TRANSCRIPT

LULA ROBERTS (HOST’S MOTHER): Cute little car.

TARA ROBERTS (HOST): Yeah, it’s really little.

LULA ROBERTS: Drive carefully.

ROBERTS: I’ll be fine, Mom.

LULA ROBERTS: Get that child to do your nails.

ROBERTS: Yeah, my toenails are not looking so good.

LULA ROBERTS: Give me a call now.

ROBERTS: Mom, please don’t call me 10 times.

Oh! I need the keys to the house.

Yep, Sunday evening.

LULA ROBERTS: All right, my dear, let’s get a good hug. God bless.

ROBERTS: I’m off to Edenton, North Carolina, the town where my mom grew up, to visit her family estate. That sounds super grand, doesn’t it? The family estate. It’s really just the house and land where she was born.

When I used to visit my grandmother as a kid, my impression of the place was miles and miles of cornfields, lazy quiet, only the droning of bees and singing of crickets to break up the monotony of the day.

I felt the oppressive weight of the silent country resting upon my shoulders back then.

But now, I wonder if there was something in this place for me. Something necessary and strong that could also help ground and root me.

In the last episode, we talked about collective trauma and the power of ritual and ceremony to heal. We also saw how healing can come from a direct connection to the ancestors on these ships.

In this episode, we’ll get even more specific and explore what kind of difference knowing your particular ancestry makes.

I heard about this unique community right here in the U.S., in a place called Africatown, located in Mobile, Alabama.

Many of the people who live there know that they have ancestors who were brought over on the Clotilda, a ship that trafficked humans during the transatlantic slave trade.

And so I wanted to know more. Plus, I wondered if I could go as deep into my own history.

Could I also trace my ancestors all the way back to a slave ship? And does it matter if I can?

KAMAU SADIKI (DIVER): If you’re not connected to your ancestors, it’s like you’re always gonna be wandering, lost, misguided, not knowing what direction you should be taking.

ROBERTS: This is our last episode, y’all. And we’re headed back Into the Depths to bring it all home.

That is, right after the break.

ROBERTS: My trip to North Carolina was inspired by the people who came over on the Clotilda.

The Clotilda is the last known ship that brought captive Africans over to the United States, to Mobile, Alabama. And the incredible thing about the Clotilda is that some of the people who live in the area now, in Africatown, actually descend from those original captured Africans who were on that ship.

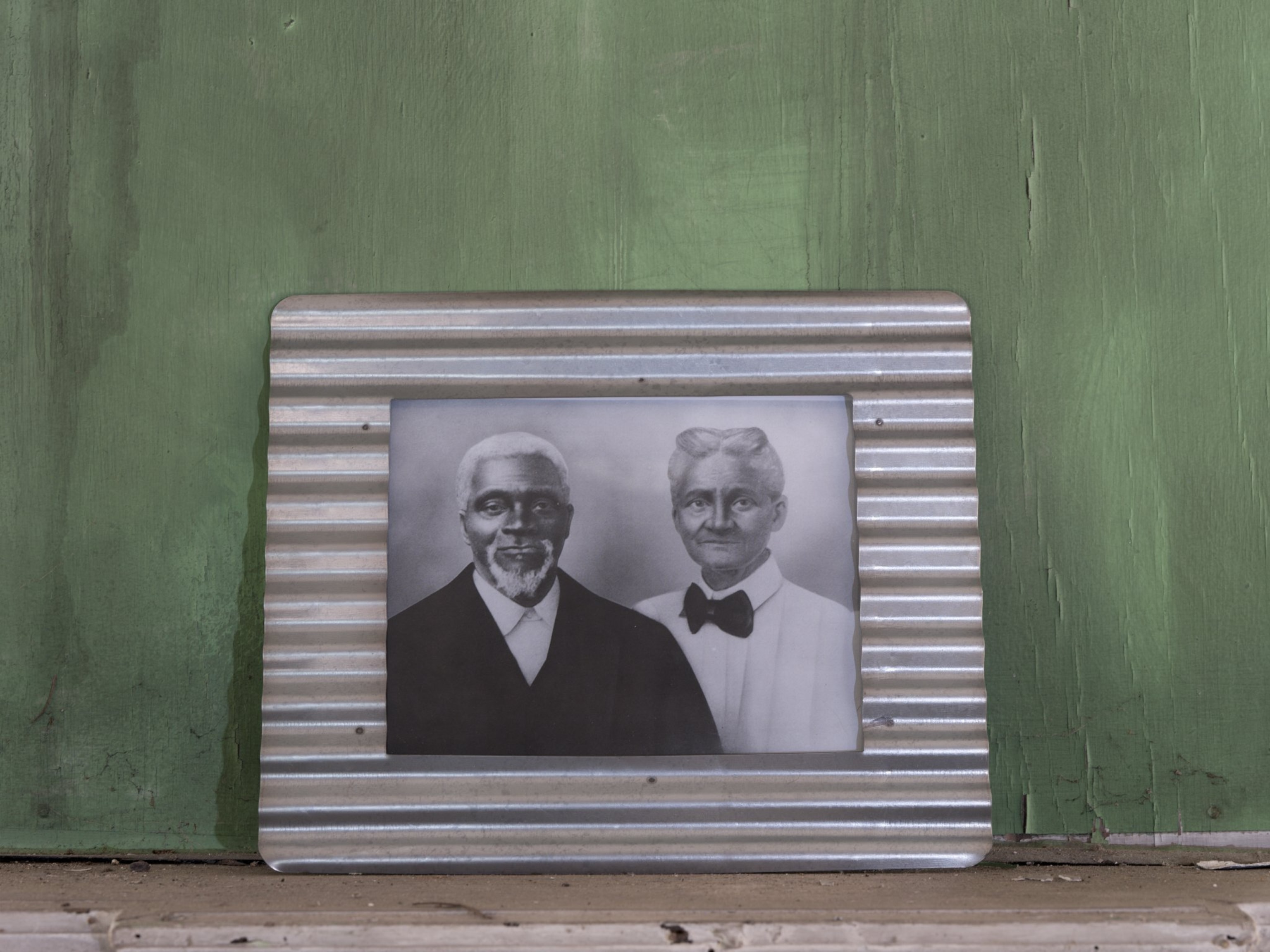

These residents know the names of their ancestors. They know their stories. There is a direct connection.

I had been to Africatown a few months earlier to meet them.

JOYCELYN DAVIS: My name is Joycelyn Davis.

JEREMY ELLIS: My name is Jeremy Ellis. And I am a fifth-generation descendant of …

DAVIS: I’m a direct descendant of …

ELLIS: … Pollee Allen and Rose Allen

DAVIS: … Charlie Lewis and Maggie Lewis

ELLIS: Who were …

ELLIS/DAVIS: … two of the enslaved Africans brought over on the slave ship Clotilda.

ROBERTS: And say just a little more about who Pollee and Rose are, exactly, what you know about them.

ELLIS: Rose Allen, she was one of the enslaved Africans on the ship. She was the first wife of Pollee Allen.

So we know that he was a reverend. We know that he, when he was enslaved, worked on the steamboat. That is how he found out about his freedom.

He was a gardener. He grew onions and garlic and plums and apples. And also he was a carpenter. He built his house.

ROBERTS: The descendants grew up hearing the stories of how their family had reached Alabama from what is present-day Benin and Nigeria.

DAVIS: Growing up, I heard about this story of Timothy Meaher making a bet.

ROBERTS: It was 1859, and the transatlantic slave trade had been abolished by countries around the world. A plantation owner and shipbuilder in Mobile, Alabama, named Timothy Meaher, had heard that West African tribes were at war, and that King Glele of the kingdom of Dahomey, in what is now modern-day Benin, was willing to sell enemy prisoners to be enslaved.

DAVIS: I heard that they came from different villages, and they wanted to make sure that they spoke different languages, so they wouldn’t communicate with one another. So that was, I was like, Wow. So it was a carefully thought-out plan.

ROBERTS: Meaher’s friend and partner Captain William Foster sailed there to purchase the local prisoners.

ELLIS: He was there for about nine days, where he would go down into the barracoon, and he would literally select Africans. What we know is that for every man, he would look to select a female, a woman, to go. And so, $9,000, plus some gold and silver, he purchased about 125 slaves.

ROBERTS: Only 110 made it onto the Clotilda. One was Kossola, later given the enslaved name Cudjo. We met him in episode four. He was interviewed starting in 1927 by writer, anthropologist, and one of my personal sheroes Zora Neale Hurston. I actually named my cat after her.

The book Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” based on those interviews with him, was published recently.

Kossola shared a firsthand account of the voyage as a captive.

KOSSOLA (FROM BARRACOON, AS READ BY JOSHUA C. THOMAS): De boat we on called de Clotilde. Cudjo suffer so in dat ship. Oh Lor’ I so skeered on de sea! De water, you unnerstand me, it makee so much noise! It growl lak de thousand beastes in de bush. De wind got so much voice on de water.

ELLIS: And they were actually under, in the bottom of the Clotilda. So it was a very brutal trip for them.

KOSSOLA (FROM BARRACOON, AS READ BY THOMAS): Soon we git in de ship dey make us lay down in de dark. We stay dere 13 days. Dey doan give us much to eat. Me so thirst! Dey give us a little bit of water twice a day. Oh Lor’, Lor’, we so thirst! De water taste sour.

ELLIS: What we do know is that they arrived July 8, and they actually avoided customs. They knew that what they were doing was illegal.

ROBERTS: The ship arrived in the middle of the night. And after those on board were taken off and hidden in the swamp at the edge of the river, Captain Foster needed to hide the evidence. He set the ship on fire and sank it in the muddy Mobile River.

KOSSOLA (FROM BARRACOON, AS READ BY THOMAS): First, dey ’vide us wid some clothes, den dey keer us up de Alabama River and hide us in the swamp. But de mosquitoes dey so bad dey ’bout to eat us up, so they took us to Cap’n Burns Meaher’s place and ’vide us up.

ROBERTS: The group was then dispersed, distributed to the financial backers of the Clotilda, with Timothy Meaher keeping 32 of the captured people.

The punishment for this illegal act? Next to nothing. Maybe because of the close ties the Meahers had with the city government.

So with the kind of money and power he had, it was easy to take these kinds of risks.

Then came the Civil War. And in 1865, five years after reaching Alabama, the people who came over on the Clotilda were free.

Their first wish? To return to Africa. But they didn’t have enough money to buy passage. So the community decided to pool their earnings and purchase 57 acres of land. It probably cost around $300.

With it, they formed their own version of home and called it Africatown, incorporating their agricultural knowledge and folk traditions.

And Africatown took off.

The residents built three dozen houses, a church, a school. They even had their own graveyard.

ELLIS: That’s a 14-year time frame, essentially. Out of those 14 years, only nine of those years they were free. And they had the brilliance and the intellect and the passion and the wherewithal to do all of those things.

I look back and I even try to reflect over, What did I do in 10 years? If that doesn’t motivate you or get you excited, understanding that that DNA resides in you, then I don’t know what will.

ROBERTS: More after the break.

(Siri virtual assistant announcing, “Continue on I-85 North for 35 miles … Welcome to North Carolina.)

ROBERTS: So I’m here. I made it to the house. And I am parked, and Joseph Beasley, the guy who cuts our grass, is coming. But I’m just sitting here and looking at the property.

ROBERTS: Do you know if that’s our land? If that’s my grandfather’s land?

JOSEPH BEASLEY (GARDENER): Well …

ROBERTS: You’re not sure?

BEASLEY: No, I’m not sure because all the way back to the—it’s another path where you can come in and go down … and I’mma finish taking care of this grass here.

ROBERTS: OK!

I made it to my mom’s childhood home. My grandparents’ house in Edenton, in Chowan County, North Carolina.

It was actually a big house: two stories, with a porch and columns. But it was in a state. There was a big hole in the sidewall. A hole I could actually bend my leg, stoop down, and walk through. Most of the ceiling in the kitchen had fallen down. There was plaster, debris everywhere, even visible mold on the walls. The windows had all been broken, and there was glass below them.

I don’t know why this just dawned on me, but my grandfather, who only had a fourth-grade education, managed to buy a former plantation with around a hundred acres of land back in the 1930s.

How could I have not understood the significance of this growing up?

I think it was learning the story of Africatown and understanding the legacy of that land that put this acquisition in a new light. It made me realize I’d probably missed more about my family’s legacy. Plus, I’d never really thought to see how far back I could go.

I decided to hire a genealogist to help me go back further and deeper.

RENATE YARBOROUGH SANDERS (GENEALOGIST): Can you hear me?

ROBERTS: Renate Yarborough Sanders specializes in African-ancestor genealogy.

So do you think that I can find the ship that my ancestors came over on?

SANDERS: (Giggle) I never say never, but it is—it’s something that not very many people have been able to do.

ROBERTS: Renate explained that the problematic date in the research is 1870.

SANDERS: That’s when you get to that fork on the road.

ROBERTS: Many people call it the 1870 brick wall, because before it, enslaved African Americans were not officially documented by name, age, gender, or otherwise.

Renate said she’d see what she could find out about my great-great-grandpa Jack, who was born in 1837.

ROBERTS: Is there anything that maybe I didn’t ask that comes to mind?

SANDERS: Just a reminder for you to be patient and to not really get your hopes up, because it’s going to be tough, very tough, to find those generations before him that will take us back to a slave ship. And so, as I mentioned to you, that’s not a really … I don’t ever like to say it’s never gonna happen, but it’s not realistic.

ROBERTS: I may not be able to find the specific ship, but it feels good to be looking.

The residents of Africatown didn’t have to do this particular kind of searching.

There’d always been rumors and folklore in Africatown around where the wreck of the Clotilda was located. It was known that when the ship reached Mobile, William Foster had wanted to hide the evidence.

JIM DELGADO (HISTORIAN): And there he says, “I burnt and sank my schooner in 20 feet of water.”

ROBERTS: Jim Delgado is the historian and maritime archaeologist who has been at the helm of the mission to find the ship. Fred Hiebert, the archaeologist in residence at the National Geographic Society, helped with the search, along with DWP lead instructor Kamau Sadiki. You met him in the last episode.

SADIKI: There’s always—the people in the community had always asked the question, We need to find the ship. We need to find the ship. And I guess in a sense, they knew how important it was to find a tangible artifact that got them where they are to help tell their story. But I think it was back in January of 2018, due to some meteorological conditions in the region, the water level of the Mobile River dropped, and it exposed this old wooden vessel, possibly the Clotilda.

DELGADO: And then crusading environmental reporter Ben Raines went and figured out that there likely was a ship there.

FRED HIEBERT (ARCHAEOLOGIST): Had come to a pretty good idea of which stretch of the river it was.

DELGADO: So we …

ROBERTS: Jim Delgado’s company Search, along with the National Park Service, the Slave Wrecks Project, Diving With a Purpose, and with support from National Geographic …

DELGADO: We all reached out and offered to help. We all went out there, working with the Alabama Historical Commission, who were the stewards of all of the history and archaeology. We met out in March …

ROBERTS: 2018.

DELGADO: We went. We mapped. We measured.

SADIKI: … and came to the conclusion very quickly that this vessel was too big, too broad, based on the measurements we knew of the Clotilda. We know it had a depth of all about seven feet, the length of almost 88 feet, and the breadth was about 23 feet or so.

So, when we did the quick dimensions of this earlier ship, we know that it was over a hundred feet long. So we knew right off that it wasn’t, but an interesting vessel nonetheless.

ROBERTS: The local community, though, had gotten excited. So the following year, Jim, his team, Fred, and Kamau went out again. To a different part of the river, which their research showed was a more likely spot. And they started the search again.

DELGADO: We went back twice. Systematically mowed the lawn with sonar, with magnetometers that detect buried masses of metal that exerted magnetic influence.

HIEBERT: We’re out there on this iron barge, towing this sonar behind us, making a beautiful map of the bottom.

Tara, it was so hot. It’s like there’s no shade, there’s just—I mean it’s 120 degrees. It, you know, people come … we had people who were fishing, who came by and they kind of laughed at us and said, like, you know, “It’s so hot, even alligators aren’t out!”

ROBERTS: They found hundreds of anomalies. It turned out the area was a ship’s graveyard. Meaning wreckage and debris from many ships.

DELGADO: One target stands out, though. It’s the right size, but sonar records alone aren’t good enough. It really needs to be systematically looked at.

We have to dive and look at everything.

SADIKI: So it’s a very dangerous sort of environment, simply because the wreck is in a condition that it’s in. It could actually collapse at any point.

ROBERTS: The search team needed to put a technical diver into the water.

(Underwater communication saying, “OK, the diver’s got an all-wood hull …”)

SADIKI: So when he got into water, he immediately said, “I can’t see a thing.” And so he started feeling his way around. And then he came upon this wooden vessel.

(Underwater communication saying, “All right, the diver’s got an all-wood hull, reaching over six to seven feet above.” A walkie-talkie responds an indecipherable message. Diver replies, “Correct.”)

SADIKI: And we all could hear the communications on the boat, right? And so that’s when things have sort of gotten real tense. What is he going to say?

(Underwater communication saying, “Over six to seven feet above …” Walkie-talkie responds.)

SADIKI: He said, “I feel something here. It feels as if it’s a bow; I’m running my hands up, it’s over my top of my head, and I can feel it.”

Put another diver in the water. Came back with some samples, some very small samples because we don’t want to destroy anything. It was evidence. There was enough material to analyze the wood.

DELGADO: So with that, we were able to then announce that we had identified this wreck as the likely Clotilda.

It’s a time capsule of sorts that has been cracked open.

And in that, I will just say this simply: When you are in that space, and you see how small it is, very tangibly, physically, viscerally, gives you a glimpse of just what happened here.

It’s a very sobering and terrible place to be, and yet it serves as tangible, physical evidence. Not only of the crime that was done, but of the ability of this site to continue to help tell this story.

ROBERTS: Back in Edenton, I went looking for my own history.

Edenton totally charmed me this go-round. Big porches. The pier downtown. Friendly folks who wave at you from across the street. And as it turns out, my family’s hometown has a surprising connection to an enslaved woman who had escaped bondage using a network I’d never heard of.

Outside the Historic Edenton State Historic Site, I found a plaque. It had on it the name Harriet Jacobs. When I met with the local historian, Charles Boyette, he told me an incredible story.

CHARLES BOYETTE (HISTORIAN): She essentially hid out in her grandmother’s attic for about almost seven years before she was able to escape on a ship dressed as a sailor on the Maritime Underground Railroad.

ROBERTS: Wait. Rewind. What? The Maritime Underground Railroad?

BOYETTE: The Maritime Underground Railroad was the hidden network of connections and safe houses that allowed enslaved persons to seek their freedom along the waterways. The waterways were the major arteries of trade back then before, you know, paved highways. And a very large portion of the sailors, dockworkers, fishermen, just people who made their living off the water and waterfront were African American, either free or enslaved.

ROBERTS: Harriet Jacobs went on to write about her experiences being enslaved and escaping from slavery in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1861.

HARRIET JACOBS (AS READ BY POET ALYEA PIERCE): When I entered the vessel, the captain came forward to meet me. He was an elderly man, with a pleasant countenance. He showed me to a little box of a cabin.

ROBERTS: Her account was one of the few known narratives of the enslaved. That’s where these excerpts come from.

JACOBS (AS READ BY PIERCE): The vessel was soon under way, but we made slow progress. Until there were miles of water between us and our enemies, we were filled with constant apprehensions that the constables would come on board. Neither could I feel quite at ease with the captain and his men. I was an entire stranger to that class of people, and I had heard that sailors were rough, and sometimes cruel. We were so completely in their power, that if they were bad men, our situation would be dreadful.

Now that the captain was paid for our passage, might he not be tempted to make more money by giving us to those who claimed us as property? I was naturally of a confiding disposition, but slavery had made me suspicious of everybody.

ROBERTS: Harriet’s story wasn’t a one-off, by the way. The Maritime Underground Railroad operated for years, leveraging the shipping routes that were already delivering goods from the south to the north.

BOYETTE: We have a marker down here on our waterfront. We have a picture of the type of boat she probably was able to escape in.

ROBERTS: Whoa, this is just a wooden boat. It’s like a rowboat.

BOYETTE: Yes, she would have got to the ship on that. They would have rowed her to the ship. Then it was on a regular ship.

JACOBS (AS READ BY PIERCE): Ten days after we left land, we were approaching Philadelphia. I was on deck as soon as the day dawned … to see the sunrise, for the first time in our lives, on free soil; We watched the reddening sky and saw the great orb come up slowly out of the water.

ROBERTS: I had never heard about either the Maritime Underground Railroad or Harriet Jacobs when I was at school. Or the Clotilda either.

Harriet could have been my role model as a kid. She was from my family’s hometown. And I was destined for maritime exploration.

Perhaps I would have felt the same sense of pride for her that the descendants of the Clotilda felt for their ancestors.

SADIKI: I think Clotilda should be particularly U.S. history, if not world history. It has a specific role to play.

If we’re not aware of these stories, you know, we’re just going to go along merrily. And then all of a sudden, these stories pops up. And people start asking questions. What? Why? Why wasn’t I told this? Why wasn’t I aware of this?

So in order for us to go forward for a sense of justice, a sense of honesty, being candid with each other, we have to tell the whole story.

ROBERTS: Renate sent me an email. She had some results.

She told me that Jack was indeed enslaved, and that she had managed to find out who one of the enslavers was. A guy called James L. Roberts. I guess we get our name from him.

She hadn’t found a ship, but she had found out other things about my great-great-grandpa Jack.

First, he had land. A lot of land. At least 174 acres in total. Renate showed me the deeds outlining the boundaries of the land he left to my great-grandpa.

SANDERS: Allotted to J.H. Roberts, beginning at a ditch on the road, middle of swamp. Thence up middle of swamp to a point …

ROBERTS: Second, Jack was a chosen delegate to the 1865 Freedmen’s Convention in North Carolina to discuss constitutional rights for freed slaves.

Finally, there was evidence that Jack fought in the Civil War, in the United States Colored Troops. Second Regiment, Company B.

SANDERS: If that’s your ancestor, it is a huge, big deal.

ROBERTS: Not only does this bring up feelings of pride for me about Jack and my family, but it makes him feel like a real human being.

SADIKI: I can trace my ancestry back to my great-great-grandparents.

ROBERTS: Kamau goes back about the same as me. But he sees his ancestry in the Clotilda, even though his family didn’t come over on that ship.

SADIKI: I see my story as part of the Clotilda story as well.

You know, I knew enough about history to know that we are connected in that way. So we have very similar stories to tell, you know, and our cultural experiences have been very, very similar too.

You know, the whole discussion of race, people find it very sensitive to talk about that, when it’s the bedrock of why we are where we are right now. So we should have open dialogue and discussion, honest discussions, about, you know, can we get to the point where we can treat each other as an individual, individual human beings?

And so, if we don’t tell the Clotilda story, I don’t think we’ll be able to get there. Because the Clotilda story plays, and these other slave vessels, in the whole history of race and the efforts of white supremacy and the deconstruction of reconstruction, you know, how it plays into getting us where we are now.

(Mosquitoes buzzing)

ROBERTS: These mosquitoes are insane.

(Car door clicking open)

Like literally the mosquitoes.

HIEBERT: Yeah. I mean …

ROBERTS: Fred—

(Woman’s voice talking nearby)

ROBERTS: Do you—the mosquitoes. Look at this.

(Car door slamming shut)

It’s like 10 of them in here.

HIEBERT: Oh, OK. All right.

ROBERTS: This is gonna kill me. Ah!

HIEBERT: All right.

ROBERTS: Do you want to get in the car?!

HIEBERT: Yeah. (Laughs)

(Car door opening, then shutting)

ROBERTS: Fred and I had gone to visit the house that Kossola, of the book Barracoon, built and lived in. But when we got there, we found a literal swarm of mosquitoes. Perhaps greeted not that differently than Kossola had been when he reached Mobile over 160 years ago.

KOSSOLA (FROM BARRACOON, AS READ BY THOMAS): The mosquitoes, they so bad, they ’bout to eat us up.

ROBERTS: Joycelyn said she’d never seen anything like this before.

(Car door opening)

HIEBERT: You know where it is, right?

(Car door shutting)

ROBERTS: Ah! Yes. Shit. He just let in like 10 mosquitoes.

HIEBERT: Argh.

(Mosquitoes buzzing)

Had to be thousands of mosquitoes that suddenly appeared from nowhere. Diving, bombing, biting, filling my car, because Fred wouldn’t close the door fast enough!

I wondered if the ancestors were speaking to us that day, trying to get our attention.

(Sounds of people on the street, dogs barking)

ROBERTS: Again, I couldn’t have planned this if I tried. But I ended up in Edenton during the first ever national Juneteenth celebration.

June 19, 1865, was the day that enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, got the news that they were free.

In Africatown, Jeremy’s great-great-great-grandfather was on the steamship working. Here in Edenton, North Carolina, who knows where my great-great-grandpa Jack was that day. I like to think of him running home to hug his wife, Mary. Spending their evening planning their future.

And there I was in Edenton, experiencing the new national holiday in a place bursting with family.

CAROL ANTHONY (EDENTON RESIDENT): I just love Edenton. I’m connected to the Roberts family through marriage. I’ve married into the Roberts family.

ROBERTS: And can we note that, like, we’ve never met before, and you’re just passing by, and I’m like, “the Roberts,” then you’re like, “Wait? Which Roberts?” Like, that’s crazy.

So, say what the connection is exactly.

ANTHONY: Well, Teeny is your uncle, right? And I’m married to his stepson.

ROBERTS: I’m not going to go into the details of Uncle Teeny here, except to say he’s my cousin Karen’s father. She’s the one from the first episode who started doing all this family research in the first place. Kismet!

The point here is that in downtown Edenton I kept running into people who were family or who knew my family, and it made me feel great!

That evening there was a vigil. They lit a candle to get rid of the negative energy of plantation culture, and citronella to dispel it. And then they topped it off with sage to bring in positive vibrations.

I’ve spent my life thinking that this area was boring, and that Black people were disregarded, at the bottom of the heap. It depressed me coming here.

But I did a full 180. I started calling realtors about buying property in town.

As I sat on the porch of my B&B on Broad Street, feeling the breeze, I thought about what I had learned so far.

The necessity of telling this history. Of who tells this history. Of involving the community as framers of this history.

I thought about this new idea of a global Blackness not based on geography, that is emerging in my mind. I am, we are, more than something created as a juxtaposition against something else.

I thought about the power of ritual around these ships to heal our collective past trauma.

And this connection to the ancestors, to seeing glimpses of their full lives and stories, that can make us feel pride.

I felt more grounded.

This journey following Diving With a Purpose, of learning about the ships and of digging into my past has given me a new sense of pride. It’s helped me see threads of resistance and rebellion. And I see that we actually have healed some of this trauma as a community.

We’re not at the start of this process.

Some of you have known this all along. People like Kamau. People like Karen. Like Lonnie. Maybe even like you. I was late to the party. But I’m so glad I finally accepted the invitation.

Since great-great-grandpa Jack was born in 1837, it’s possible that I am only a generation away from finding a ship and a direct route back to the African continent. To knowing my whole story. Or at least the fullness of these particular chapters.

I needed to check in with my girl Karima. I wanted to ask her what she thinks about where I am now.

ROBERTS: Do you think I’ve changed?

(Sounds of crickets in the background)

KARIMA GRANT ABBOTT (FRIEND): Oh, yeah. Yeah. I think the change is going to be a certain amount of peace. I think you’ve understood and come to that aspect of grace.

All migration or movements or journeys aren’t all traumatizing. They actually are creating and reforming and rebuilding, and you know it’s adaptive too.

ROBERTS: But where do we go from here around the search for more shipwrecks?

Only a few wrecks have been found out of a potential thousand. And these missions cost money.

Organizations like DWP, Ambassadors of the Sea, and others need more divers, more equipment, more resources.

You know Kamau. But do you remember Ken, Ayana, and Justin, DWP divers from earlier episodes? Well, I asked them about their visions for the future.

KEN STEWART (DIVER): DWP’s mission needs to be, obviously maybe finding some more wrecks, but telling the story of the African diaspora and bringing it back to life. And not to undercut it, right, and put it into the background. It needs to be a solid piece of history, taught in the schools.

SADIKI: We do know there’s a number of vessels out there, up and down the eastern seaboard of the U.S., and the Caribbean, and South America, off the coast of Africa. Around islands like St. Helena in the middle of the Atlantic and all these other island nations as well. So we’d like to train individuals, particularly young people, to have the skill sets to do this kind of work.

JUSTIN DUNNAVANT (DIVER): I think it’s critically important that DWP takes a project from beginning to end. DWP has done so much critical work on existing projects; the work they could do on their own projects could be even more powerful and more impactful.

AYANA FLEWELLAN (DIVER): I don’t quite know what that looks like right now, but I know it exists. It sounds cheesy! But it feels free. You know?

ROBERTS: Yeah … and I like it.

LONNIE BUNCH III (HISTORIAN): What I think history does is it teaches you nuance, it teaches you subtlety, it teaches you complexity, it teaches you ambiguity. Imagine what a contribution you make, if all of America could embrace nuance and complexity, rather than simple answers to complex questions.

ROBERTS: The words of Lonnie Bunch III, now secretary of the Smithsonian, still ring in my ears. Lonnie now oversees the 19 museums and 21 libraries of the Smithsonian.

Progress is definitely being made.

ROBERTS: Do you think it matters to know that kind of history, where we came from?

I’m here with my nieces Wu and Shi, trying to be the conduit for them that my ancestors have been for me. We’re learning from each other.

WU (NIECE): I think it matters. I think it’s pretty cool.

ROBERTS: Let me ask you this. Do you know that your ancestors, like way, way, way back, came from Africa?

SHI (NIECE): No.

ROBERTS: Did you know that?

WU: Yes. I did know that. That my ancestors came from Africa.

ROBERTS: Do you guys know about the work I’m doing?

WU: The history of the slave ships and about your family.

ROBERTS: Yeah. I’m following these divers as they search for slave shipwrecks. So what do y’all think about that?

SHI: I think that’s pretty cool. You get to explore more about the world, and you get to learn more stuff that you didn’t already know. And I think that’s cool.

ROBERTS: Do you care about that history? Like, knowing all that far back?

SHI: It’s awesome. It’s cool. Like when you get older, you’ll be able to tell people that you had this cool aunt, and she did all this stuff. And she got to explore the world.

WU: I wish I could do it. But I still got school to finish out, which is boring. ’Cause if I didn’t have school, I would have been joined you on it, of course.

ROBERTS: Will y’all come scuba diving with me one day?

NIECES: Yes, I will. Yes, I will. Yes, I will!

ROBERTS: Yes, you will! This is the new saying. Instead of Obama’s “Yes, I can,” it’s “Yes, we will!”

WU AND SHI: Yes! (Giggling)

ROBERTS: If you loved this podcast, you can dive deeper at natgeo.com/intothedepths, where we’ve got a ton of resources to help you explore this history. You’ll find more on my work with these divers and stunning photos from photographer Wayne Lawrence. And for all our teachers, we have some great tools you can use in your classroom. Also, check out our special in-depth feature in the March issue.

Plus, don’t miss Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship—a film from National Geographic Studios premiering on Hulu in February. You can find all the links in the show notes, right there in your podcast app.

Please rate and review us. And to support more content like this, consider a National Geographic subscription and listen to Overheard, our weekly podcast. That’s the best way to support us and hear more adventures from around the world. Go to natgeo.com/explore to subscribe.

CREDITS

I’m National Geographic Explorer Tara Roberts, host and executive producer.

Into the Depths is a production of National Geographic Partners and is funded in part by the National Geographic Society.

It’s directed by the awesome Francesca Panetta, who got us to the finish line. Thank you!

And produced by the tireless, ever ready Bianca Martin and my ride-or-die Mike Olcott.

Our poet is the brilliant wordsmith, National Geographic Explorer Alyea Pierce.

Our executive editor is Carla Wills.

Our executive producer of audio is Davar Ardalan.

Our fact-checkers are Kate Sinclair and Heidi Schultz.

Our copy editor is Jennifer Vilaga.

Our production assistant is Ezra Lerner.

Our sound designer, engineer, and composer is Alexis “Lex” Adimora.

Our audio engineers are Jerry Busher and Grahame Davies.

Additional reporting was done by Tiffany McNeil.

Thanks to Harper Collins, publisher of Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.”

Joshua C. Thomas was the voice of Kossola.

Special thanks to Helene Pellett.

And our consultants, who offered sharp critiques, insights, and encouraging words when we needed them, are Ramtin Arablouie, John Asante, Greg Carr, Celeste Headlee, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Linda Villarosa.

Debra Adams Simmons is National Geographic’s executive editor of history and culture.

Whitney Johnson is the director of visuals and immersive experiences for National Geographic.

Susan Goldberg is National Geographic’s editorial director.

Thank you to Fleur Paysour, from the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Slave Wrecks Project, for opening doors, literally.

To MIT Open Documentary Lab for being an amazing sounding board.

Thanks to all our friends and family who listened to these episodes and gave early feedback. We appreciate you so much!

Thank you to the community of Edenton, North Carolina, for embracing me as family.

Thank you to the ancestors for bringing us through. We speak your names and hold you in our hearts.

Finally, we couldn’t have done this series without the support, cooperation, and friendship of Diving With a Purpose, Ambassadors of the Sea, the Society of Black Archaeologists, and the Slave Wrecks Project.

To learn more about Diving With a Purpose, follow them online at divingwithapurpose.org.

And to my mom, Lula Roberts, for being our biggest cheerleader and reminding us always that the best is yet to come.

And thank you for listening. We hope it’s been a great journey.

Want more?

Check out our Into the Depths hub to learn more about Tara’s journey following Black scuba divers, find previous Nat Geo coverage on the search for slave shipwrecks, and read the March cover story.

And download a tool kit for hosting an Into the Depths listening party to spark conversation and journey deeper into the material.

Also explore:

Dive into more of National Geographic’s coverage of the Clotilda with articles looking at scientists’ ongoing archaeological work, the story that broke the discovery of the ship, and the documentary Clotilda: Last American Slave Ship.

Meet more of the descendants of the Africans trafficked to the U.S. aboard the Clotilda, and find out what they’re doing to save Mobile’s Africatown community in the face of difficult economic and environmental challenges.

Read the story of Kossola, who later received the name Cudjo Lewis, in the book Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” by author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston.

Learn more about the life of abolitionist Harriet Jacobs, author of “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” who escaped Edenton, N.C., through the Maritime Underground Railroad.