Discovery shows Saturn's moon has everything needed for life

Enceladus is considered one of the most promising places to search for alien life. Now scientists have detected the last of six necessary ingredients: phosphorous.

The rarest element critical to life as we know it, phosphorus, has for the first time been discovered in an ocean beyond Earth, spewed out from Saturn's icy moon Enceladus.

The vital element helps make soil fertile on Earth, and researchers suggest concentrations of phosphorus may be at least 100 times greater in the hidden seas of Enceladus than in Earth’s oceans. The new findings also suggest the waters of other icy worlds may be similarly loaded with phosphorus, such as Jupiter’s fourth biggest moon Europa and Saturn’s largest moon Titan.

(Distant World Has Rings 200 Times Bigger Than the Rings of Saturn)

Phosphates, or compounds containing phosphorous, are essential to key components of life on Earth, such as DNA, RNA, and cell membranes. Of the six elements required for life—carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur—phosphorus “is by far the least common in the universe,” says Frank Postberg, a planetary scientist at the Free University of Berlin.

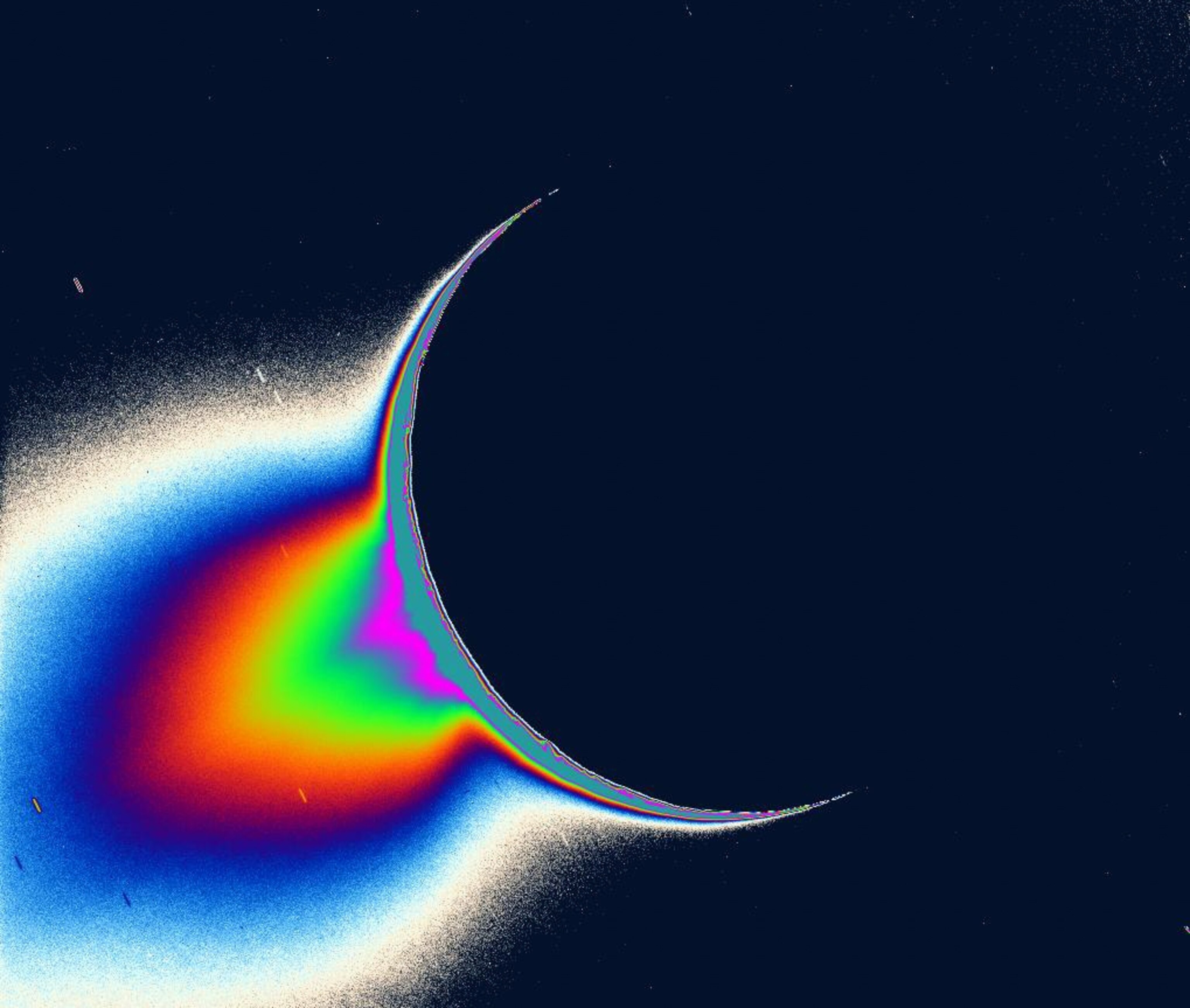

Phosphorus was the only one of these six key building blocks that astronomers had not yet detected in material from Enceladus, although the detection of sulfur is still considered tentative. Starting in 2004, the Cassini spacecraft flew into dust from the second outermost ring of Saturn, the E ring, which is composed of ice grains ejected from Enceladus. Now scientists studying the ice grains measured by Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer have detected the elusive element phosphorus, detailed in a new study in the journal Nature.

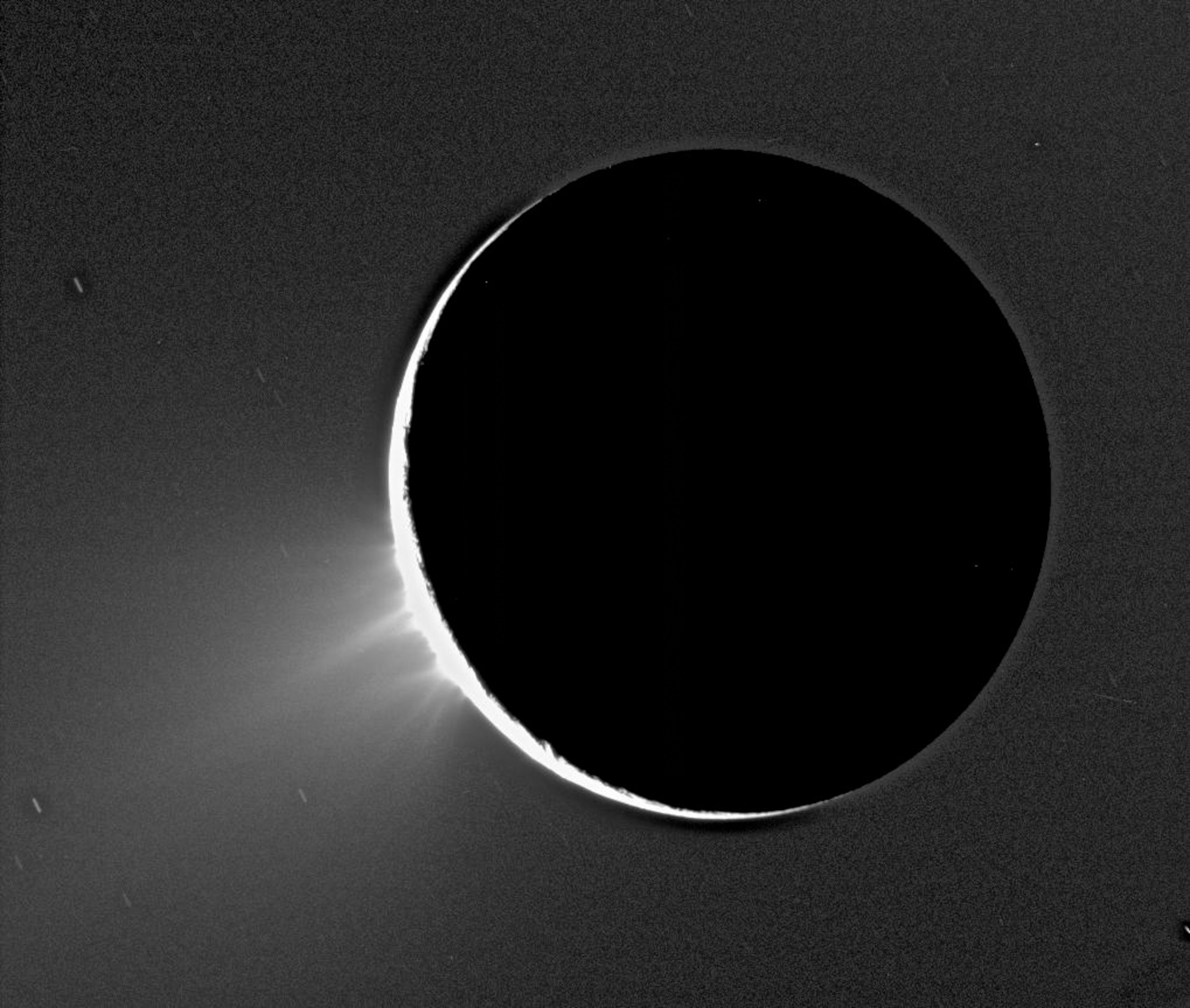

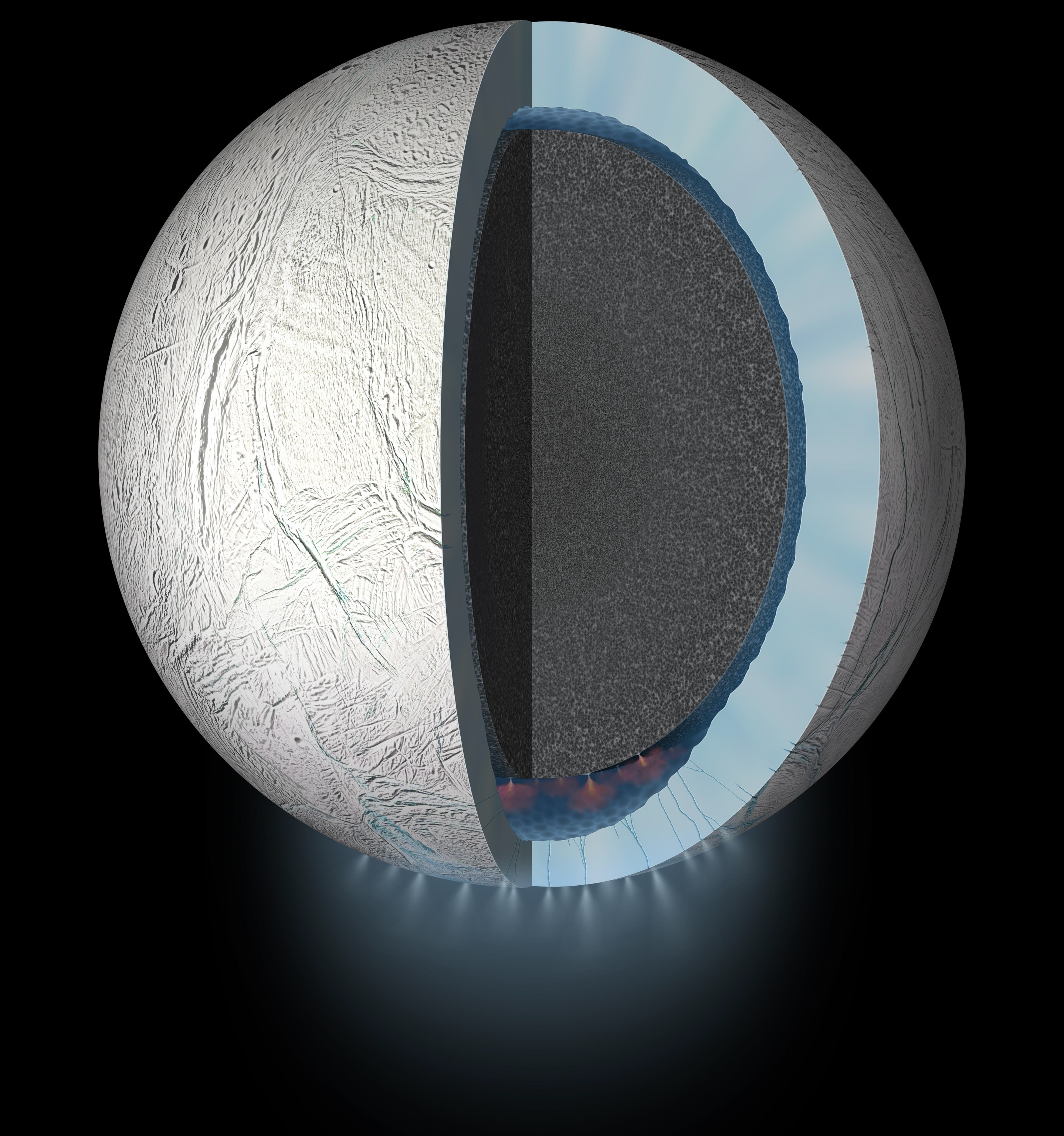

The sixth largest of Saturn’s moons, Enceladus is only about 314 miles wide, making it small enough to fit inside the borders of Arizona. When the Cassini spacecraft first arrived at Saturn in 2004, scientists expected Enceladus to be a frozen ice ball. But the next year they detected plumes of water vapor and icy particles erupting from geysers on the surface, revealing the existence of a global ocean between the moon's icy shell and its rocky core.

Postberg, the lead author of the new study, and his colleagues previously found that Enceladus’s ocean might also contain complex organic molecules.

This makes Enceladus "the most promising place, the lowest-hanging fruit, in our solar system to search for extraterrestrial life," says Carolyn Porco, a planetary scientist and Cassini's imaging team leader, who did not take part in the new study.

Searching for hidden phosphorous

Until now, no one had detected phosphorus from the ice of Enceladus or similar worlds, calling into question whether these places could truly be habitable. "People were really having doubts as to whether or not phosphorus might be the bottleneck for the possibility of the emergence of life," Postberg says.

Previous models of Enceladus and other icy ocean worlds were divided on whether these hidden seas possessed significant amounts of phosphates dissolved within them. "Phosphates don't like to dissolve in water, so it's in principle harder to find in oceans," Postberg explains.

Early research suggested phosphates may be trapped within the rocky cores of these worlds. However, more recent work hinted that phosphates could also be abundant in the oceans.

Of 345 ice grains from Saturn's E-ring that Cassini examined between 2004 to 2008, the scientists detected nine grains with phosphates.

"The most surprising thing was how clear and unmistakable the phosphate signatures are in the data," Postberg says. “It took years analyzing a lot of data, but from my perspective, this is really a bulletproof detection.”

“It is surprising that Postberg and others were able to sort through the grains and pull out the phosphorus signal so well,” says Chris McKay, an astrobiologist at NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California, who did not participate in this study. “Very impressive detective work.”

Recent work controversially suggested the detection of phosphine, a compound of phosphorus and hydrogen, in the clouds of Venus. However, when it comes to Enceladus, "there is no controversy here—phosphate and phosphine are different," says Gabriel Tobie, a planetary scientist at the French National Center for Scientific Research, who was not part of the new study.

On Enceladus, phosphates, which are compounds of phosphorus and oxygen, "do not require any exotic reactions, while phosphine in Venus is much more challenging to explain," Tobie says.

Probing the depths

Based on phosphate levels seen across the icy grains, the scientists estimated phosphorus concentrations were 100 to 1,000 times greater in Enceladus's waters than Earth's oceans. Lab experiments they conducted suggested this was possible because Enceladus's ocean is, like soda, rich in dissolved carbonates. "This soda ocean can dissolve the phosphates in Enceladus's rocks," Postberg says.

In addition, the waters of icy ocean worlds in the outer solar system—such as Pluto and Neptune's largest moon Triton—should also be replete with carbonates, suggesting they may also dissolve phosphates from rock, Postberg says. And NASA's planned Europa Clipper mission, scheduled to launch in 2024, may detect phosphates in icy grains spewed from that moon.

Though the detection of phosphates on Enceladus raises exciting possibilities, the small number of ice grains that the researchers examined leaves some unanswered questions. Future research is needed to determine whether these phosphates are truly found everywhere within Enceladus's ocean, or in just a few spots, Tobie notes.

"The next step is to go back to Enceladus and search, with suitable tools, for organic biomarkers," McKay says.