Did ancient Romans love French bulldogs as much as we do?

OK, they may not be modern Frenchies, but the remains of a beloved pet in a 2,000-year-old tomb suggest that ancient Romans may have been the first to breed brachycephalic dogs like bulldogs and pugs.

Flat-faced dogs like pugs and bulldogs, technically known as brachycephalic dogs, can be undeniably appealing: Their short noses, big eyes, and wrinkly expressions make them resemble eternal puppies, triggering the “oh, so cute!” response in humans.

Brachycephaly can be caused by several different genes, and it’s likely that people selectively bred dogs for brachycephalic features at several times and in different places—the pug, for example, is said to have originated in China more than 1,000 years ago.

Now, a remarkable discovery from a 2,000-year-old tomb in Turkey indicates that the ancient Romans also likely bred flat-faced dogs as companions. Buried alongside its likely owner, the remains of a small dog with features resembling a French bulldog are among the oldest-known examples of a brachycephalic dog ever discovered.

An ancient ‘best friend and companion’

The discovery, published earlier this year in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, was made in 2007 at the ancient necropolis of Tralleis located just outside the modern city of Aydın on Turkey’s Aegean coast. Among the Roman- and Byzantine-era tombs was one containing the remains of an adult human and the dog, dated to around 2,000 years ago. The dog was likely killed to be buried with its owner, in what may have been a tradition at the time; it was also placed carefully on its side with its head facing east, like the human it was laid to rest with.

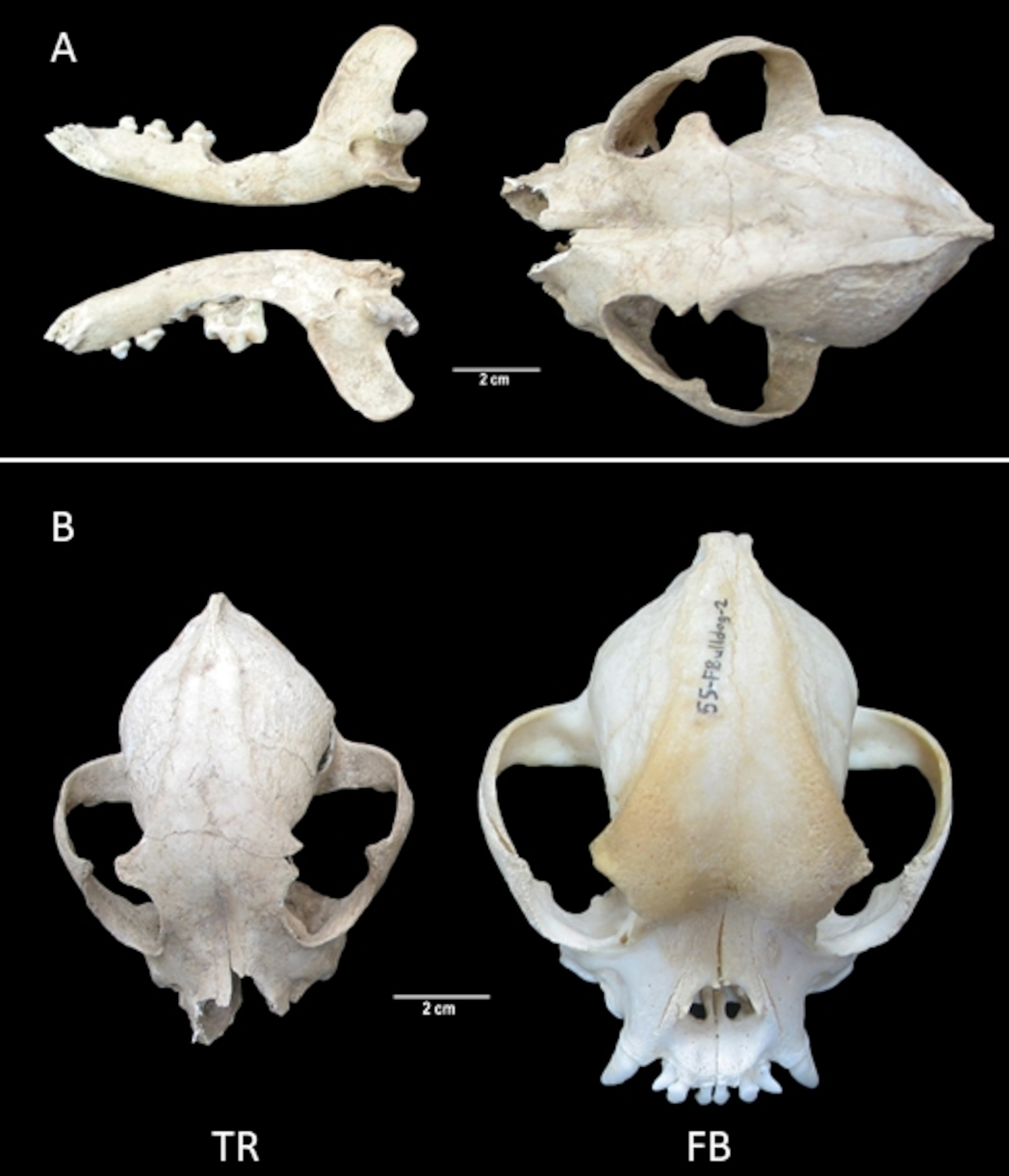

An analysis of the Tralleis dog’s remaining skull and jaw was done in 2021 by a team led by zooarchaeologist Vedat Onar of Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa. Based on skull proportions that show an acute degree of brachycephaly, the researchers determined that the ancient canine was the size of a modern Pekingese and resembled a modern French bulldog.

This is only the second find of a Roman-era dog skull that has these flat-faced features—the other was discovered in Pompeii in the 18th century, and dates from the destruction of the city by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

Although flat-faced dogs aren’t specifically mentioned in Roman writings or depicted in their art, this second find suggests that the Romans were selectively breeding such features for pet dogs, Onar says. He acknowledges the remote chance that the surviving examples may just reflect random genetic mutations limited to only those two brachycephalic dogs; nonetheless, their small size supports the idea that the dogs were bred as pets: “This dog skull found in Tralleis can be seen as a phenomenon of artificial selection, which was achieved by reinforcing desired traits,” the study notes.

Most Roman-era dogs were working animals for hunting, guarding, and herding, and injuries to their bones reveal they were often not treated well. The Tralleis dog, however, has no such injuries, while an analysis of its teeth suggest it ate little hard food. These discoveries, along with estimates of the dog’s tiny size, suggest to Onar and his colleagues that it was a cherished pet: a catella, or “lapdog” rather than a hunting dog (canis venaticus) or guard dog (canis villaticus).

“Maybe [the Tralleis dog] was the best friend and companion of the deceased, who probably included in his last will the wish of a common burial,” the study authors speculate. (Ancient Romans also gave their beloved pets individual burials; one well-known tombstone reads: “I am in tears, while carrying you to your last resting place as much as I rejoiced when bringing you home in my own hands fifteen years ago.”)

Flat faces in the genes

“It’s a surprise to me that they had these types of dogs that far back,” says clinical geneticist Jerold Bell at Tuft University’s Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine who has studied brachycephaly in dogs. “But it’s very obvious that this is what they’ve found.”

Bell, who wasn’t involved in the latest research, notes that since brachycephaly can be caused by several different genes, it’s not possible to draw a direct line between the flat-faced dogs of ancient Rome and modern brachycephalic dog breeds.

Geneticist Kari Ekenstedt of Purdue University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, who also wasn’t involved in the study, hopes that ancient DNA can be one day be extracted from the teeth of the Tralleis dog. The genetic information could not only resolve the issue of the dog’s sex (the researchers think it was male, but can’t be sure), but may also show one of the three or four genetic mutations that are now known to cause brachycephaly, she says.

Ekenstedt also notes that while it’s not likely the Tralleis dog was an ancestor of modern brachycephalic breeds, it remains a possibility—for example, genetic mutations like dwarfism in dogs, seen in breeds like corgis and dachshunds, predate the Victorian era when such breeds were standardized. “The mutations themselves might be quite ancient,” she adds.

Extreme breeding and health problems

Most modern dog breeds—including brachycephalic breeds like French bulldogs and Boston terriers—were created in the Victorian era when it was a profitable business, explains animal epidemiologist Dan O’Neill, an expert in dog brachycephaly at the Royal Veterinary College in the United Kingdom, who also wasn’t involved in the latest study.

More than a century and a half of subsequent breeding have led to the situation where some breeders see the most extreme degrees of brachycephaly as the most “cute,” leading to a sharp rise in the related health problems in flat-faced dogs.

The best known is Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome, a common breathing difficulty among “brachy” dogs. They also commonly suffer from eye problems because their large eyes may not get sufficiently wet from their eyelids; spinal problems associated with the genetics of brachycephaly; and skin problems caused by deep wrinkles around their faces, O’Neill says.

The hope among animal experts now is that the worst excesses of breeding for flat-facedness can be overcome by focusing instead on the health of the dogs.

“The idea is that we that will start to make it socially unacceptable to have the extreme versions,” O’Neill says. “That will shift purchasing desires towards innately healthy dogs.”