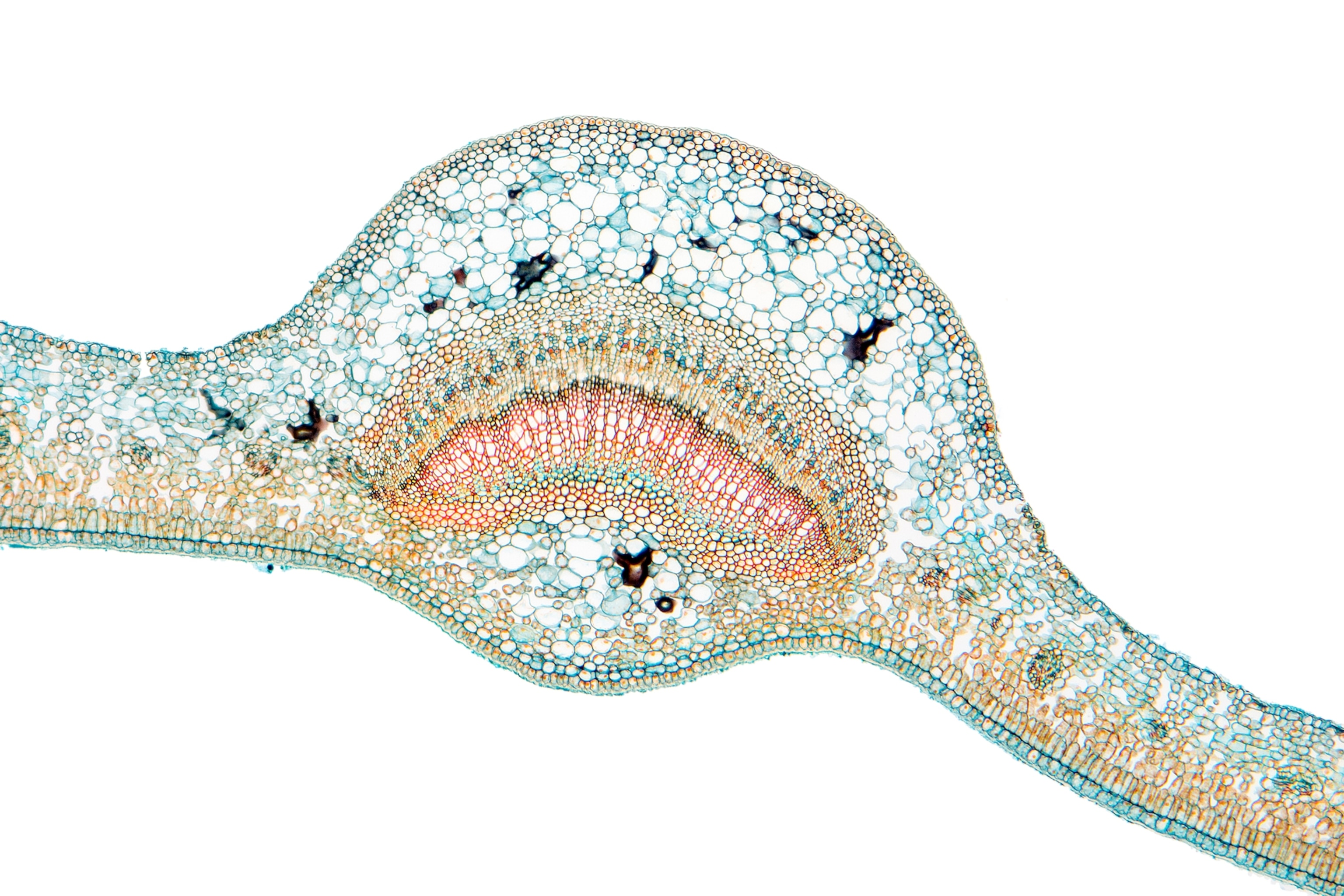

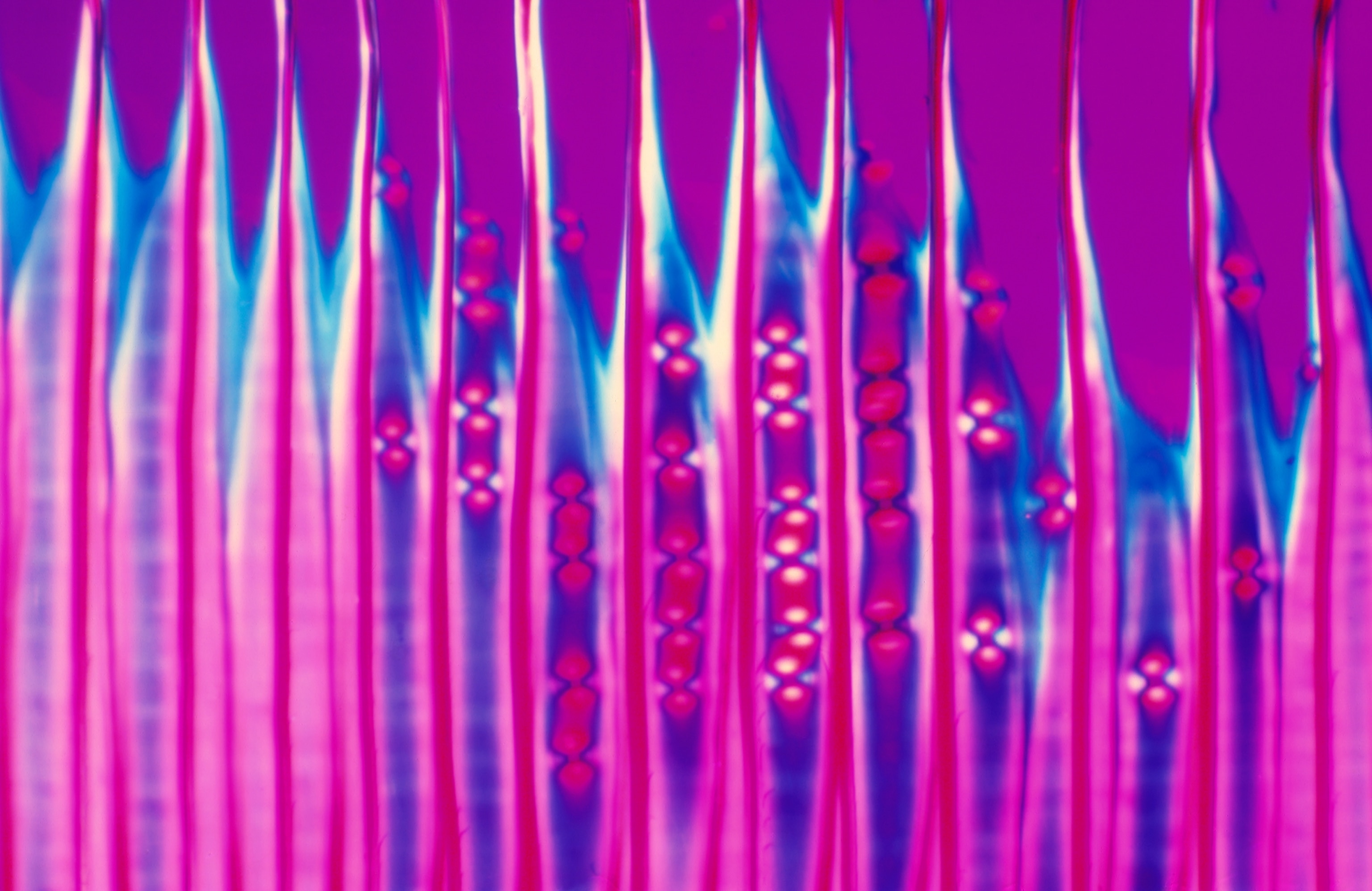

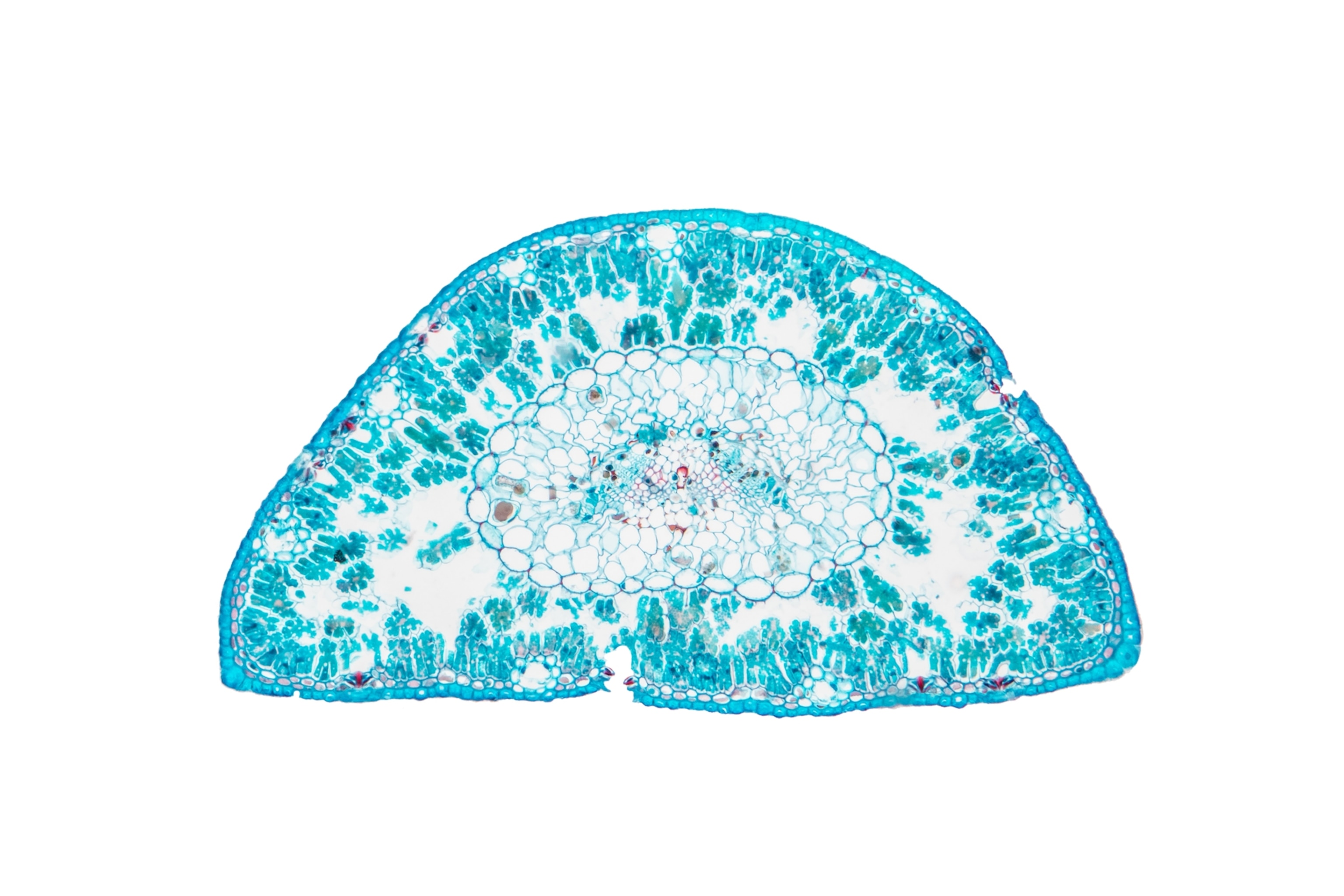

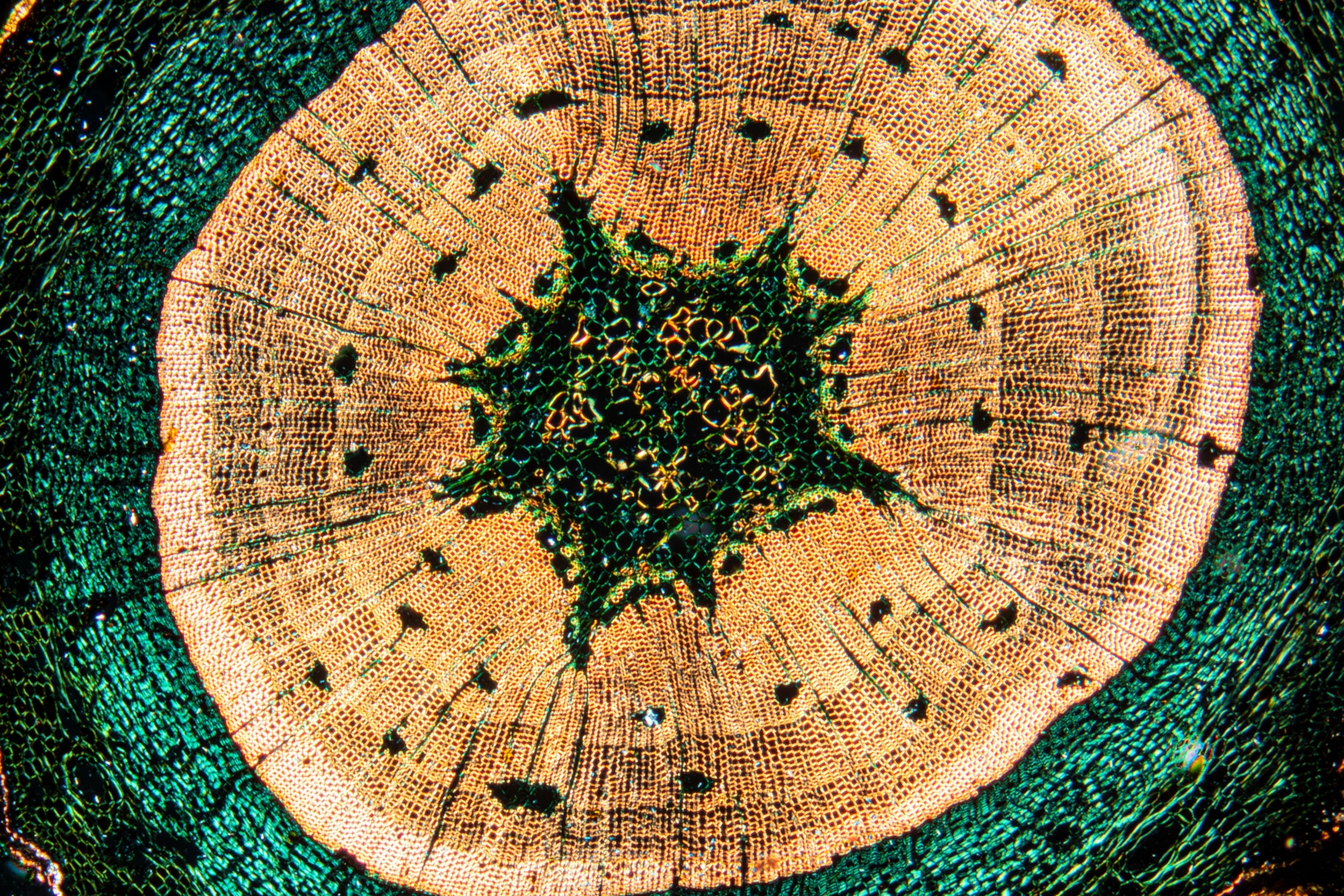

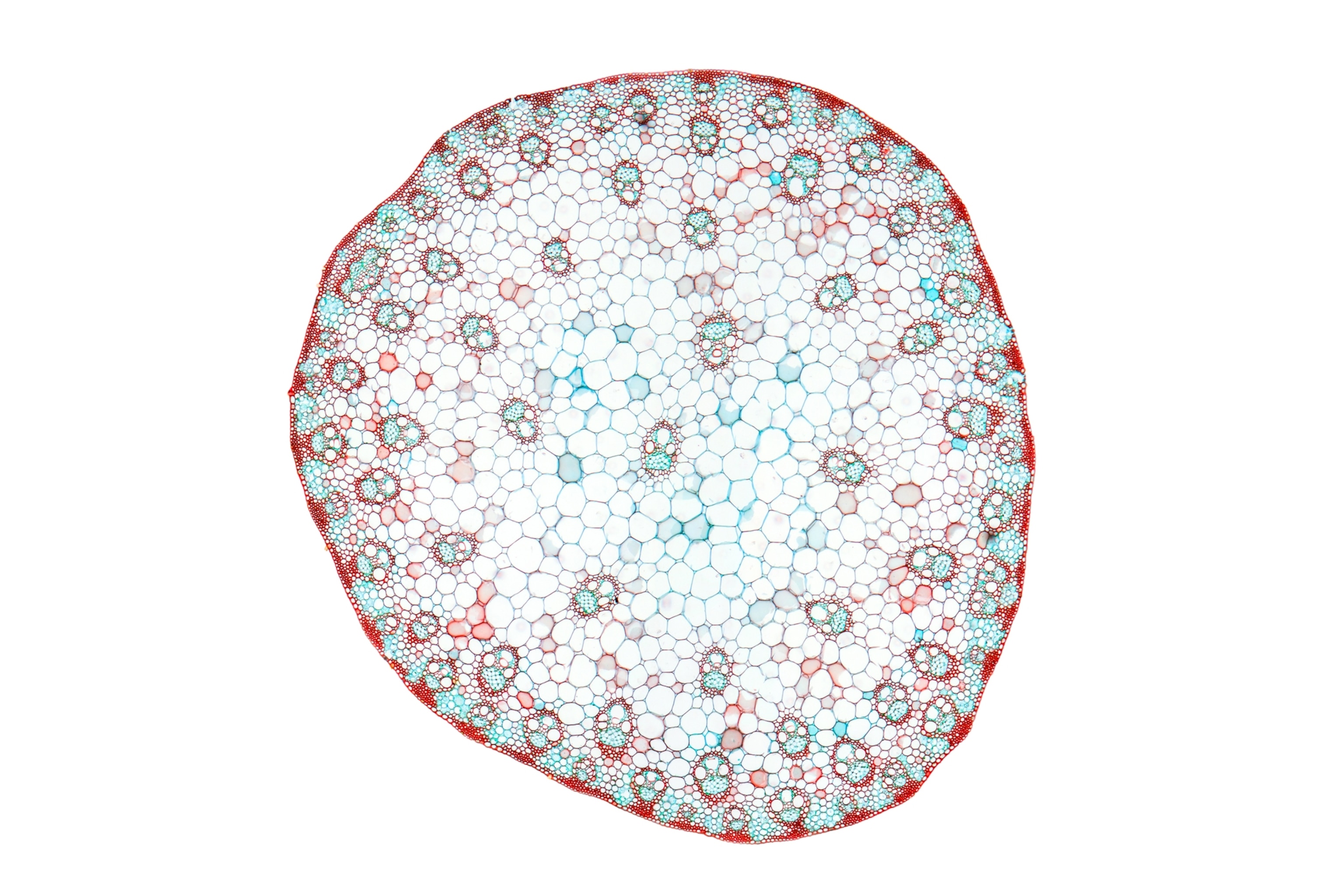

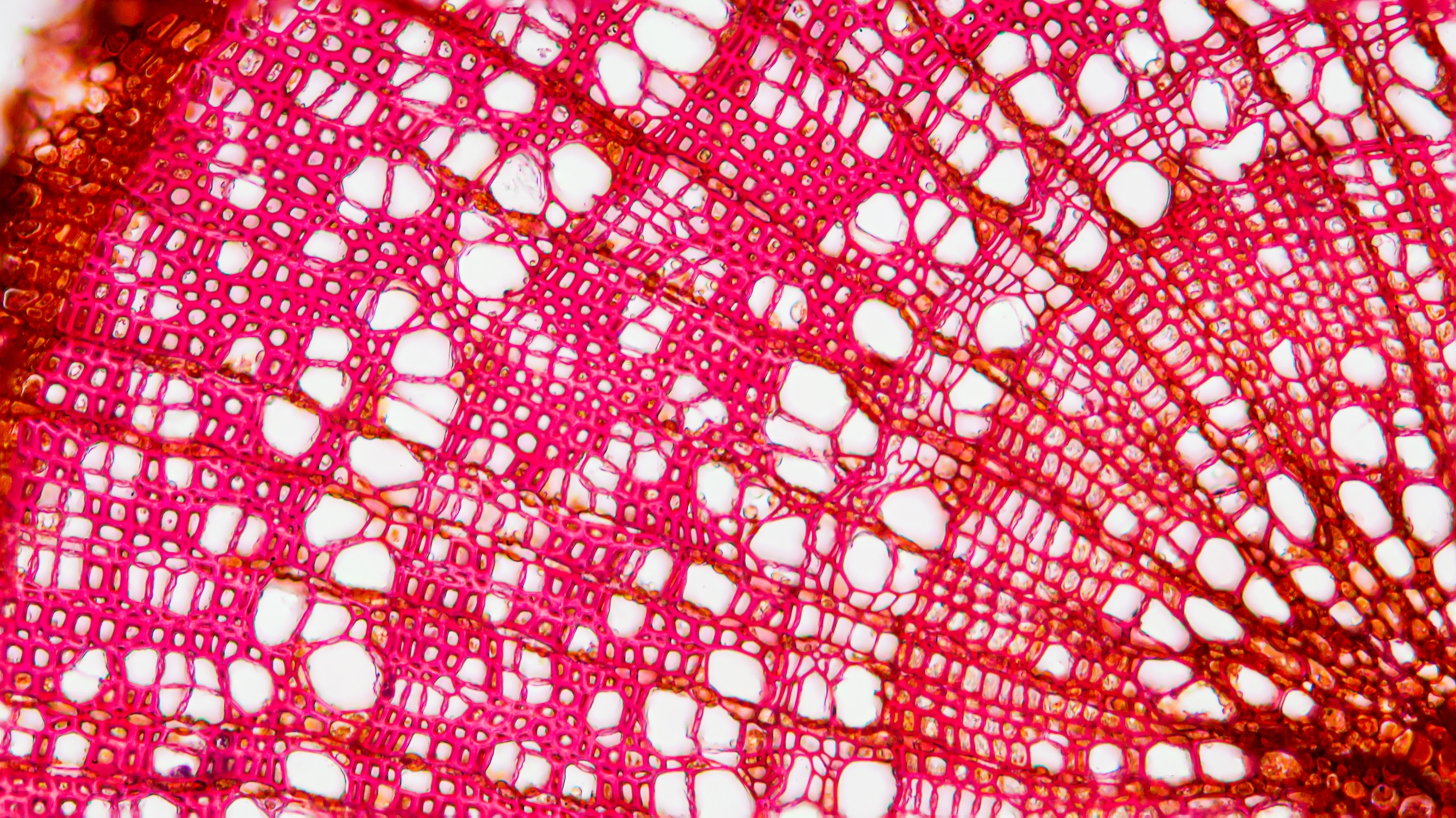

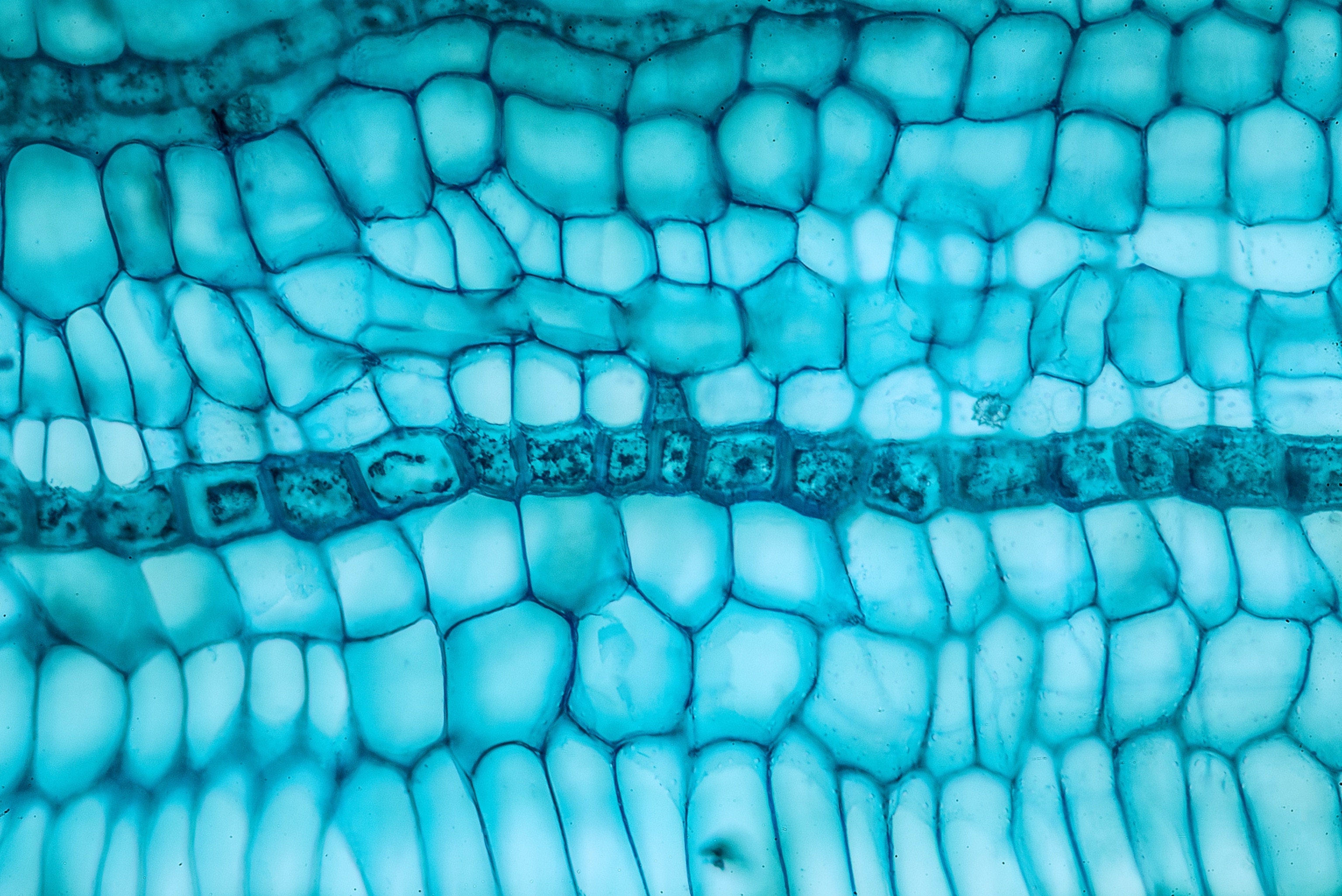

This is what plants look like—from the inside out

With his camera-mounted microscope, a photographer zooms in to the cellular level to capture the hidden beauty of poplars, pine cones, and dandelions.

Growing up on the shores of Lake Huron in the Canadian province of Ontario, Robert Berdan was never far from water. When he was in sixth grade, he received a toy microscope for Christmas. Some of the first things he saw through its lens were tiny creatures inside droplets he’d gathered from a local pond. He was fascinated with the microorganisms.

(See the microscopic universe that lives in a single drop of water.)

After eighth grade, Berdan upgraded to a more sophisticated model and realized it was a portal to another world. “The new microscope changed my life,” he says. “I could see so much more.” He began studying photography and buying cameras to fit on his microscope. He captured images of ferns, mushrooms, and trees, and learned how to develop film. He also developed his microscopy skills, so much so that he earned a doctoral degree in cellular biology and spent five years running a lab at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

But Berdan never forgot his two early passions—being immersed in nature and photographing its tiny details—and he decided to return to them. His subjects range from snowflakes to spruce trees. To see the latter under a microscope, Berdan collects a small branch and wields specialized tools to shave off paper-thin slices, which he dyes red or blue. For the final images, he often uses a process called focus stacking, in which similar photos with different focal planes are blended to achieve a more profound depth of field, and he sometimes stitches photos together to create panoramas.

“I investigate anything that might have possibilities,” he says. And he encourages others to do the same with a microscope. “Any tool that amplifies our ability to see will enhance our creativity,” he notes. “Our observations can potentially lead to new discoveries and solutions.”