Radioactive dogs? What we can learn from Chernobyl's strays

They’ve lived and bred inside the Exclusion Zone for generations—and scientists believe their DNA may transform our knowledge about the effects of radiation.

When Timothy Mousseau arrived at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 2017, one of the world’s most radioactive places, the population of stray dogs in the area had grown to about 750.

The dogs were assumed to be descendants of those abandoned after the devastating April 26, 1986, explosions and fire at the plant, the worst accident in the history of nuclear energy. Within 36 hours, Soviet authorities evacuated 350,000 residents of Pripyat, just two miles away, some with only the clothes on their backs. People were forced to leave their beloved pets behind and many never returned to the 1,000-square-mile Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

Mousseau, an evolutionary biologist at the University of South Carolina, was partnering with a team from the U.S. nonprofit Clean Futures Fund (CFF) that traveled to Ukraine to establish a spay/neuter and vaccination program to control the population. Mousseau tag-teamed with a research component: collecting blood and tissue samples for DNA analysis. He’d been conducting wildlife studies in Chernobyl since 2000. But this project offered a living laboratory to hunt for radiation-induced genetic mutations in a large number of animals. He’s now joined four missions from 2017 to 2022, with plans to return this year.

Elaine Ostrander, who runs the Dog Genome Project at the National Human Genome Research Institute, came onboard to sequence the DNA samples. Their recent publication in Science Advances characterizes the genetic structure of 302 free-roaming mixed-breed dogs and deciphered their pedigrees, identifying 15 different families, some large, some small.

These results provide preliminary, baseline data for a multi-year project that will explore how chronic radiation exposure has impacted the dogs’ genetics. Mousseau and Ostrander realized that the first step was understanding the population: who was who and where the dogs lived, as radiation levels vary widely. So Mousseau included the location of where each dog was captured when he collected blood samples.

These Chernobyl dogs are valuable to science because they’ve lived and evolved in isolation for 15 generations since the disaster. They die young, by three or four years old; 10 to 12 is normal for 75-pound dogs. Since they don’t spend much time in the gene pool, Ostrander hypothesizes that “whatever happened in the genome that allowed these dogs to survive in this very hostile environment are probably [mutations to] pretty big, important genes that do pretty important things.”

By identifying families, they can look for differences between offspring and parents. Mutations—or the potential for mutations—could be passed down from ancestors who survived the blast back in 1986.

The research has the potential to transform knowledge about the effects of radiation on mammals, including humans, the researchers say.

“Ultimately, we want to know what happened to the genomic DNA that allowed [the dogs] to live and breed and survive in a radioactive environment,” Ostrander says.

Dogs abandoned in a radiated landscape

The Chernobyl disaster spewed 400 times more radioactive material into the atmosphere than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Winds distributed it in a patchwork of high and low radioactivity.

Now, 37 years after the accident, most of the radiation comes from long-lived cesium and strontium, but other radionuclides, such as plutonium and uranium, also are in the soil. Radioactive particles emit energy powerful enough to rip electrons from molecules inside cells. This can sever chemical bonds in DNA, which can cause mutations. Cells have mechanisms to repair damage, but mutations can spark cancer, reduce life spans, and impair fertility.

The Nobel Prize-winning book Chernobyl Prayer reconstructed the terrifying early days of the disaster through oral history, including the trauma people experience when they had to abandon their pets. "Heartbroken families pinned notes to their doors: Don’t kill our Zhulka. She’s a good dog." One person remembered “dogs howling, trying to get on the buses. Mongrels, Alsatians. The soldiers were pushing them out again, kicking them. They ran after the buses for ages.”

Soon after, military squads arrived. They shot the dogs to limit the spread of radioactive contamination and disease. Some eluded their executioners, surviving in the woods around the plant and near Pripyat.

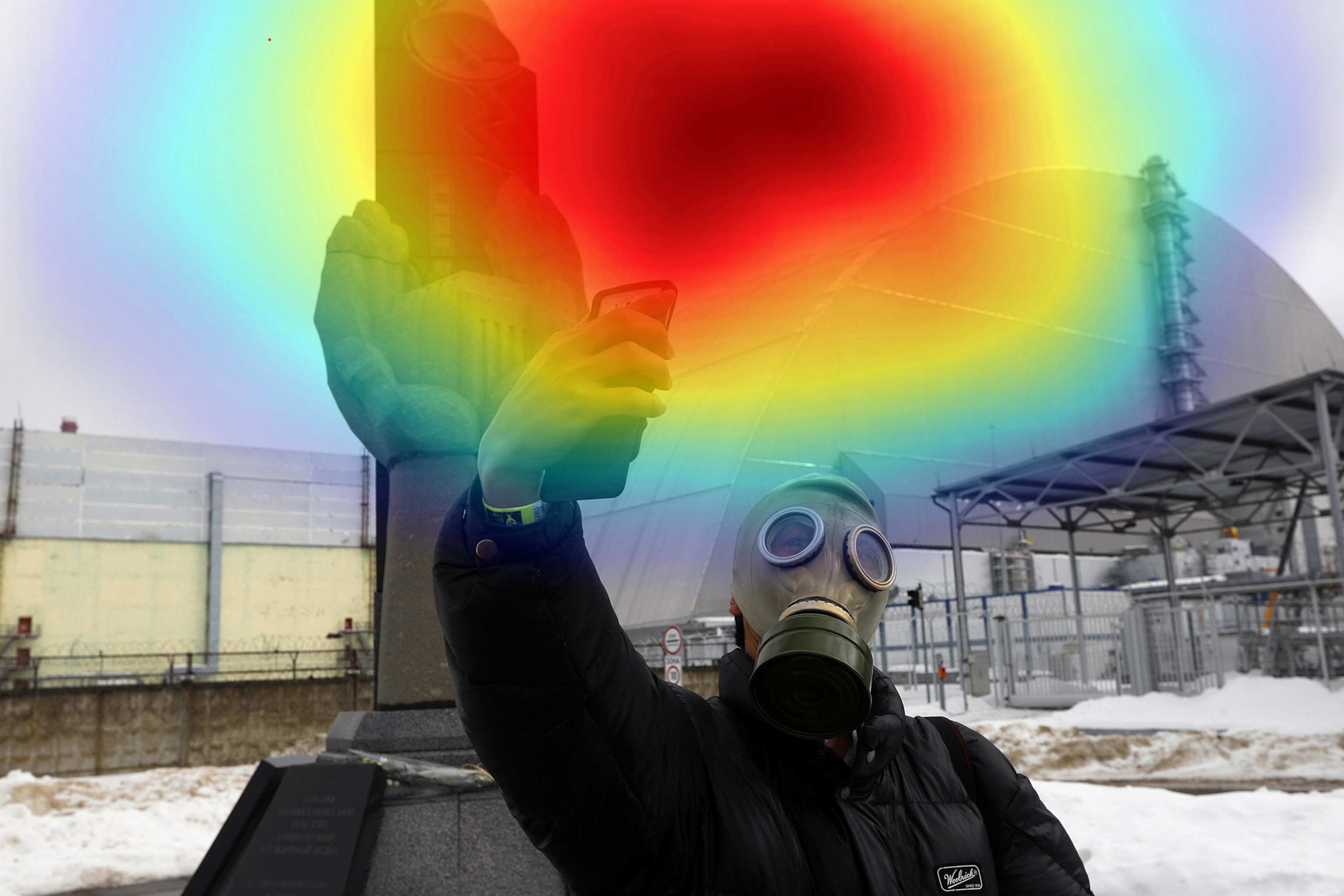

Fast forward: In 2010, construction began on a New Safe Confinement Structure over the damaged reactor. Thousands of workers poured in. Around the same time, Chernobyl became a “disaster tourism” destination. The dogs migrated to those areas and people fed them. As their numbers grew rapidly, concern about rabies escalated.

The Clean Futures Fund, founded in 2016 to provide support and health care to communities affected by disasters, realized that the dogs, too, needed help. Once the Exclusion Zone Management Authority granted permission to provide the dogs with veterinary care and population control, the CFF veterinary team set up a makeshift hospital in one of the old buildings. Mousseau set up a lab and joined the vets during procedures.

On the ground in Chernobyl

Jennifer Betz, the veterinarian who now heads the program, outlined their process. “We capture the dogs, spay/neuter them, vaccinate, microchip, tag them ... and Tim has been putting dosimeters in their ear tags. Then we release them where they came from so they can live out their lives as happy and healthy as they possibly can.” The team also provides needed medical care.

These dogs cannot be removed from the zone, she says, “because they can carry significant amounts of radioactive contaminants, either in their fur or in their bones.”

There was one exception. In 2018, 36 puppies whose mothers had died received special permission from the Exclusion Zone Management Authority to be removed to save them: They wouldn’t have survived. They were decontaminated and adopted by families in the U.S. and Canada. They’d been exposed to radiation in utero and for three-to-four weeks before they were rescued. The team will track these dogs for the rest of their lives, watching for tumors, lymphoma, or other health issues.

Researchers sometimes recover dosimeters worn for months or years, which reveal total exposure. Dogs living around the reactor endure radiation that is thousands—or tens of thousand times—higher than normal levels, says Erik Kambarian, co-founder and chairman of the Clean Futures Fund.

Identifying the canine survivors to map genetic mutations

Ostrander’s analysis identified two distinct dog populations, with surprisingly individual genetics and little gene flow between them. About half live in the vicinity of the highly radioactive power plant, including three families living within a spent nuclear fuel storage facility. The other group roams the less contaminated Chernobyl City, nine miles away, where workers live; that human population is far smaller since completion of the new containment structure. A handful of samples came from dogs up to 28 miles away in Slavutych.

Ostrander not only sequenced the dog’s genomes, but she identified their breeds, which allows her to compare these dogs’ genetics with those of similar ones that live in other, non-irradiated areas. Both populations carried DNA from German shepherds and other Eastern European shepherd breeds. The Chernobyl City dogs seem to have bred with workers’ dogs, carrying boxer and Rottweiler genes.

It’s the first such study done on Chernobyl’s large mammals, notes Andrea Bonisoli-Alquati, a biologist at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, who works in Chernobyl but was not involved in this study. He adds that it’s providing important genetic tools and methods to study large populations—and fundamental knowledge on how genetic mutations relate to disease, particularly in vertebrates.

The next steps are to look at what parts of the genome have changed over the past 37 years, Mousseau says. The team hopes to answer many questions. What must happen for pups to be born alive and to be able to grow up? Do genes that have changed coincide with what we know about radiation effects? he asks. Are there changes to genes involved in DNA repair, metabolism, aging—or novel responses that have allowed the dogs to survive? At what levels does significant harm kick in?

The hope is that these dogs—and this research—will help us better understand the risks associated with radiation exposure.