How the ‘Magna Carta of AIDS activism’ sparked a revolution

In 1983, AIDS hysteria was sweeping the country. This is the story of how a Denver conference empowered a generation—and helped shape a new era of advocacy.

Forty years ago, as the AIDS crisis began to accelerate, a group of activists aimed to remove the stigma of the illness and asserted healthcare as a human right. Their manifesto, known as The Denver Principles, sought to remove labels such as “victims” and instead adopt a new term—“people with AIDS.”

The manifesto, once described by an activist as the “Magna Carta of AIDS activism” will be commemorated at events this month, but health advocates say that even with progress there is still much to be done to recognize The Denver Principles and improve healthcare for those most impacted by HIV and other infection-associated illnesses.

How it came to be

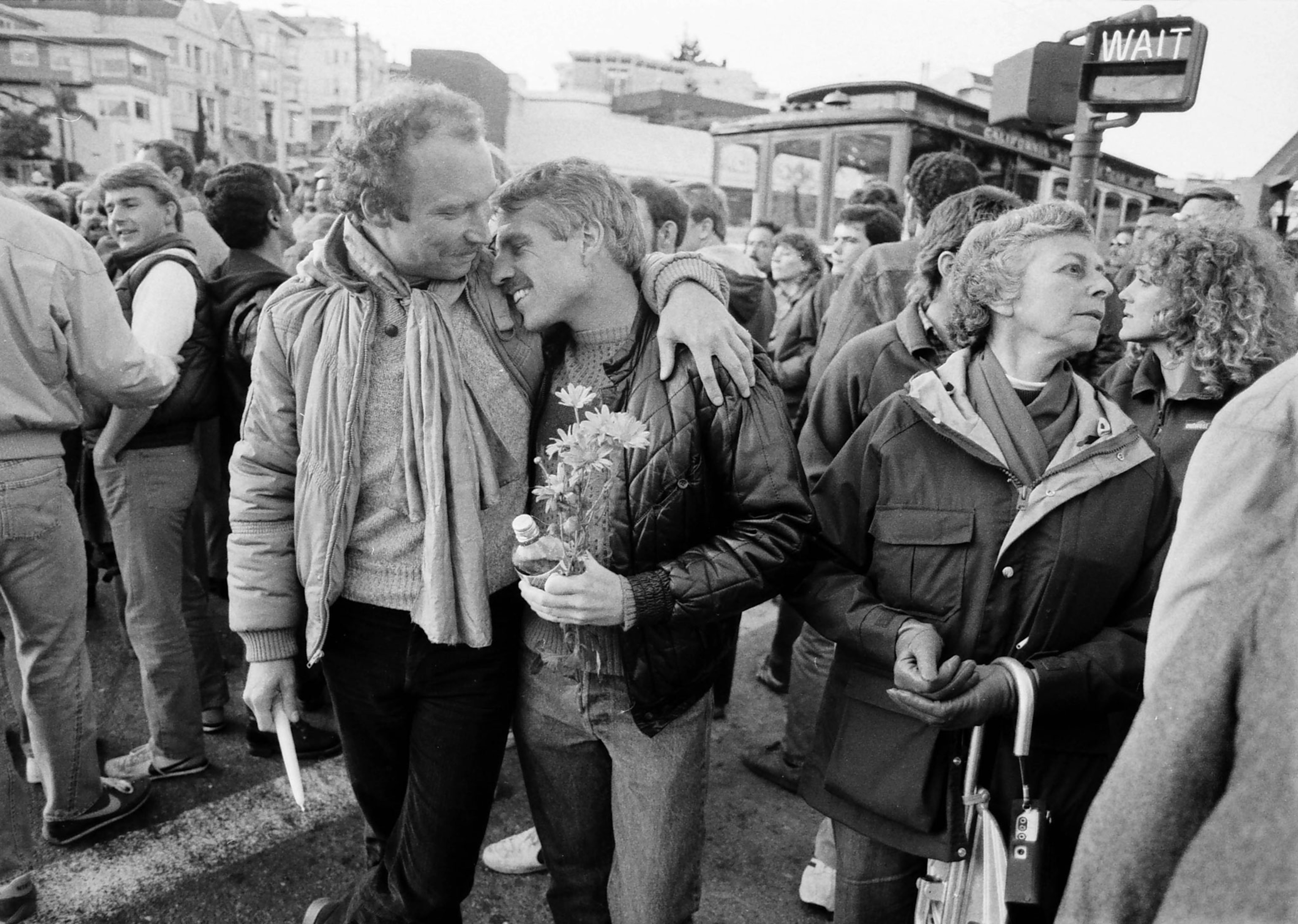

The story behind the principles started on a cool, windy evening in spring 1983, when thousands marched down San Francisco’s Market Street behind a large “Fighting for Our Lives” banner during the first AIDS Candlelight Vigil. Darkness fell on the city as the flames began to flicker like lighthouses on the Pacific Coast. Activist Mark Feldman described his frustrations of being labeled a “victim” and “patient” during the early AIDS epidemic. “I am defining myself,” he said before he placed a gold metal crown on his head. “I am a person with AIDS, a human being."

Though Feldman’s “person with AIDS” term— which has evolved to “person living with HIV”— was central to the document, he did not get to present it. He died of AIDS-related complications days before the manifesto was made public on June 12, 1983 at the National Lesbian and Gay Health Conference and National AIDS Forum in Denver. But Feldman’s ideas were conveyed by fellow San Francisco activist Bobbi Campbell and Feldman’s lover, journalist Michael Helquist.

“There was an effort to be sure that people with AIDS were represented in Denver,” says Helquist, adding that at the time it was common for people with AIDS to experience a “social death” as they were banished from their families and doctors’ offices.

The conference

“It was not a popular idea for some people to have an advisory committee of people with AIDS at the conference,” says Helen Schietinger, the co-chair of the forum. But she knew it was essential to the conference’s mission and says she helped form the committee in the months leading to the gathering.

The conference was controversial from the start. Fueled by “AIDS hysteria,” Schietinger says the host hotel had refused to include mention of the term AIDS on the conference’s signs. Attendees boycotted the establishment’s restaurants in retaliation. Tensions heightened when the 11 members of the people with AIDS (PWA) advisory committee—three from San Francisco and eight from New York City—finally met. Initially, they clashed on ideas and activism strategies. But over the course of the conference, the group and three other PWA representatives from around the country began to collaborate.

Schietinger says committee members refused to be “tokens” in the conference’s group discussions, meeting separately to draft the principles. As a nurse who coordinated a Kaposi sarcoma clinic during the beginning of the epidemic in San Francisco, she remembers caring for some of the advisory committee members who were debilitatingly sick over the weekend. “Most of my memories are in hotel rooms gathered around a person in bed and not in the conference hall itself,” she says.

Richard Berkowitz, the last living author of The Denver Principles, says the people with AIDS soon forged the kind of bond that really only happens when people are in a life and death situation.

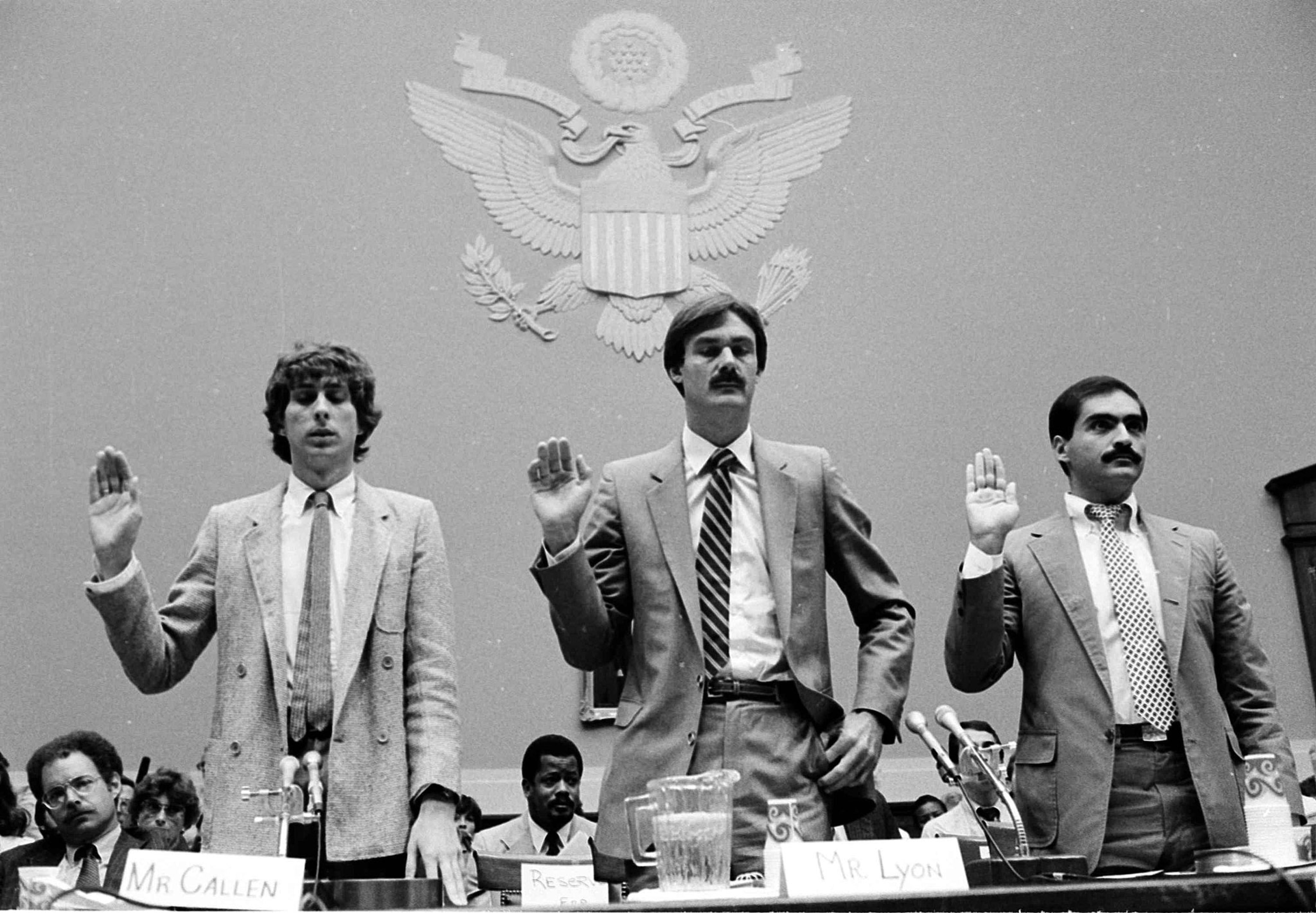

The principles were largely edited by Bobbi Campbell and Michael Callen, the latter whom Berkowitz had recently co-authored one of the first guidelines for safer sex. Inspired by the civil rights, disability, and feminist health movements of the 60s and 70s, the activists would meet in the hotel’s lobby to discuss drafts of the principles until they all signed off on the final draft.

At the close of the conference, the people with AIDS took the stage, unfurled the “Fighting For Our Lives” banner Feldman had marched behind only weeks before in San Francisco, and read the principles out loud. “It was shocking,” Schietinger says, “but it was fabulous.” As soon as they read the last right of people with HIV/AIDS “To die—and to LIVE—in dignity,” the room of hundreds erupted in a standing ovation.

“We realized at that moment that the dawn of a new movement to activism, by and for people with AIDS, was born,” Berkowitz says.

The legacy

David Duffield, historian and coordinator of the Colorado LGBTQ History Project, says the principles set the tone for the long-term impact of HIV activism for the next 15 years.

“I would almost say that the revolutionary nature and the endurance of the principles is the establishment of people with AIDS as people who are advocates for a universal human right, which is healthcare,” Duffield says.

The principles centered privacy and bodily autonomy in health care, which for generations has had roots in misogyny and racism, particularly in the medical exploitation of Black people. By upholding these ideals, the principles also spoke directly to queer and transgender healthcare rights, making the manifesto particularly relevant on its 40th anniversary as lawmakers seek to strip many of those rights.

Moreover, the principles asserted a right to sex and sexuality, and demanded freedom from stigma and discrimination, benefitting all Americans. Though most of the authors died of AIDS-related complications in the years following, their ideas would be adopted and expanded upon by numerous groups over the course of the AIDS epidemic.

But even with the advances over the years, HIV continues to disproportionately impact queer Black men, particularly in the South. And according to The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), around 38.4 million people around the world live with HIV and around 650,000 people died of AIDS-related complications in 2021.

“HIV is a racial justice issue,” says Barb Cardell, program director of the Positive Women’s Network, a national group of women living with HIV. “The people who are dying now have less access to medication, less access to health care, and less access to services.”

Cardell describes the pathbreaking 1983 Denver manifesto as lifesaving. “It is an empowerment document that talks about something so incredibly damaging and painful and turns it into a call to action.”