Lyme disease is spreading fast—but a vaccine may be on the way

Several vaccines and new treatments are in the works as the ticks that carry the disease spread to new locations. Here’s what you need to know about tick bites and your risk of infection.

It’s Lyme season in the United States and the risk of infection by the black-legged ticks that carry it is growing, especially with half of Americans now living on tick infested territory.

Without immediate antibiotic treatment, Lyme disease can cause debilitating heart and nervous system issues, arthritis, and other complications, making it difficult to cure. Although several vaccines are in development, the rising number of cases have reached epidemic levels: in the U.S., some 476,000 cases are reported each year accounting for about $1 billion in medical costs.

It’s become “a true health threat,” says Paul Mead, chief of the bacterial diseases branch at the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Clearly there is a need for new interventions and preventions.”

With several vaccines in development, researchers are optimistic they will be able to prevent the disease within just a few years. A human vaccine developed by Pfizer and its French biotech partner, Valneva, is in Phase 3 trials. Moderna is working on an mRNA version. Researchers at MassBiologics of UMass Chan Medical School are developing an anti-Lyme antibody treatment.

Diagnosing a bite

It’s easy to overlook a tick bite.

After cleaning out a shed at his home in Maryland in March 2005, radio personality at Sirius XM Radio, Earle Baily, discovered what he assumed was a spider bite. Some weeks later, he struggled with pains shooting down his extremities. Over the next months, neurological symptoms developed: he lurched to the right when walking, his joints ached, and his skin was so sensitive that touch felt like the slice of a blade. His hand movements were jerky, and one day, he couldn’t unlock his front door.

He went through six doctors and a litany of misdiagnoses.

Bailey eventually realized he must have been bitten by a blacklegged tick and had Lyme disease. Finally, an internal medicine specialist in North Bethesda, B. Robert Mozayeni, confirmed his suspicions that fall, assuring him, “I’m going to make you better.” He prescribed a cocktail of heavy antibiotics, tinctures, and vitamins. It was a two-year ordeal, but Bailey recovered and is still broadcasting, on the air.

It’s not surprising that the medical profession failed to recognize his condition when he was bitten 18 years ago, since Lyme disease was a relatively new condition and was appearing in new locations. But missed diagnoses continue to be a common problem today.

The discovery and spread of a tick-borne scourge

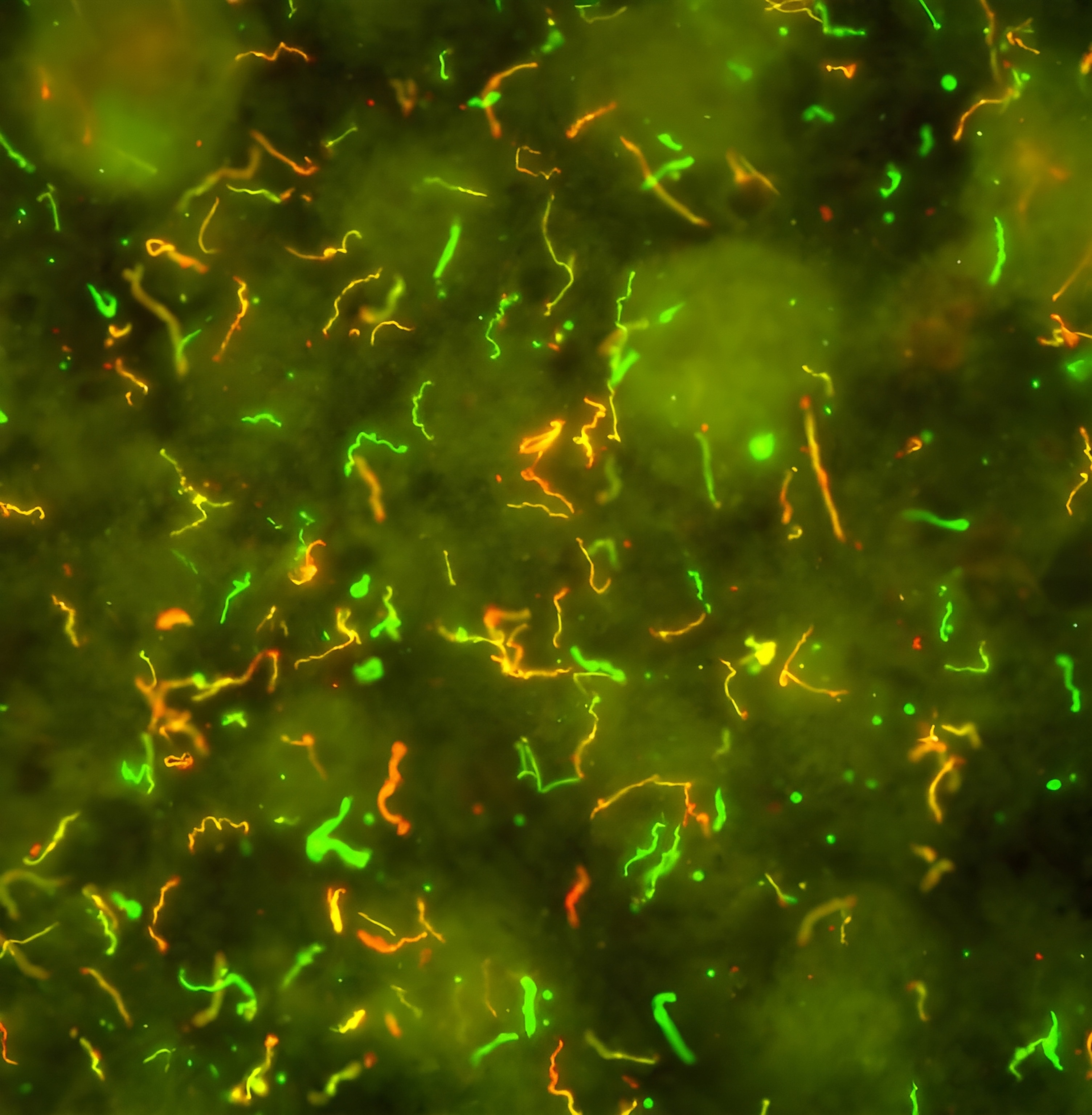

It’s been nearly half a century since the disease was first recognized in Old Lyme, Connecticut in 1975. It drew attention when a cluster of children developed unexplained, rheumatoid arthritis-like symptoms. In 1982, medical entomologist and self-described “tick surgeon” Wilhelm Burgdorfer identified the culprit: a previously undiscovered spiral bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi. The pathogen passes to humans through the bite of a black-legged (or deer) tick, but not all of them are carriers. A second, less prevalent Lyme bacterium, B. mayonii, was later found in the U.S.; two other species—B. afzelii and B. garinii—are responsible for most European infections. In western Europe, 200,000-plus cases are diagnosed each year.

Ticks pick up the bacteria while feeding on infected hosts, including white-footed mice (the primary disease reservoir), other small mammals, and white-tailed deer. B. burgdorferi then sits in a tick’s intestine for months until the arthropod latches onto a new victim for its next meal. With the influx of blood into the tick’s gut, the bacteria transform. They stop producing an outer surface protein, OspA, that anchors them to the intestine, which allows them to move to the tick’s salivary glands. The bacteria then pass through the wound and into their new host.

The process from bite to transmission typically takes 36 to 48 hours—so finding and removing a tick quickly after being bitten is critical.

What happens next isn’t always predictable. A signature bull’s eye rash may signal infection, but not always. The bacteria may initially remain localized, or rapidly disseminate throughout the body.

Preventing infection

During Bailey’s first appointment with Mozayeni, the doctor lamented that if he were a dog, he could have been vaccinated against Lyme disease: Canine vaccines have been around for decades.

There was a human vaccine, LYMErix, approved by the FDA in 1998, but it was discontinued after three years. Anti-vaccine campaigns and lawsuits claiming reactions killed sales, though inquiry by the FDA found no indication that the vaccine caused harm.

With this stigma, drug makers avoided research into new human Lyme vaccines until recently. But the challenge now is creating vaccines that will protect against the seven globally known strains of Lyme disease, says Obadiah Plante, who leads the bacteriology team at Moderna.

Both of the human vaccine candidates currently in development target the bacterium’s OspA protein, creating antibodies that prevent the organisms from suppressing OspA when the tick next feeds. This will render them immobile, imprisoned within the tick’s intestine and unable to infect a human host.

The Pfizer/Valneva candidate, VLA15, is farthest along and is being tested in a phase three clinical trial that launched in the summer of 2022. The goal is to enroll about 6,000 people aged five and older in 50 Lyme-endemic communities in the U.S., Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Sweden. The companies are testing safety and efficacy of a three-dose vaccine, followed by a booster, designed to protect against Lyme bacteria strains prevalent in both North America and Europe.

However, trials at study sites in Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard were abruptly halted in February, disqualifying about half of the study’s participants. In a statement, Pfizer cited violation of international Good Clinical Practice protocols by a third-party operator, Boston-based Care Access. They told the press that there were no safety concerns or vaccine reactions prompting their decision.

In an email, a spokesperson for Pfizer noted that the study is expected to wrap up in December 2025, but the company declined an interview until it has new results to report.

Moderna is currently applying mRNA technology—proven successful with its COVID vaccine—to bacterial vaccines, with an initial focus on Lyme disease. The company will launch human trials this summer with 800 participants in the U.S. between 18 and 70 years old. They will test two vaccines: The first, named mRNA-1982 to honor Wilhelm Burgdorfer’s work, contains a single mRNA that targets the Borrelia bacteria species that causes most cases of Lyme disease in the U.S.

The second, named mRNA-1975 to commemorate the year Lyme disease was identified, contains a mixture of seven mRNAs targeting the Borrelia species that cause most cases of Lyme disease in both the U.S. and Europe.

MassBiologics is using a different approach. Instead of stimulating the body to produce antibodies, as vaccines do, this method introduces a single monoclonal antibody targeting OspA. The benefit: “Within days after you get the subcutaneous injection, you've absorbed enough of the antibody so you're immediately immune,” says Mark Klempner, a professor of medicine and vice chancellor emeritus of MassBiologics at UMass Chan Medical School. In contrast, vaccines currently in development may take six months to confer immunity.

In lab studies, when about 20 infected ticks were placed on nonhuman primates, this antibody treatment provided 100 percent protection. Klempner says that they may produce two or three products lending protection varying from perhaps two to seven months or more. He is hopeful that they’ll be ready to apply for approval from the FDA in 2025.

Lyme season

Lyme disease risk is seasonal, and the U.S. is entering prime tick time. “Over 80 percent of infections occur between May and September,” says Klempner. But ticks may begin “questing”—seeking a blood meal—when the mercury hits 45° F. Extra vigilance is needed when last years’ larvae emerge as tiny nymphs in June and July: they’re the size of a poppyseed and may already be infected.

Meanwhile, the distribution and incidence of Lyme disease continues to expand and increase, says Sam Telford, a tick expert and professor of infectious disease and global health at Tufts University.

The Northeast, mid-Atlantic and upper Midwest are epicenters for Lyme infection, with the large majority of cases reported from Maine to Virginia and in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan. But the black legged ticks that carry the disease are moving north, south, and west.

As climate change brings warmer winters, these eight-legged parasites settle into previously uninhabitable territory. But human alteration of the landscape—suburban development—is the main driver, says Telford. Fragmented forest creates ideal habitat for the mice, other rodents and deer that harbor Lyme-causing bacteria. Today, more than 50 percent of the U.S. population shares territory with black legged ticks. Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the Northern Hemisphere.

Cases have remained stable for a decade, but the numbers are misleading: Heavily affected states like Massachusetts and New York have reduced surveillance efforts because of the tremendous resources needed to count so many infections, CDC's Mead says. The epidemic caseload underscores the need for a variety of effective tools. “We need something to help drive down this disease,” Mead adds.

There are things people can do now to protect themselves until new preventions are available: using repellents, showering after time outdoors, and cleaning up yard leaf litter. It’s also important to know the signs of tick-borne illness—an unexplained fever or a rash—and seek medical care, Mead says. “The great majority of Lyme disease cases can be treated pretty effectively with antibiotics, if you recognize it [early].”