‘Send beer!’ Life on the Roman frontier revealed by soldiers’ private letters

From party invitations to requests for warm socks, letters discovered at Vindolanda, England gave first-hand accounts of everyday life inside a Roman fort.

At the close of the first century A.D., someone wrote a letter to a soldier stationed at a Roman fort in northern Britain. The writer told the recipient that he would be sent “socks ... two pairs of sandals, and two pairs of undergarments.” The letter ended by greeting “all your messmates with whom I pray that you live in the greatest good fortune.”

This missive was discovered in 1973 during excavations at the site of the fort of Vindolanda, which today lies in the English county of Northumberland, close to the border with Scotland. Together with other items of writing found and deciphered since, the Vindolanda tablets have yielded rich information on the makeup of the Roman garrisons a few decades after the conquest of Britain began.

Written on wood, the tablets offer a trove of information on the ordinary, even mundane moments in the lives of the men—and some women—who once lived on this frontier base. The missives shed light on their military tasks, financial worries, illnesses, social invitations, literacy levels, and ethnic origins.

(A new study of the Vindolanda tablets could reveal more about life in the Roman Army.)

Rome in Britain

Launched by Emperor Claudius in A.D. 43, the Roman conquest of Britain was hampered by the revolt of Boudica in 60. Following the defeat of the rebel queen, Roman forces resumed their advance, securing Wales and swaths of northern England by 80 and penetrating what is today Scotland under the command of the general Agricola. After withdrawal of the Second Legion Adiutrix for deployment near the Danube, however, the Romans lost the chance to subjugate Scotland. They moved south and established a line of fortifications, running roughly east to west along a line.

One of the forts along this line was Vindolanda, established around A.D. 85. The original structure was soon rebuilt, and over the next 300 years, as Roman garrisons defended the northernmost point of the empire from Caledonian raiders, a total of nine forts would be built on the Vindolanda site.

The letter about socks and shoes was written very soon after the establishment of Vindolanda. A generation or so later, in 117, a new emperor was proclaimed in Rome. Dedicated to defining and securing the frontiers of his sprawling empire, Hadrian ordered the building of the defensive wall that bears his name just to the north of Vindolanda.

(Big, bad Boudica rallied the Britons against Rome.)

Peoples of Britain

Soldiers at the fort

During the period when the Vindolanda writing tablets were made and used, two army units were based at the fort: the First Tungrians, consisting of infantry, and the Ninth Batavians, a mix of infantry and cavalry. They were Roman in the sense that they belonged to the Roman army, but they were part of the auxilia: soldiers from the provinces who received citizenship after completing 25 years of service. Both Tungrians and Batavians came from the Rhineland area of present-day western Germany and the Netherlands.

Living conditions at the fort were tough. One of the tablets, a military strength report for the First Tungrian cohort, reveals that of the men at Vindolanda, 31 were unfit for duty and 10 were suffering from eye inflammation. Excavations at the site reveal the barracks were dirty, poorly lit, and infested with parasites, a good breeding ground for infections and illnesses.

(Roman legions battled barbarians along this river for 400 years.)

Preserved puzzles

Every time the Romans rebuilt the fort, substantial remains of the former structures were buried in waterlogged soil. Deprived of the oxygen necessary for rot and decay, the soldiers’ wooden tablets, leather goods, and other organic items survived in remarkably good condition (more leather shoes have been found at Vindolanda than at any other Roman-era site).

The discovery of the first tablets at Vindolanda in 1973 caused great excitement. More have been discovered since then, most recently in 2017. The documents consist of accounts and lists, military strength reports, personal letters, and literary texts.

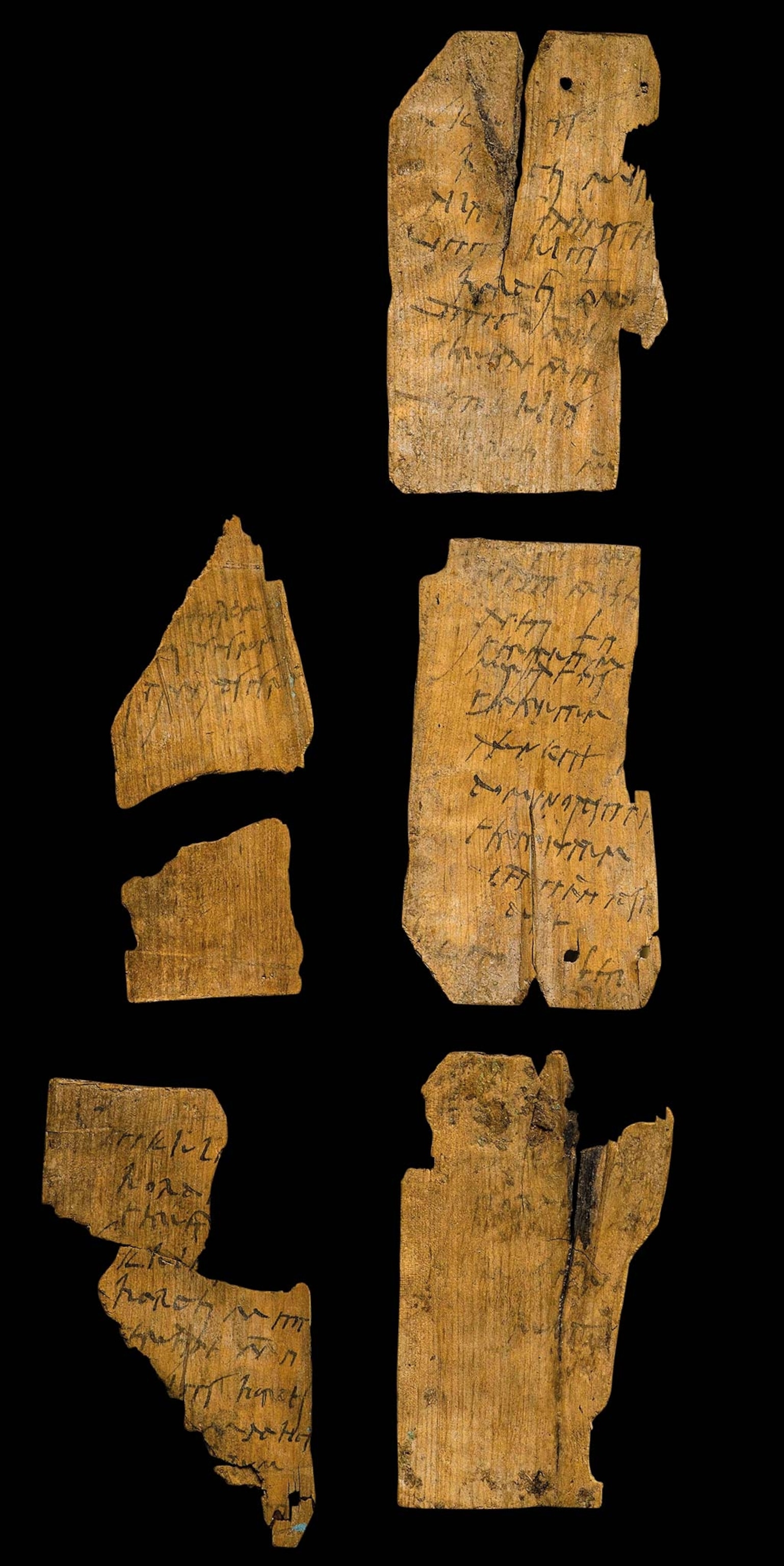

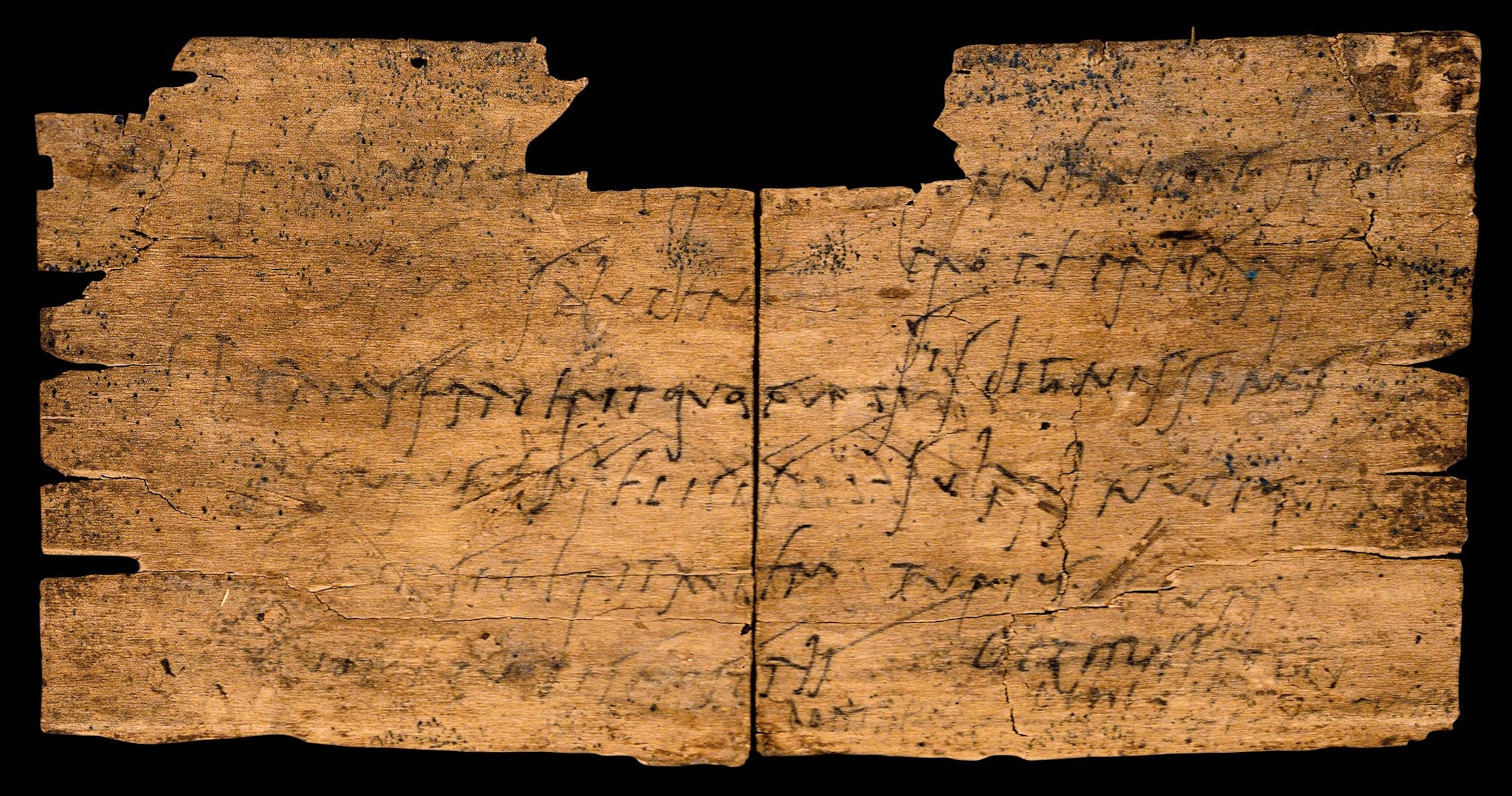

The trove held two types of tablets. One was a thin piece of wood covered in wax, which could be reused by melting the wax and smoothing it flat. While these sometimes preserve scratches made by the point of a stylus, the traces of successive messages often overlapped, creating a jumble of letters impossible to decipher.

The other type was meant for single use. Wood tablets were coated with only a thin layer of beeswax to prevent ink from spreading. Even in the case of the single-use tablets, the ink has often faded and become illegible. Sometimes scratches are visible, if only under a microscope or in an enlarged photograph. Sometimes there are just spaces, which means guessing how many letters might be missing and trying to deduce what the words might have been from the context. Deciphering the texts is a painstaking task, requiring an exhaustive knowledge of Latin—and all the slang and abbreviations employed by the Roman military.

Newspapers seized on the homely account of the dispatch of socks and shoes. Was this letter sent by a kindly mother concerned that her soldier son was uncomfortable in this bleak posting on the Roman empire’s northern border? Such an interpretation is possible, although on the whole it seems more likely that the letter detailed a commercial transaction.

The writing tablets survived because of luck—and because they were thrown away. It is most likely that they were mailed to some-one at Vindolanda, unless the text belongs to a drafted rather than a final polished letter. A few may just have been discarded accidentally, but historians believe that nearly all were dumped because they were not worth keeping any longer, especially when the owner was about to move to another posting and had to decide what was really worth carrying.

Few texts are complete, and the task of deciphering each one is akin to solving a crossword puzzle in another language and without any real clues. They are snatches of communication, only ever heard from one side, by strangers who speak to, and of, other strangers. Sometimes there are snippets of enough messages to create some sense of who someone was, their position, their family, and friends. But even then?There are many gaps. Did the shoes in that first letter ever actually arrive? No response has been found yet, so their fate is likely to remain unknown.

The pen and the sword

(How everyday items peel back the curtain on ancient Rome.)

Furloughs and favors

The tablets offer snapshots into daily routines.The following is a complete version of a common document, probably written each morning:

15 April. Report of the Ninth Cohort of Batavians. All who should be are at their duty stations, as is the baggage. The optiones and curatores made the report. Arcuittius, optio of the century of Crescens, delivered it.

Other texts note men assigned to special duties, such as making shoes or building the bathhouse. Stone structures, like Hadrian’s Wall and the forts along it, are the most visible Roman remains, but in the early phases at Vindolanda, construction was in timber, with wattle-and-daub walls. Archaeologists have found the early bathhouse—no doubt the one mentioned in the text—which was most likely the first building made in stone.

(Along Hadrian’s Wall, ancient Rome’s temples, towers, and cults come to life.)

Requests for furlough are found among the tablets (none state how long the period would last). Friends and family kept in touch by letter. In one case, money worries predominate: “Unless you send me some cash, at least 500 denarii, the result will be that I shall lose whatI have laid out as a deposit ... and I shall be embarrassed.” This plea was in a letter about the sale and purchase of grain, hides, and sinew; many other letters deal with trade.

Even though Vindolanda was on the very edge of the empire, it was fully connected with the wider markets of the Roman Empire. There is talk of bad roads delaying the transport of goods, but there is always the sense that just about anything that could be bought would be available for those who could afford it. The shoes and garments mentioned in the first letter are matched by everything from hunting nets to oysters. Quite a few tablets were written by slaves and detailed purchases made by senior officers at the bases.

High society

Among the surprises of the Vindolanda tablets were the references to the women of the garrison community. The praetorium, the commander or prefect’s house, was one of the grandest buildings in any base, designed around a central courtyard and in size and shape comparable to a reasonably grand house at Pompeii. These men were equites, the social class just below the senatorial order and men of some standing. Prefects spent some three or more years in post and brought their families and households with them.

One of the most celebrated of the Vindolanda writing tablets is that written by Claudia Severa, wife of the commander at Coria, inviting Sulpicia Lepidina, wife of the prefect at Vindolanda, to her birthday party on September 11. Most of the text was written by a scribe, but in what is surely her own hand, Severa added,“I shall expect you, sister. Farewell, sister, my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail.” Her message is probably one of the earliest surviving samples of a woman’s handwriting in Europe. Severa and Lepidina must have corresponded regularly, doing their best to maintain the same sort of connection as they would have had in Rome.

Lepidina’s husband, the prefect of Vindolanda, was called Flavius Cerialis. A woman named Valatta wrote to him, asking that he “relax his severity and through Lepidina that you grant me what I ask.” Patronage was central to Roman society, and women, as much as men, played their part in this network of recommendations and favors. Archaeology has added other vivid details to Lepidina’s life. One of her shoes has been found, an elegant and expensive one, perhaps discarded because so important a person did not need to have it repaired. Also unearthed were shoes belonging to her children.

Flavius Cerialis’s name suggests that although the prefect was a citizen and an eques, he was also a Batavian. One decurion (the commander of a cavalry troop) addresses him as “my king,” making it possible that he came from the royal family of the tribe. The relationship between this commander and his soldiers most likely differed from those in most army units. In the same letter, the decurion asks for orders, whether he was to take all or just half his men to a particular location. Perhaps more urgently, at least as far as the troops were concerned, he informed his commander that “My fellow soldiers have no beer. Please order some to be sent.”

The prefect's correspondence

"Hostilius Flavianus to Cerealis, greetings. A fortunate and happy New Year ...

Flavius Cerialis to Brocchus, greetings. If you love me, brother, I ask that you send me hunting-nets ...

[Claud]ius Karus to Cerialis, greetings ... Brigionus has requested me, my lord, to recommend him to you. I therefore ask, my lord, if you would be willing to support him in what he has requested of you. I ask that you think fit to commend him to Annius Equester, centurion in charge of the region, at Luguvalium, [by doing which] you will place me in debt to you both in his name and my own. I pray that you are enjoying the best of fortune and are in good health. Farewell, brother."

(While Rome was falling, these powers were on the rise.)

Local conflicts

Vindolanda was a frontier outpost. The later building of Hadrian’s Wall makes clear that some form of military threat was perceived by the empire. Perhaps surprisingly, given the siting of the fort and its military nature, it is not known how much, or how little, fighting occurred in the region. Among the tablets, there is scant evidence. The First Tungrian cohort had six men in its hospital listed as volnerati, which most naturally translates as “wounded,” although might just mean “injured in an accident.”

The tablets make almost no mention of local peoples. One fragment notes that “the Britons are unprotected by armor. There are very many cavalry. The cavalry do not use swords nor do the Brittunculi mount in order to throw javelins.” Brittunculi is a diminutive term—“little Britons” or “wretched little Britons”—and suggests the author held them in contempt. However, the word never appears elsewhere, making it hard to know whether his was a typical or extreme attitude for a Roman officer stationed in the province.

Excavation continues at the Vindolanda site, and new discoveries are made every season: from weapons to flatware, jewelry to armor, each artifact, much like the tablets before them, brings the everyday realties of life for Roman auxiliaries on the frontier into sharper focus.