She shined a light on the disease no one wants to see

The brain disease CTE has become tied to professional football, but Ann McKee helped discover that even in high school and college, a player’s risk doubles every few years.

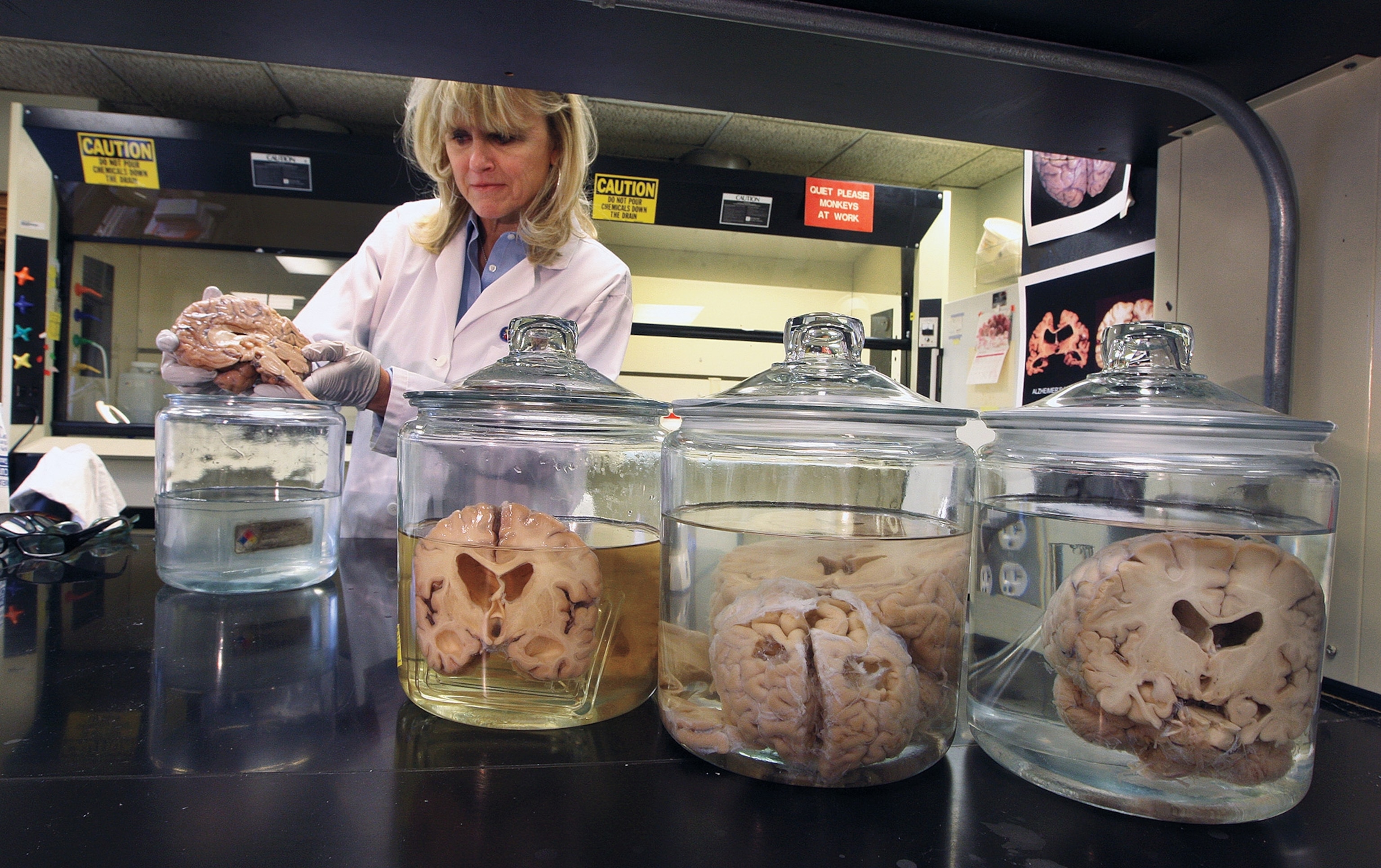

Ann McKee has lost track of how many human brains she’s held. “Probably 3,000, not anything more than that,” she says casually. Most people haven’t held even one. But one of the largest collections of brains in the world lies nestled in the Boston area, and McKee is its steward.

People donate their brains to the VA-BU-CLF (UNITE) Brain Bank, which McKee founded and directs, as part of the uphill battle to understand the neurodegenerative disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) that arises from a series of mild blows to the head. Historically, such injuries have been brushed off as of little consequence, but McKee has been tireless—often in the face of pressure from professional sports associations, whose business would be easier if she were wrong—in showing that such trauma, if repetitive, can lead to a brain disease that keeps progressing even after the hits stop.

“That whole concept is revolutionary,” she says. “I am not going to hesitate to use that word.”

Focusing on the tau

When McKee first inspects a brain for CTE, she’s looking for big signs of injury: Sometimes the corpus callosum—the structure that enables the left and right sides of the brain to communicate—is split. Often, there’s damage to the frontal lobes, which handle higher-order executive functioning, and to the hippocampus, where long-term memory is stored. Altogether, the whole brain is likely shrunken. What should weigh about 49 ounces (1,400 g) is often down to about 35 ounces (1,000 g).

On a microscopic level, she sees unusual patterns of tau, a protein that can be toxic to neurons. Later, she’ll learn about the major personality changes witnessed by the donor’s family: aggression, impulsivity, depression, memory impairment, and sometimes, ultimately, death by suicide.

By the time a brain gets to McKee, she’s seeing CTE at its worst and most progressive, and after a person has already died. But it’s the life of the person she’s learning about through pathology that stays with her. “To look at another person’s brain, to me, there’s a high level of trust and privacy,” she says. “I do feel very honored in a funny way that I have this privilege.”

She remembers the stories and maintains a clear visual memory of hundreds of the brains she’s worked with. The best known one belonged to Aaron Hernandez, convicted murderer and tight end for the New England Patriots football team. “Just an incredible brain with tons of disease,” she recalls within a millisecond.

The disease no one wants to see

CTE has become indelibly tied to professional football, an inconvenient reality that American sports culture can’t stand and can’t stop misunderstanding. The real takeaway is that no amount of protection from concussion will stop players from developing a disease that has nothing to do with concussions—an extreme outcome of play—and instead has everything to do with the basic body-colliding elements the game requires of its participants. This also makes CTE a you-and-me problem, not just one for professional athletes.

McKee says one of the most disturbing studies she has worked on was in 2019, when her lab reported that for every 2.6 years of football played at any level—high school, college, or professional—an athlete’s risk of CTE doubles. The culprit is the types of hits to the head that are so endemic to the game, and so seemingly mild, that most people play right through them.

One of the most frustrating aspects of the human body is that a vital organ carrying your whole life inside its folds is housed in the worst possible place: inside a skull bone rife with sharp protrusions just waiting to poke the brain’s delicate tissue. Every time an impact hits the body, it’s like shaking a ripe raspberry inside a walnut shell. “I don’t think we’re making a dent at all in really how many players right now are at risk for CTE,” McKee says.

And the public’s focus on sports overshadows how the same reality affects those experiencing repeated head trauma from domestic violence, uncontrolled seizures, or military service. Like climate scientists, she feels she’s “talking into the void. What will it take for people to wake up?” Probably something shocking, like a way of identifying CTE in the living, not just the deceased.

Finding biomarkers of the disease in blood or cerebrospinal fluid—the liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord—is key to that advance. McKee thinks that’s about five years away.

For the love of brains

The naysayers began to close in on McKee. McKee’s findings about CTE were simply too observational, they claimed. She wasn’t publishing enough academic papers. She leaned too heavily on pictures—where were her graphs?

“That’s scientific discovery for me, I’m a neuropathologist,” she says now, still bristling. “It’s like, ‘I know you can’t see this under the microscope, but I can, and this is what I do.’ This is what I spent my whole life doing. To me it was black and white.”

McKee got busy. She founded the brain bank, which today houses about 1,200 brains. She collected data; she made those graphs—and enlarged pictures of microscope slides to a scale where even an untrained eye could appreciate a pattern lifting from the noise. She published hundreds of papers. And in 2011 she testified before the U.S. Congress about the prevalence of CTE in athletes and military members.

“Now … we’re flooded with data, and everything that we originally hypothesized actually was confirmed,” she laughs.

Questions ahead

McKee still has many questions about how this disease works. Although tau is key to diagnosing CTE posthumously, there’s still no clear link between the protein and the most devastating aspect of the disease: the personality changes that can destroy a person’s life and sense of self and lead them to take their own life. “So what is it in the brain that makes those changes?” she wonders. “That’s actually one of the most critical questions.”

About 150 of the brains she has access to right now are from donors under the age of 34; a majority died by suicide.

There is also a paucity of women’s brains in the bank McKee runs, leaving open many questions about whether the risks of CTE have any differences across the sexes, an increasing concern as professional women’s sports gain more traction and more women sign up for military service.

There is also, of course, the perennial nature-versus-nurture question: How much of this neurodegenerative response to brain injury is genetic, and how much of it is because of specific life events? But in the end, it’s not the promise of going down any one of these pathways of scientific inquiry that keeps McKee coming back day after day, it’s just a pure love of brains.

“There’s just so many mysteries about the brain that I can be very passionate about doing brain science,” she says. “To me, it defines us.”