Giant Sunspot Now Aimed Directly at Earth

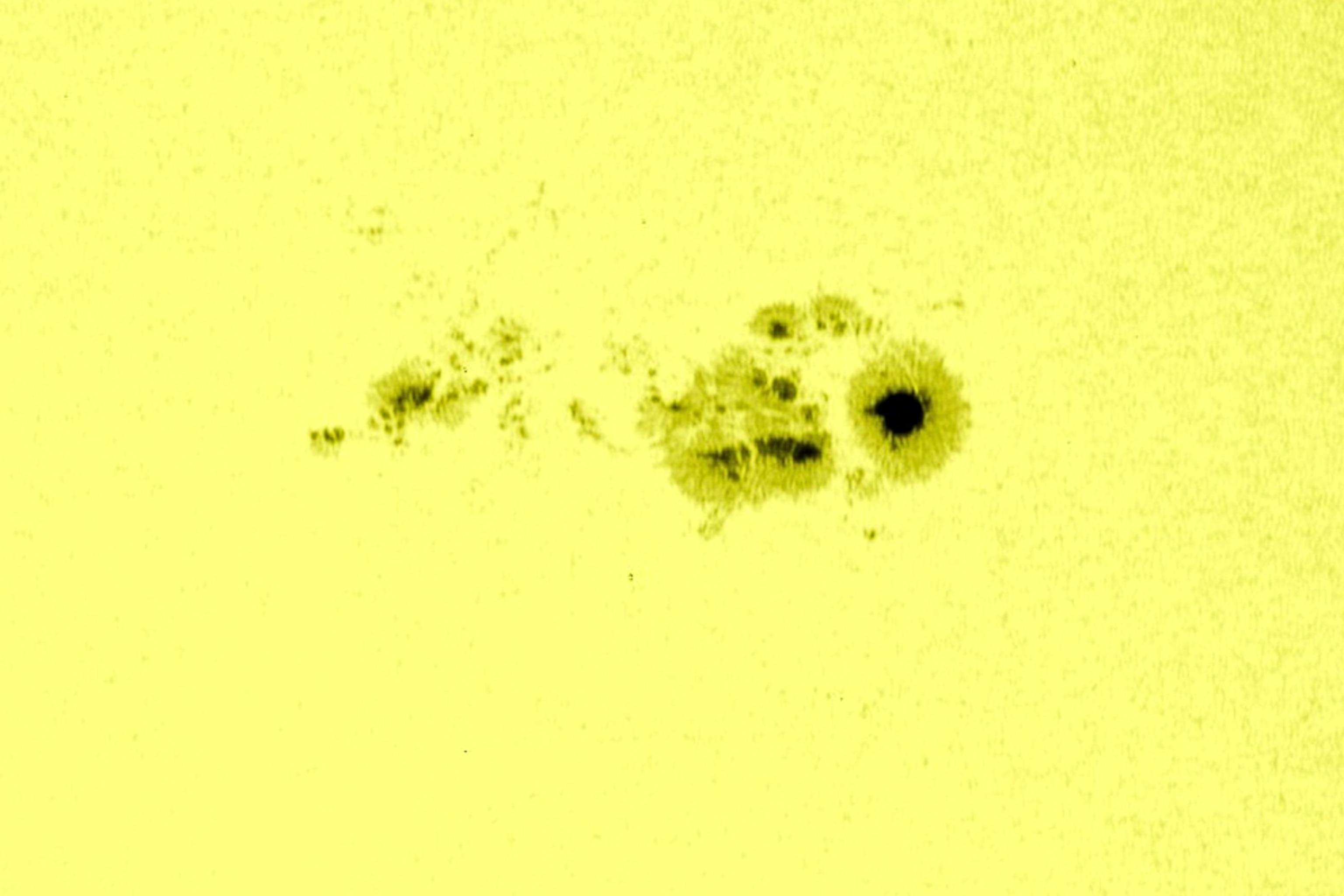

Active region wider than Jupiter could flare up at any time.

The largest active region seen on the sun since 2005 has rotated to the center of the sun's face, as seen from Earth—which means any eruptions it produces will be aimed right at us.

Dubbed Active Region 1339, the cluster of magnetic activity was first spotted by satellites as it started making its way around the sun's northwestern edge. The monster spot came into view of Earth-bound telescopes last week.

Astronomers soon realized this is not your average sunspot—it's a giant cluster of sunspots, several of which are larger than our entire planet.

In fact, viewed from Earth, AR 1339 is large enough to be visible to the naked eye.

Watch video of AR 1339 from November 1 to 8 taken by a NASA satellite.

"It's not very often that you get naked-eye sunspots," said Philip H. Scherrer, a research professor at Stanford University. Scherrer cautioned that people should never look directly at the sun—always use solar-grade filters on optical equipment, or view the sun with indirect methods, such as pinhole projection.

After releasing a few X-class solar flares—the most powerful types of flares—on November 3 that were aimed away from Earth, AR 1339 remained relatively quiet. But it's now been pointed at Earth for several days and could unleash a new round of eruptions at any time.

Huge Sunspot to Trigger Intense Aurorae?

A sunspot is a magnetically active region on the sun that appears dark because it's relatively cooler than the surrounding area—6,000ºF (3,300ºC) versus 10,000ºF (5,500º C).

Many of the sunspots that make up AR 1339 are easily as large as Earth, and the entire cluster is estimated to be approximately 17 times the width of our planet—even wider than Jupiter.

Sunspots are where solar flares are most likely to occur, since the magnetic fields in these active regions can build up enough energy to break, releasing bursts of intense radiation into the solar system.

If aimed toward Earth, this outpouring of energy can interact with our magnetosphere, infusing molecules in the atmosphere with extra energy that then gets released as light, producing aurorae.

(Related: "Biggest Solar Flare in Years—Auroras to Be Widespread Tonight?")

Exceptionally strong magnetic storms create brighter, more dynamic aurorae, such as those seen on October 24, when northern lights were reported in the U.S. as far south as Oklahoma, Georgia, and Texas.

"As AR 1339 rotates, it will move past the prime location for magnetic connections between the Earth and sun," said Dean Pesnell, project scientist for NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory.

That means that, while Earth will soon be out of range of a direct hit from any strong flares from AR 1339, "aurorae may increase in intensity and frequency, as there is always more stuff leaving the sun when a large active region is in view," he said.

"But without a large prominence eruption, we will not have a magnetic storm here at Earth that drives the brilliant aurora."

Sunspot's Risk to Satellites, People

While aurorae are beautiful to watch, the sun's electromagnetic outpourings also carry some risk. The x-ray energy from solar flares can change conditions in Earth's upper atmosphere, which can disrupt or even knock offline communications satellites.

(See "Solar Megastorm Could Cripple Satellites for a Decade.")

In addition, the extra radiation can pose health concerns for commercial pilots and astronauts, such as the crew currently aboard the International Space Station.

"If there's a major flare, they're at risk," Stanford's Scherrer said.

Should the ISS be in the line of sight during a strong flare, the crew would have literally only minutes of warning, and the best the astronauts could do would be to move to a part of the station that has more protective layering.

Will the Sun Show Some Flare?

While it's currently not possible to accurately predict solar flares, the chance of AR 1339 firing a flare toward Earth in the near future can't be ruled out.

"It hasn't produced a lot" of activity so far, Scherrer said, "but it's still churning up new fields."

And even if AR 1339 passes quietly by, there're plenty more active regions coming around the bend. The sun is currently approaching what's known as solar maximum, the peak of our star's roughly 11-year cycle of magnetic activity.

(Related: "As Sun Storms Ramp Up, Electric Grid Braces for Impact.")

What's more, the sun isn't entirely governed by its cycles—sunspots, flares, and other eruptions can occur at any time.

On the sun, Scherrer said, "there's always some level of activity."

Also see "Sun Headed Into Hibernation, Solar Studies Predict" >>