1 of 13

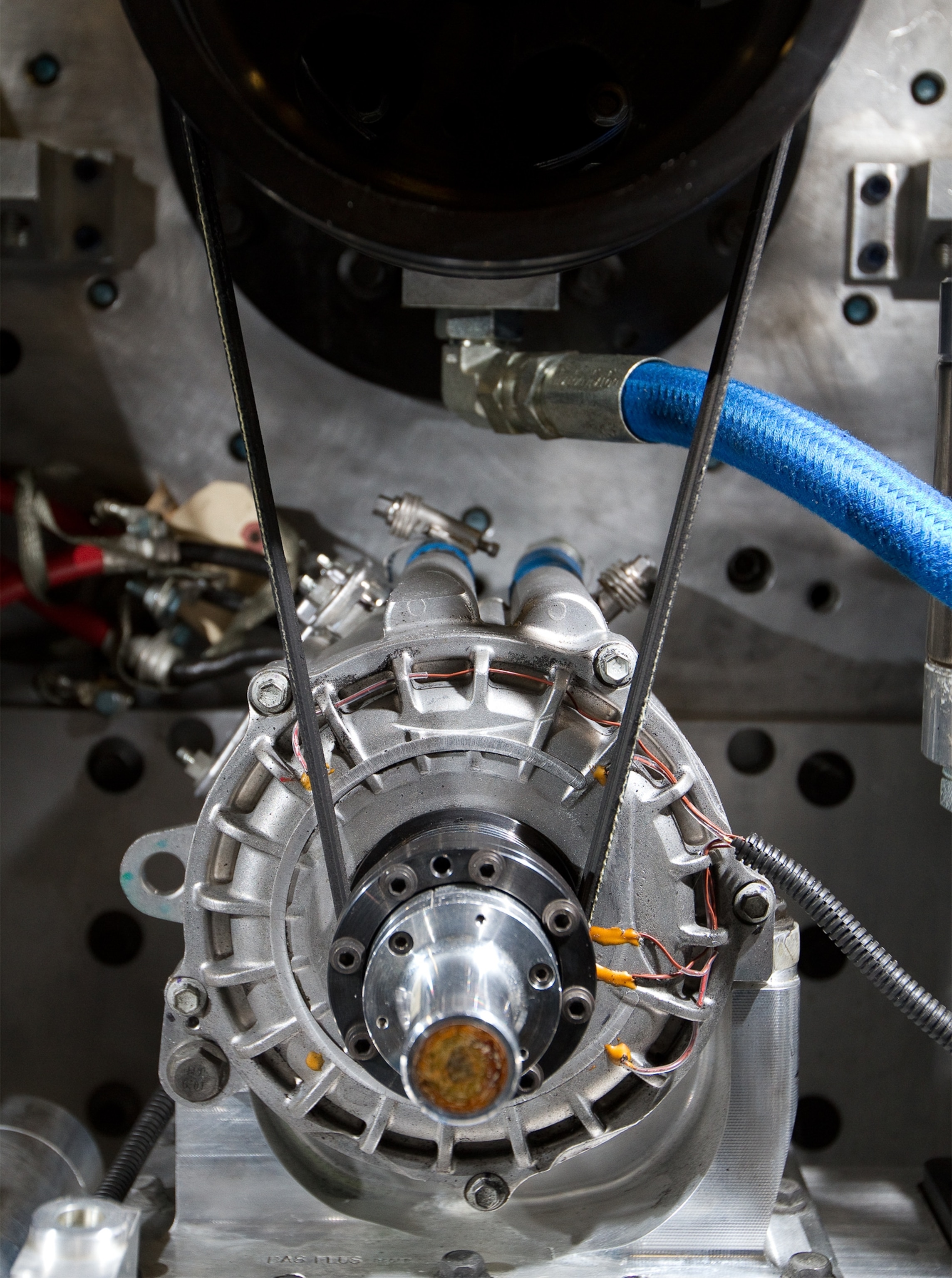

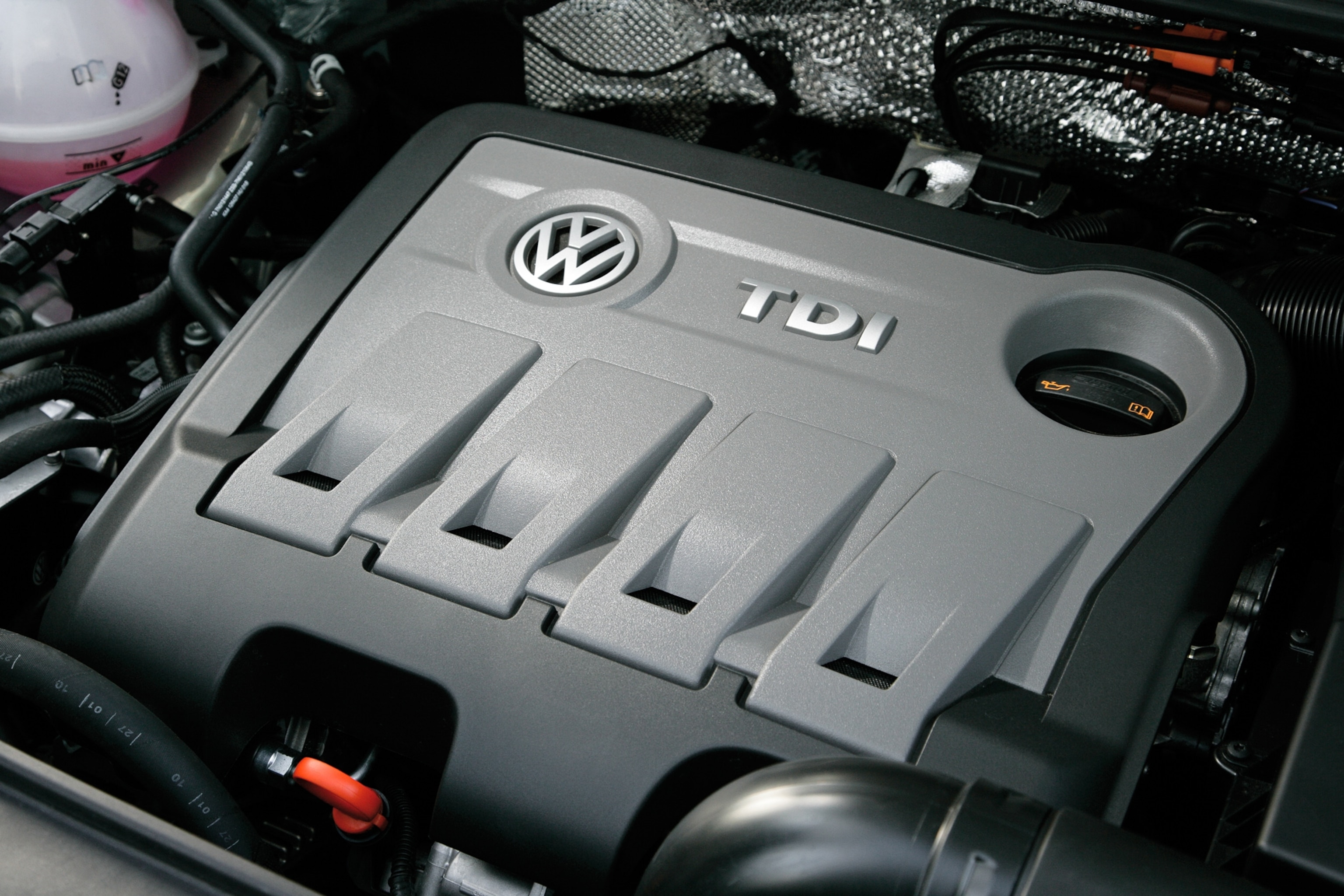

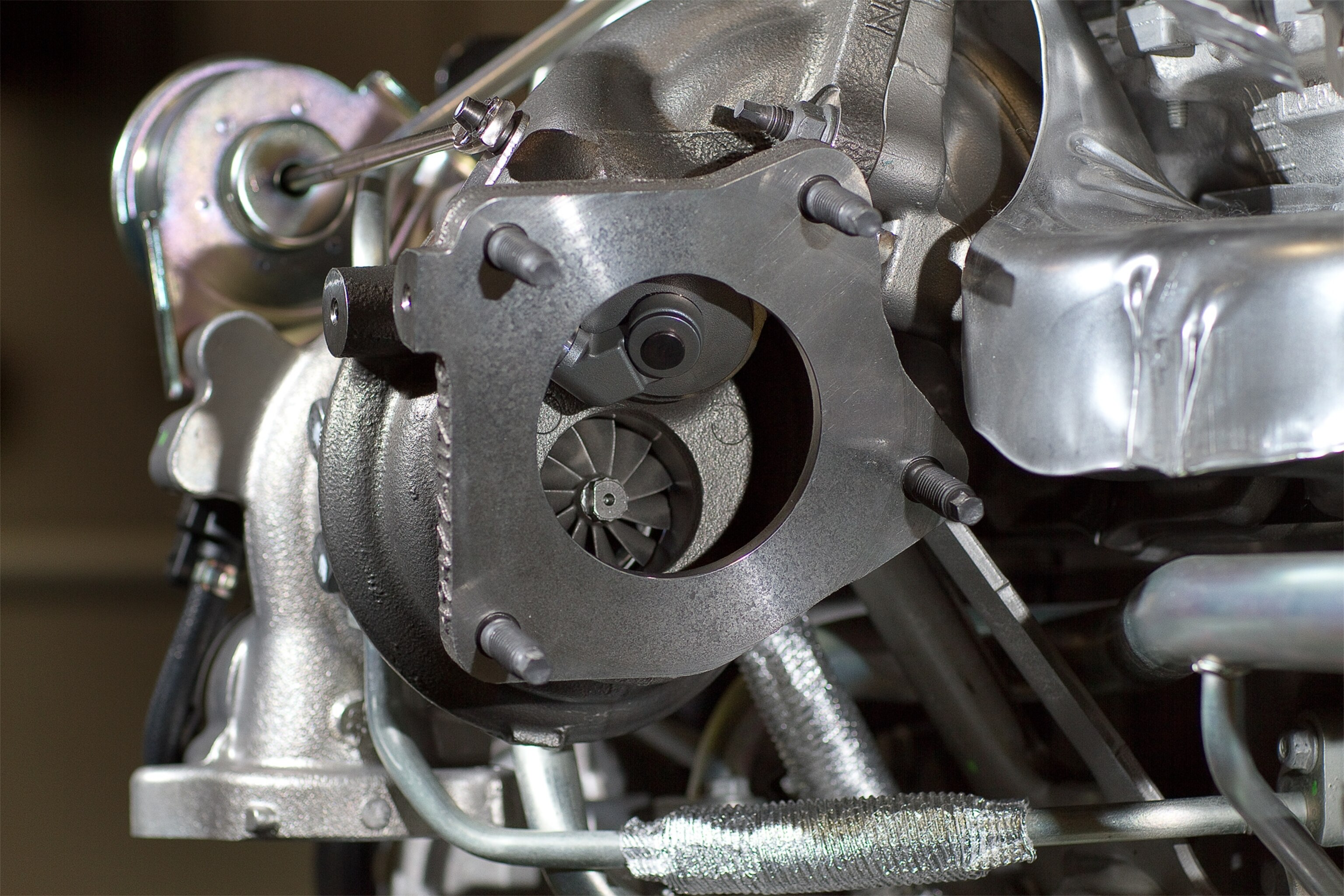

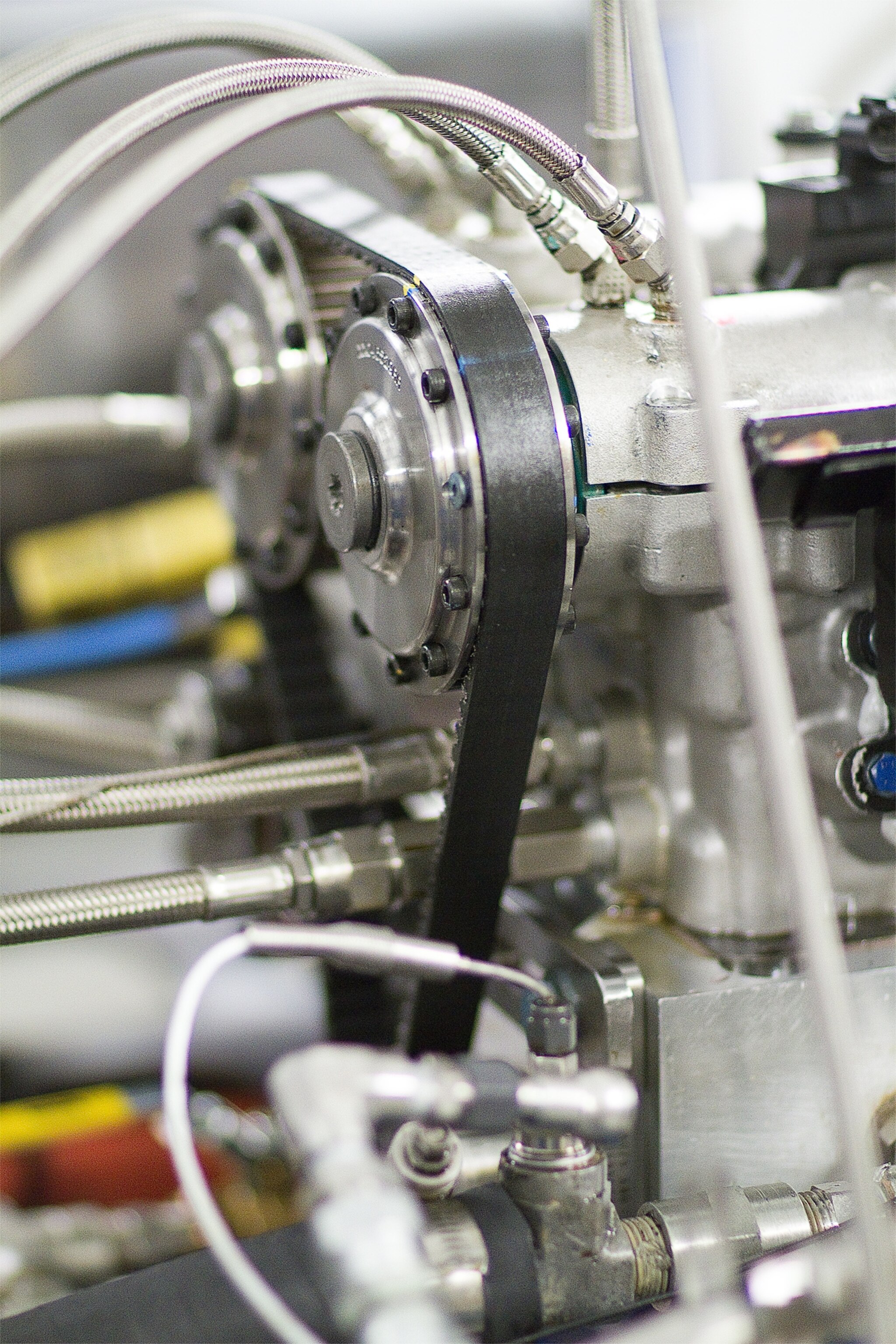

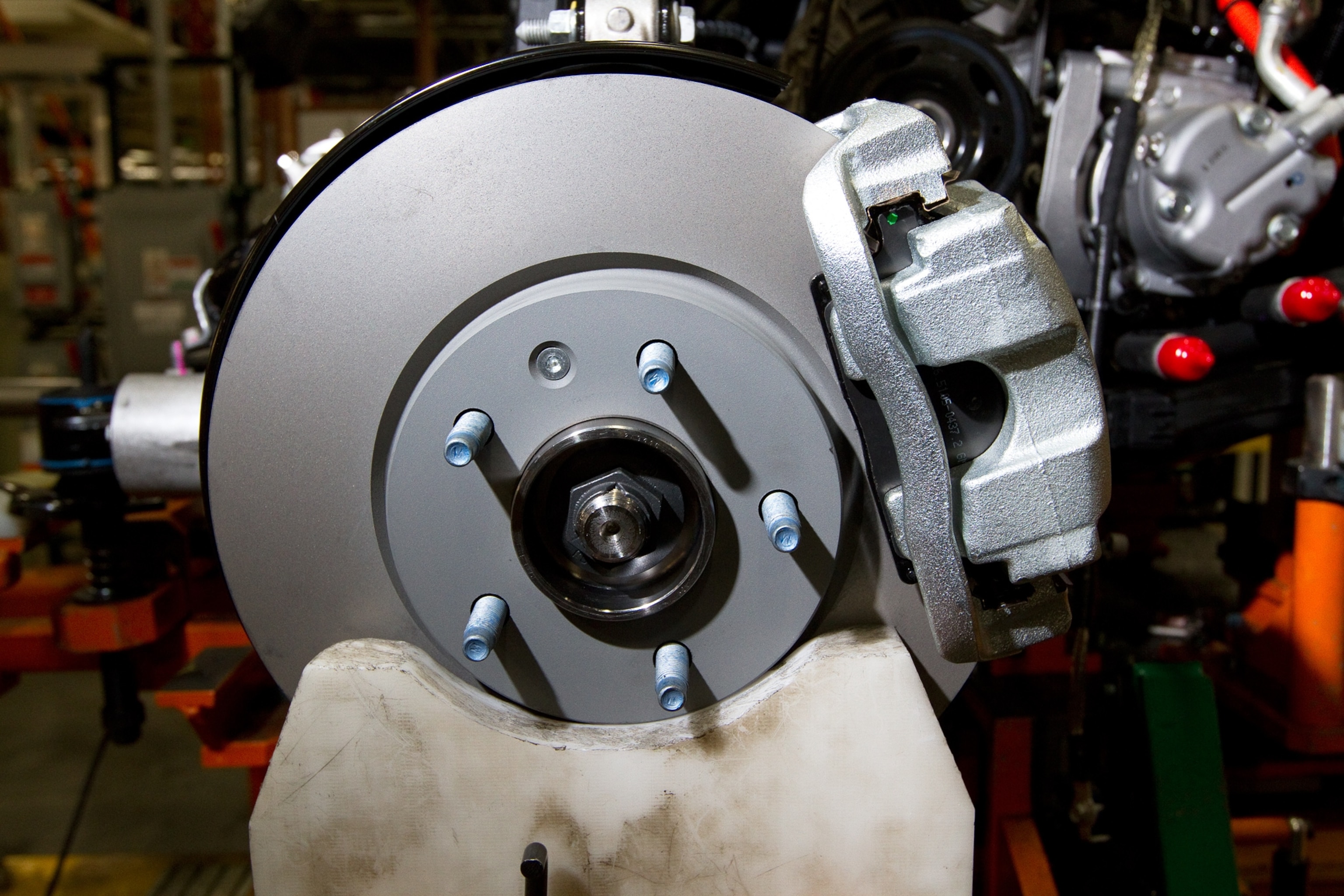

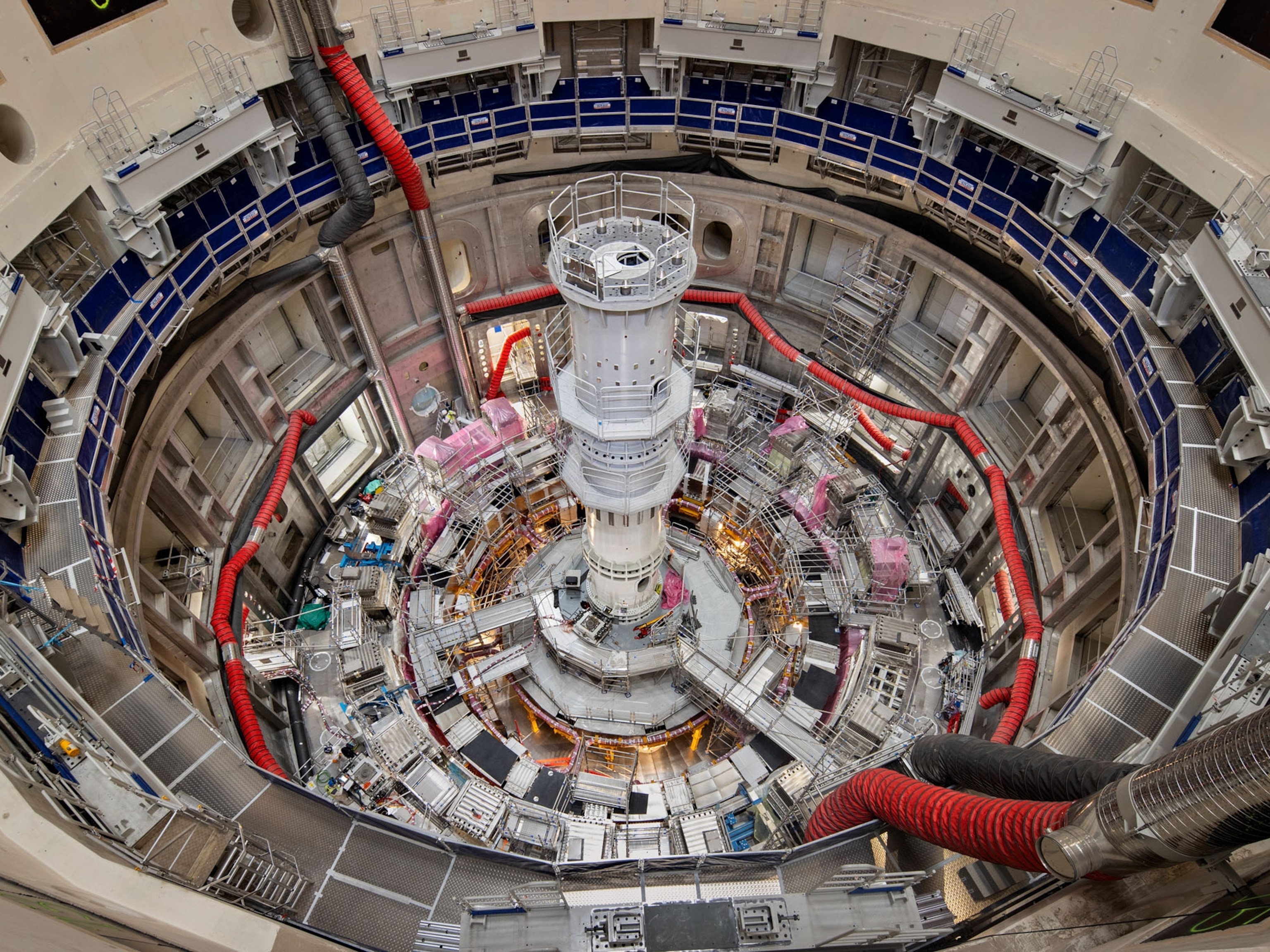

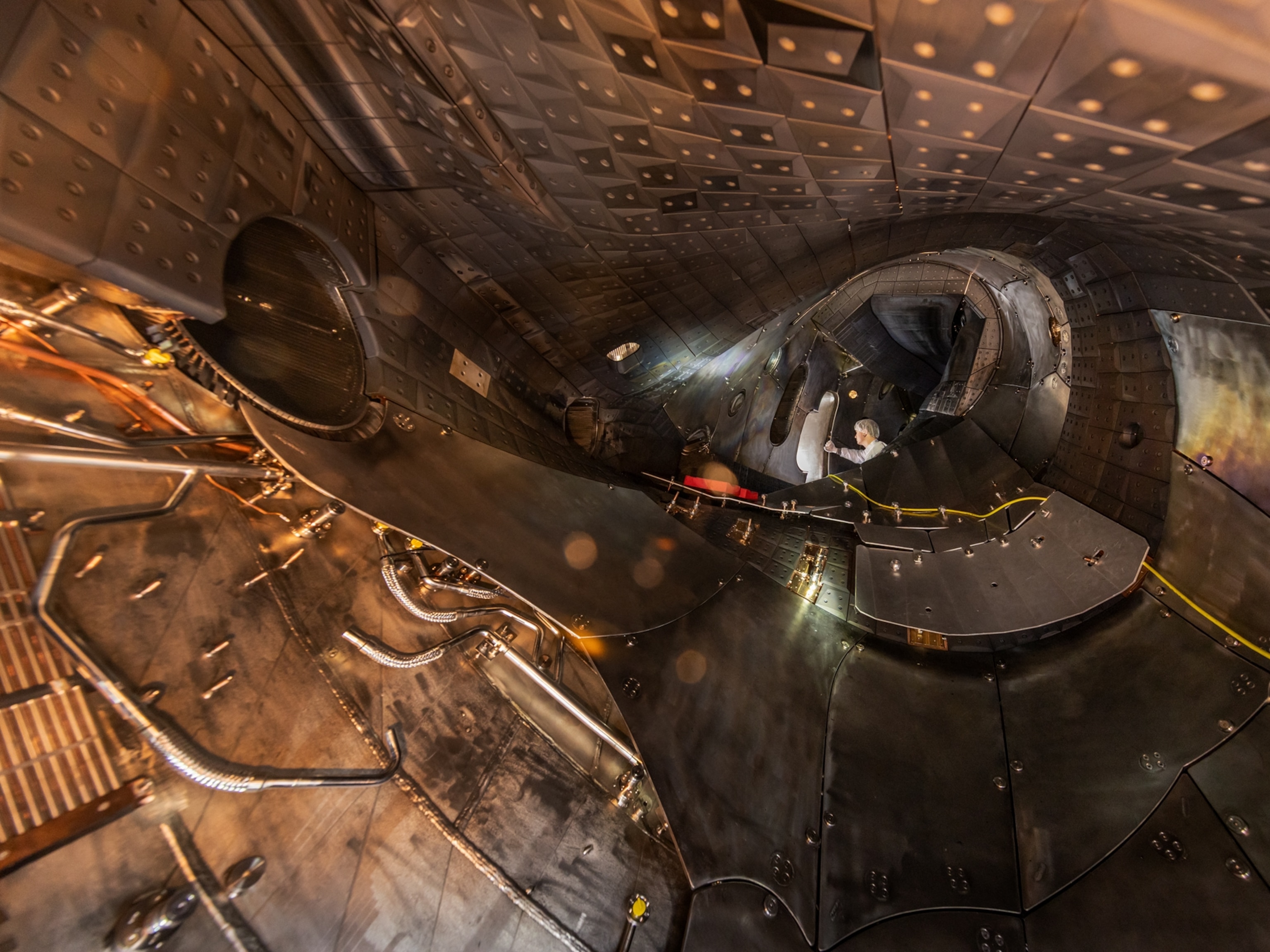

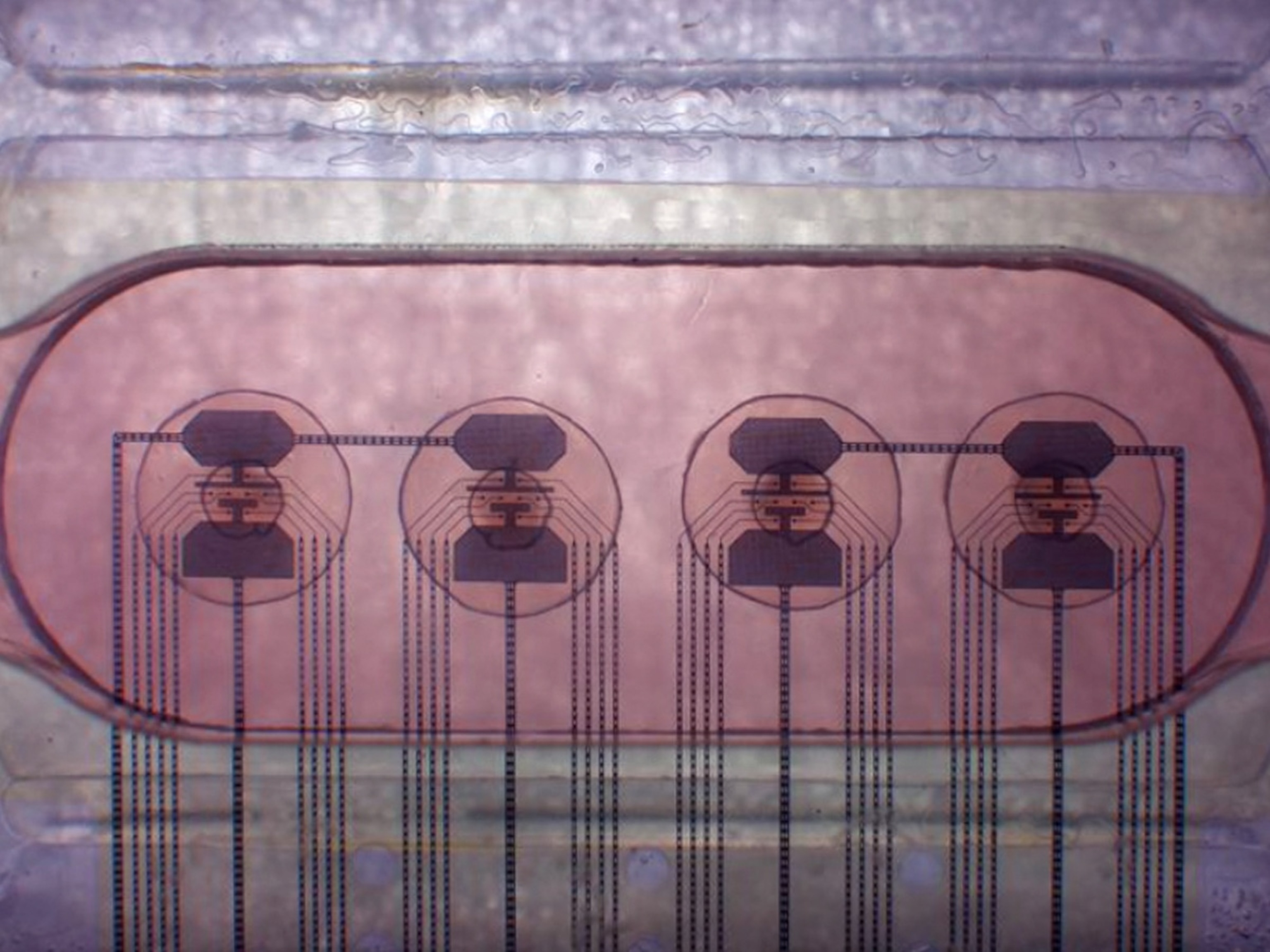

Photograph by Jeffrey Sauger, National Geographic

Pictures: A Rare Look Inside Carmakers’ Drive for 55 MPG

Automakers must dramatically improve fuel economy to meet new standards taking hold worldwide. They'll do it with smarter systems, sleeker profiles, better materials, and a healthy dose of electric power.

August 19, 2012