Saving Tasmania's Giant TreesPart of our weekly "In Focus" series—stepping back, looking closer. The Tasmanian parliament will soon vote on a comprehensive forest management plan which, if it passes, will protect nearly half a million acres of the island's wild forests. The agreement is seen as the best chance to end the heated three-decade dispute over control of the forests involving loggers, conservationists, and the state government. The plan includes details on the development of a sustainable timber industry while ensuring the permanent protection of some of the world's largest trees—the giants known as Eucalyptus regnant.In the Crown of a KingThe adrenaline is flowing, but it's not helping the weakness in my knees. I feel leaden and queasy when I look up at the tree's crown swaying impossibly high above me. With a frozen smile of terror, I clip into a climbing rope and begin "jugging" up the tree's trunk using mechanical ascenders. Below, the roots buttressing the enormous base stand out like the tendons on a wrestler's neck. Above, where bark has peeled away, the stovepipe-straight trunk is as smooth and white as sun-bleached bone.This behemoth was a sapling 500 years ago when Michelangelo painted the dome of the Sistine Chapel, an adolescent when the French revolutionaries stormed the Bastille. Today it soars nearly 300 feet (91 meters) above the forest floor, a living skyscraper; at 96 feet (29 meters), the main stem splits, sending two vast appendages another 18 stories skyward. The tree's scientific name, Eucalyptus regnans, means "ruling eucalyptus," and as I begin my ascent, I do feel as if I'm paying homage to a king.I'm about to join Steve Sillett (shown above), who's a pinprick in the tangled heights. Sillett, a professor in the forestry department at Humboldt State University in northern California, has dedicated his life to climbing the planet's biggest trees, called "titans." You can appreciate a titan from the ground, he says, but to really know it, you have to get up high.During the past 25 years he's helped improve roping techniques that have enabled him to safely reach the treetops of the five tallest species, and he has the distinction of being the first scientist to climb into the canopy of the tallest of the tall: California's redwoods. (Related: "Redwoods: The Super Trees—Making the Gatefold.") His expeditions have yielded groundbreaking data on the tallest tree species that have been published in dozens of scientific papers. Now, he's come to Tasmania's Florentine Valley with a team to add to that body of work by measuring the giant I'm jugging up. "You just wait till you're up there," he'd told me earlier, in less than scientific terms. "It's utter gnarl. You're going to freak!"About ten minutes into the climb, a cracking sound ricochets across the valley. I'm certain the limb holding my rope has snapped and I'm about to plummet to the ground. When I open my eyes, I discover that I'm still dangling in midair; it takes several minutes before my heart slows to a galloping pace. (Sillett tells me later that such noises occur when the tree flexes under its own weight, its huge branches grinding against one another.)Following Sillett's line, I reach the mid-crown, an immense candelabrum of glossy limbs 180 feet (55 meters) up, as high as the tallest trees in the Amazon. Sillett strolls nonchalantly out onto a branch no thicker than my forearm. He has the build of a stevedore and the hard features of a man accustomed to dominating his domain. I try to think of a penetrating question to ask, but I'm so tense that neither mind nor vocal chords are working. Sillett, however, needs no prompting: "This tree," he bursts out, "represents the maximum gnarliness, the maximum complexity, of the regnans. What a hulking beast!" he yells above the wind.With this one, Sillett has harpooned his Moby Dick.Only redwoods are taller (not by much) than Tasmania's eucalyptus trees, but, Sillett says, "Regnans is the fastest growing of them all—there's nothing that beats it to 300 feet." Also known as the mountain ash or swamp gum, Eucalyptus regnans puts all its energy into raising its seed-bearing crown above the fires that periodically tear through the Australian bush. This means growing at warp speed, which it does by shedding its bark to expose the surface of its trunk to photosynthesis. Although the rate slows substantially in older, taller trees, when a Regnans is young its vertical growth rate can be as much as 6.5 feet (2 meters) a year. "It cranks, recycling carbon dioxide and maximizing growth," Sillett explains. If an inferno rages through the forest before the crowns reach a safe height, the seeds are consumed, and the trees are lost. "It's all or nothing," he says. "You don't see this strategy anywhere else. There's no tree like it." (Related: "Giant Redwoods Grow Faster With Age.")These trees indeed are exceptional. They host dozens of species of plants, insects, and animals, including the protected wedge-tailed eagle. They're also among the most efficient of all trees at capturing carbon, which elevates them to global importance. In the Florentine Valley, 1,200 hectares (2,900 acres) of old-growth E. regnans can hold as much as 8.4 million tons of carbon dioxide—that's just shy of Tasmania's yearly CO2 emissions from human activity.Tree NerdsSillett raises a laser range finder to his eye and "shoots" the outermost leaves on the branch. "Distance, 7.2 meters!" he barks, adding more gently, "Did you get that, honey?" Reclining on the broad stump of a broken branch below is his wife and fellow Humboldt State scientist, Marie Antoine. (Eleven years ago they exchanged vows 310 feet [95 meters] in the air on ropes slung between two redwoods.) She is "keeping the book"—making detailed recordings of all the measurements of the tree. Marie Antoine nods and pencils the number in a journal.Also aloft are Robert Van Pelt, a research associate and lecturer at Humboldt State University, and three graduate students who have volunteered to spend their Christmas holiday with the team. Flitting through the crown like acrobatic tailors measuring the tree for a bespoke suit, the self-described tree nerds use tape measures and compasses as well as lasers to record the height, length, diameter, slope, and coordinates of every section of trunk and every branch.Snippets of the Bon Jovi song "Livin' on a Prayer" float down from above. Cameron Williams, one of the graduate students, has customized the lyrics: "Whoa, halfway there. . ." he sings. "Whoa!. . . It's windy up here! Take my data—we'll make it, I swear-ere!" Williams concedes that taking measurements all day in a wind-blasted tree is both mind-numbing and harrowing. "It's like being marooned on a desert island—desiccation, sunburn, and hypothermia are serious considerations." But, he adds quickly, "I wouldn't trade research climbing for anything.""When you're climbing a tree," Sillett muses, "there's this sense of vulnerability. You begin to appreciate something that's much greater than yourself, and you can't be the same person after that."As if confirming the thought, he lets loose a joyous yawp. He's discovered a bathtub-size pond in the stump of a broken limb. The wood of E. regnans trees is so susceptible to fungal decay that their trunks and branches are often partially hollow, and those cavities can hold hundreds of gallons of water—pools that are home to creatures such as nemertine worms and fly larvae. The hollows are used by mammals, birds, reptiles, and frogs for shelter and nesting, as well as a source of drinking water. Possums called sugar gliders den in them, benefiting on cold days from the heat produced by the decomposing wood.Van Pelt calls out to me, "There's a lot of myth about these trees, that they've stopped growing, that they're decadent and overmature and should be logged. In fact we're discovering the bigger and older they are, the more they're growing. They're growing like crazy!"Sillett points to woody capsules clustered beneath a pom-pom of leaves. Each capsule contains a dozen or more seeds. "I've never seen that kind of fecundity before," he says. "The tree is making an enormous investment in reproduction right now. It's more active than it has been in its whole 500-year life."A boyish impulse propels me to the very top of the crown where, suspended above the Florentine Valley, my thoughts begin to drift. Then I hear a roar. Out of nowhere a gale tears me from the trunk and wafts me over the abyss like a spider on a strand of silk. Panicking, I kick and paddle-wheel my arms. It's useless. I float, twisting in space, 260 feet (79 meters) above the ground. As fast as it blew in, the wind dies, and I swing back to the trunk and cling to it, grateful for its solidity. During that untethered moment I experienced a kind of self-forgetfulness. Watching the tree heaving and bucking around me, I imagined the tree not as an enormous mute object but as a sentient creature bellowing with indignation.Visualizing the TreeIt took Sillett's team three days to complete more than 10,000 individual measurements on the tree. Back at Humboldt State University, a computer program rendered the data into a 3-D model of the crown, making it possible to rotate and view the tree from different vantage points and navigate through the branches."That's all very nice for visualization," Sillett says, "but I hope the scientific information the team gathers will be useful to both industry and conservation. The models we build of tree crowns permit accurate calculations of tree surface areas and volumes as well as whole-tree estimates of leaf area, leaf mass, number of leaves. Our measurements can be used to estimate accurately a tree's total bark surface area, bark volume, sapwood volume, heartwood volume, and biomass. We can calculate rates of wood production."Such information, he says, allows scientists to appreciate for the first time just how fast these old giants are growing and how responsive they are to their environment. "Big old trees aren't just sitting there!" Sillett exclaims.Loggers and Conservationists Battle It OutEuropeans settled Tasmania just over 200 years ago. Ever since, swaths of old-growth eucalyptus have been felled, bulldozed, or dynamited to feed sawmills and, recently, wood-chip mills. By 2005 more than 3.5 million tons of wood chips (some from old-growth forests) were being exported from Tasmania annually, mostly to be made into products such as toilet paper. Today only a small percentage of the E. regnans trees alive in pre-European Tasmania are still standing.Mike Woods, a third-generation logger from the town of Triabunna, points out that after a forest "coup" (an area designated for logging) has been logged, the "slash" (the treetops and lateral branches that are left behind) is burned, and the resulting ash bed is sown with seeds collected from a variety of dominant species in the area. "The regrowth is as thick as the hair on a dog's back," Woods says.Ken Jeffreys, a spokesperson for Forestry Tasmania, the government body that manages the state's forests and regulates—and collects royalties from—the logging industry, points out that some 47 percent of Tasmania's land is protected within national parks and World Heritage areas. He says that the best form of forest management involves replicating nature. "Because eucalypt forest requires fire to regenerate, we also use fire. To get proper regeneration of wet eucalypt forest, you need to create an ash bed. We then take a helicopter and drop seeds we collected earlier onto that harvested coup. What that means is that the forest that comes back afterward mimics the forest that we harvested and contains all the biodiversity elements."David Lindenmayer, a leading forest scientist at Australian National University in Canberra, argues that it's "a gross oversimplification to say that just because you've regrown the dominant trees, it's actually sustainable. That's a deep misunderstanding of the concept."Lindenmayer points out that every time a native forest is cut, burned, and reseeded, the entire ecosystem loses biodiversity and complexity. Forestry Tasmania's burning of slash damages trees left standing during selective logging, making them poor habitat for tree-dwelling animals. Also, he says, the controlled burns destroy the understory and ground vegetation, further impoverishing the ecosystem."Essentially what you're doing is taking old forest and converting it to young forest that will never be allowed to be old forest again." (Regrown trees that reach about 90 years old can be logged.) "Nor will it ever have the characteristics that you need for biodiversity."Animals such as possums that nest only in hollow trees are particularly susceptible to the effects of logging. Their affinity with their nest trees is so strong that if their territory is logged, they typically stay there—and die—rather than move to adjacent forest.Protecting the GiantsThe standoff between loggers and conservationists reached a turning point in September 2010, when Tasmania's largest logging contractor,Gunns Ltd., ended its operations in native forests. Sustained campaigning by environmentalists played into the decision, but just as important were the plummeting world prices for wood chips.The Australian government agreed to compensate affected workers, and in 2011 Prime Minister Julia Gillard signed an agreement to provide "immediate interim" protection for more than a million acres of native forest, including rare stands of Eucalyptus regnans. The agreement was intended as a stay of execution while the viability of the proposed reserves and their impact on the much diminished logging industry were assessed; formal protection, which would permanently ban logging in the reserves, was to follow.But instead, in contravention of the agreement, logging operations in some of the most ecologically sensitive areas (though not in the Florentine Valley) were given the go-ahead by Forestry Tasmania, with the state and federal governments' approval.Whatever policy decisions end up being made about Tasmania's eucalyptus forests, one thing is certain: The tree Sillett and his team just spent days measuring cannot be cut down. Under Tasmania's rarely invoked Giant Trees policy, every tree measuring more than 85 meters (279 feet) tall or more than 280 cubic meters (366 cubic yards) in volume is protected. According to Sillett's model, the tree, at a whopping 391 cubic meters (511 cubic yards), is the world's largest known E. regnans by volume.The Giant Trees policy is "a start," says Brett Misfud, a schoolteacher from the Australian mainland who's been exploring forests for the past 20 years. "But what we really need is to protect the native forest around the big trees. Otherwise they'll be exposed to the wind and other elements, and they'll die just as surely as if they were logged."Outside North America, Mifsud has found more of the world's biggest trees than anyone else (well over 120). In Tasmania, he's located more than 60 giants. The day I spent with him in a valley south of Hobart, he found four Eucalyptus regnans that qualify for protection, including one with a girth of 21.6 meters (almost 71 feet)—big enough for 20 people to stand comfortably inside its hollow base."This is why we bushwhack," Mifsud says. "To save big trees, one by one, and hopefully everything in between."—Michael Davie

Photograph by Bill Hatcher, National Geographic

Pictures: Saving and Studying Tasmania's Giant Trees

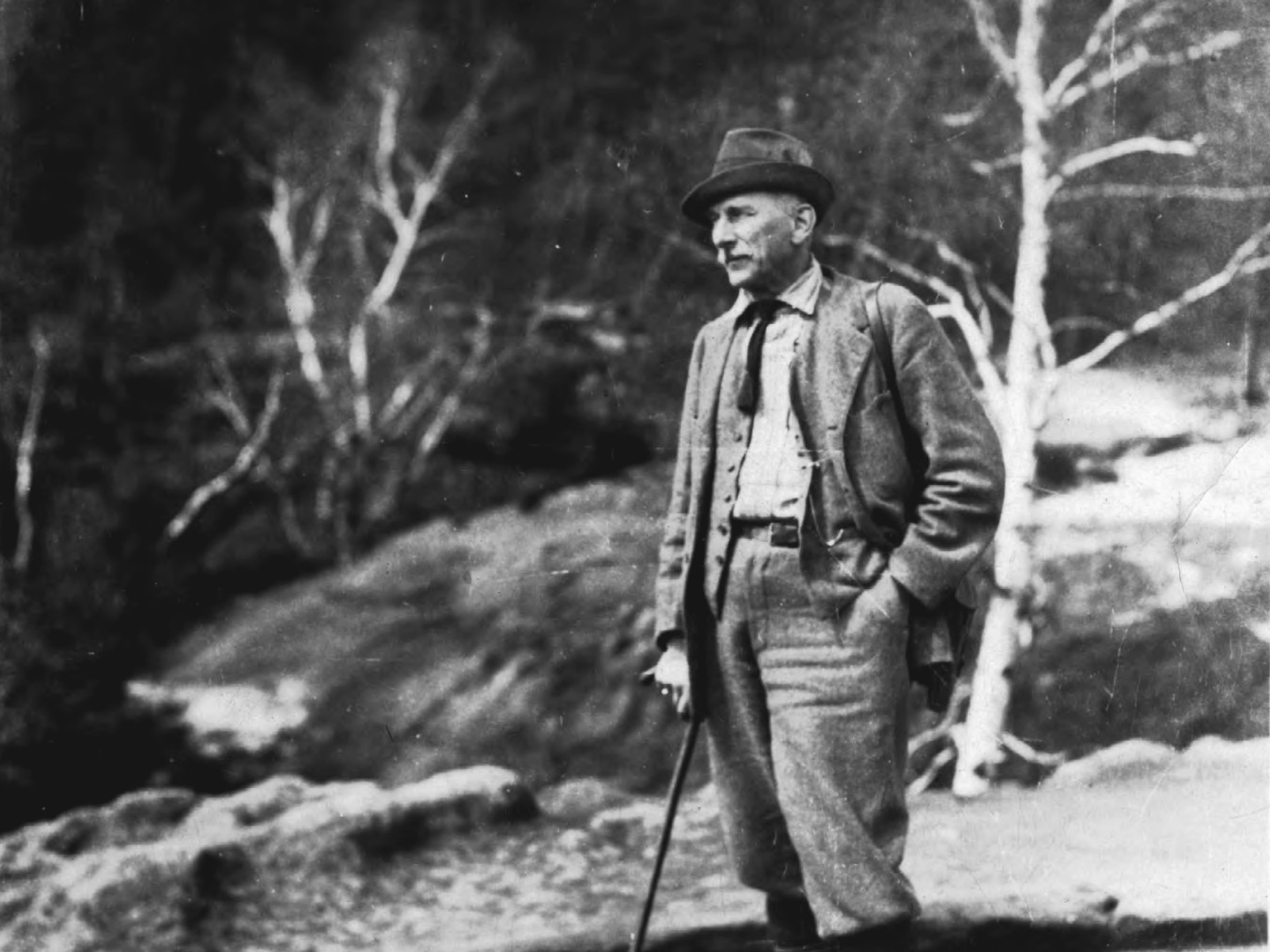

As Tasmania's parliament prepares to vote on increasing protections for its native forests, scientists study some of the largest trees in the world.

Published March 24, 2013