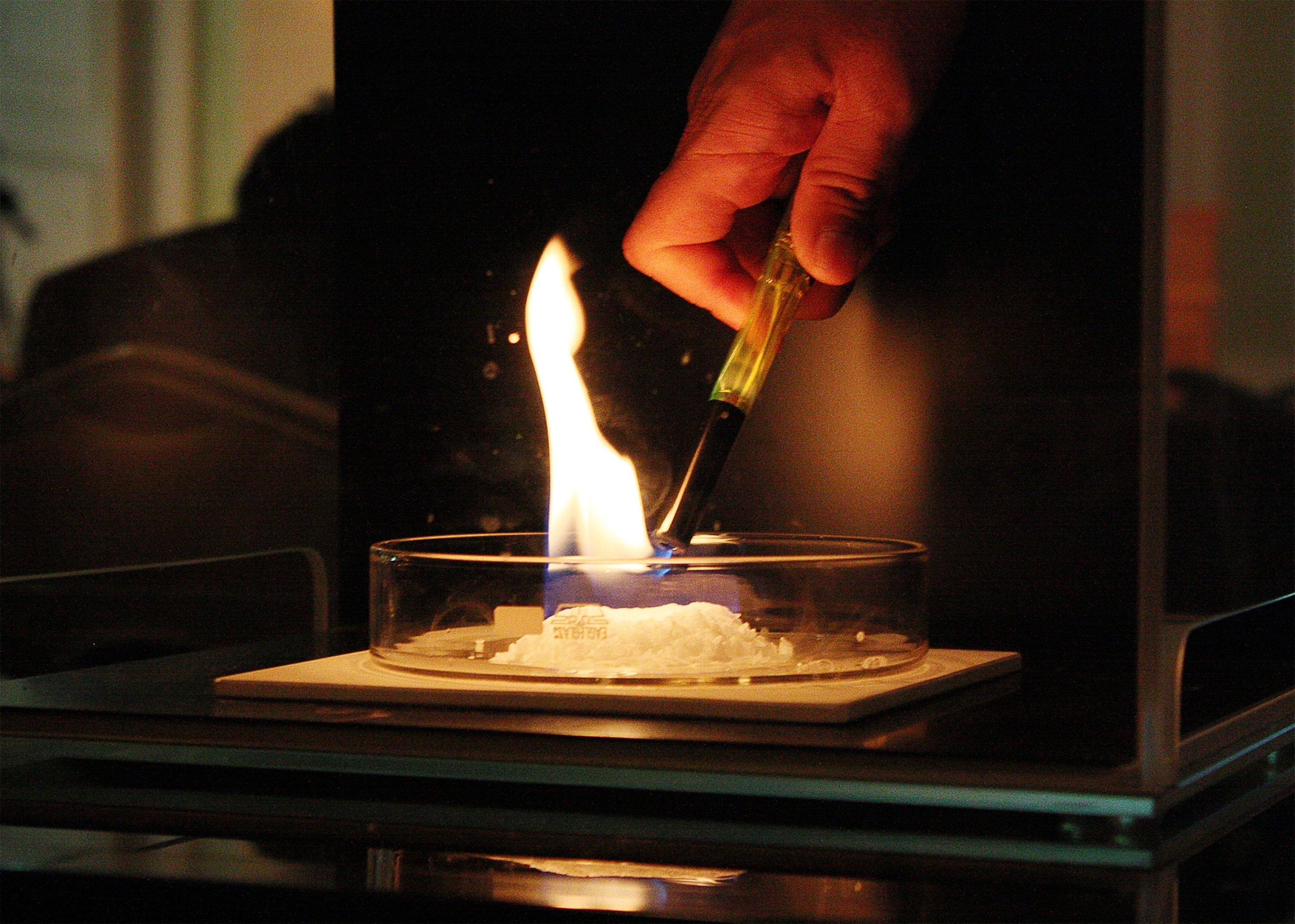

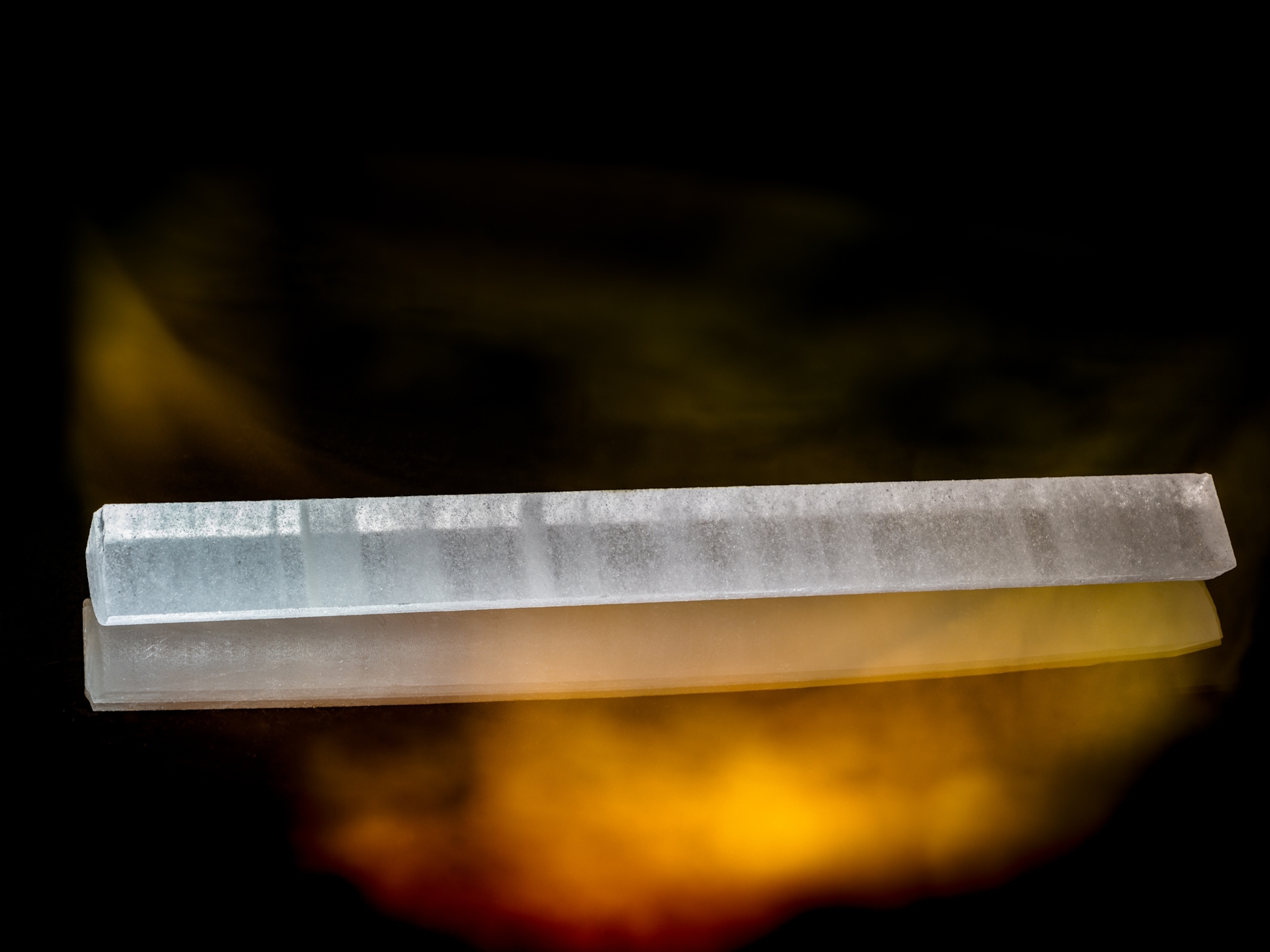

A flame ripples from a burner on the back of a deepwater drilling rig in the Pacific Ocean off the southern coast of Japan, heralding an energy breakthrough for a power-starved nation.Japan announced on March 12 that it had extracted natural gas at a depth of 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) from one of the most mysterious and vast reservoirs of fuel on Earth—methane hydrates, which are methane molecules trapped in ice crystals. The successful foray by the drill ship Chikyu marked the first time ever that natural gas had been produced from offshore methane hydrates, known as the "ice that burns." (See related quiz: "What You Don't Know About Natural Gas.") Japan hopes that the test extraction is just the first step in an effort aimed at bringing the fuel into commercial production within the next six years.

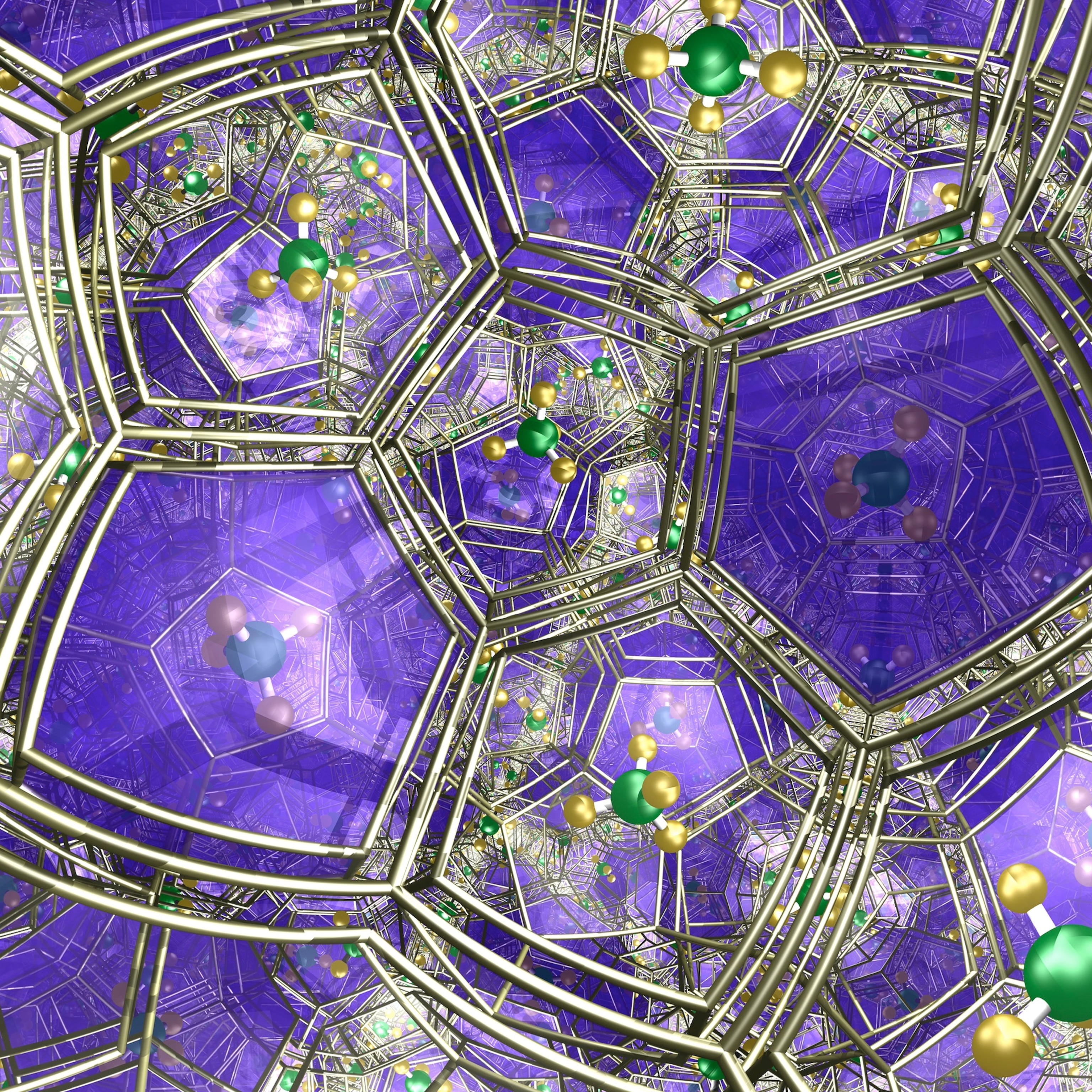

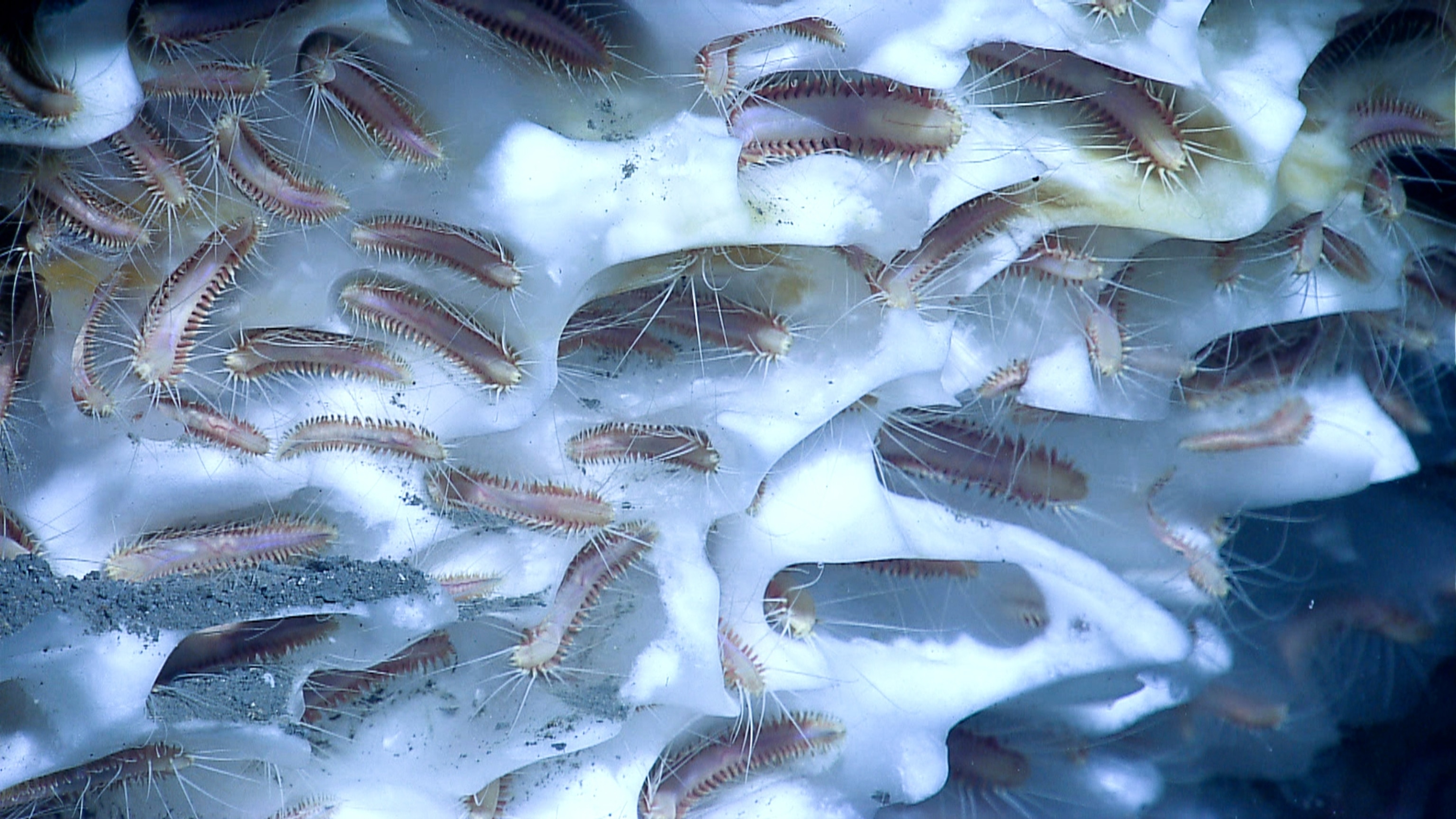

That's a far faster timetable than most researchers have foreseen, even though there is wide agreement that the methane hydrates buried beneath the seafloor on continental shelves and under the Arctic permafrost are likely the world's largest store of carbon-based fuel. The figure often cited, 700,000 trillion cubic feet of methane trapped in hydrates, is a staggering sum that would exceed the energy content of all oil, coal, and other natural gas reserves known on Earth. (See the U.S. Department of Energy's primer on methane hydrates.) But under high pressure and at low temperatures, the methane molecules are locked in lattice-like cages of frozen water—a kind of host/guest relationship called a "clathrate."

Because methane is a gas with high global-warming potential—25 times more potent than carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere—there is great concern over uncontrolled release of the methane from hydrate formations. Yet methane also can help cut carbon emissions when it is burned instead of coal for electricity. (See related: "Good Gas, Bad Gas.") The U.S. government, which has a major methane hydrate research program, last year even sought to test a method for extracting methane and sequestering carbon dioxide at the same time.

But perhaps no nation has conducted as much methane hydrate research as Japan, which until now has had virtually no exploitable domestic fossil fuel resources. The nation's reliance on foreign gas imports has surged since the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi disaster, which has led to the idling of nearly all 54 nuclear power plants that once provided 30 percent of Japan's energy. (See related: "One Year After Fukushima, Japan Faces Shortages of Energy, Trust.") In light of the nation's energy woes, the methane hydrate milestone 50 miles (80 kilometers) off the coast of Aichi Prefecture in central Japan was especially significant. "Japan could finally have an energy source to call its own, " said Takami Kawamoto, spokesman for the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC).

—Marianne Lavelle, with additional reporting from Brad ScriberThis story is part of a special series that explores energy issues. For more, visit The Great Energy Challenge.