Behind the Cover: July 2013

The moon's birth may have been the worst catastrophe in Earth's history.

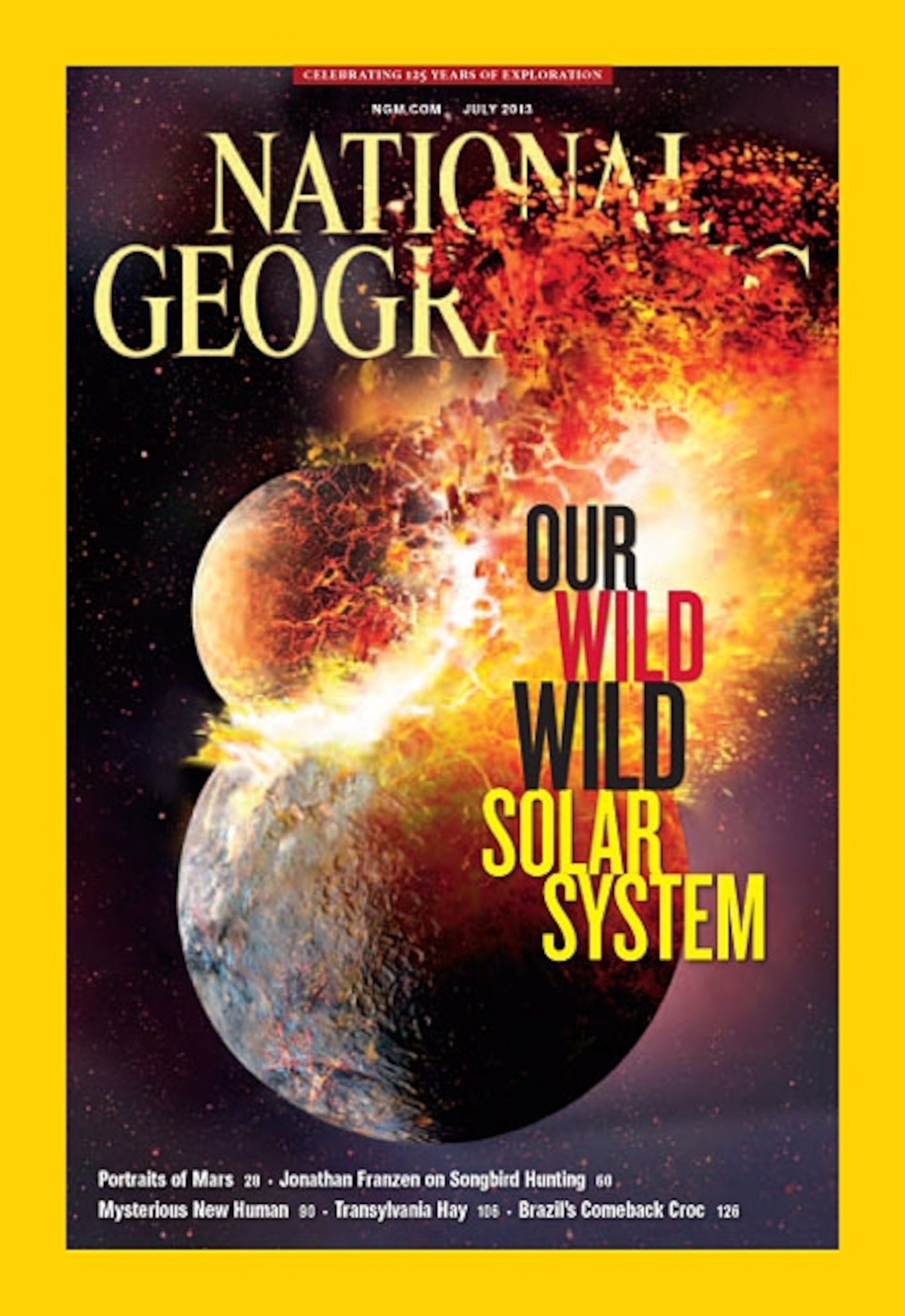

The July cover of National Geographic depicts a body the size of Mars slamming into the newborn planet Earth some 4.5 billion years ago. A cosmic crash like this, according to a now widely accepted theory, blasted molten rock far into space and spawned something familiar: our moon, creator of tides.

The task of illustrating this seminal event in our planet's history fell to space artist Dana Berry. Years ago Berry had imagined a collision between two ultradense neutron stars, but depicting the moon's birth was a new challenge. "You don't think of the violence involved in the formation of something as tranquil and serene as the moon," he said. "It was an apocalypse."

To capture that cataclysm in a scientifically accurate way, Berry shared drafts of his artwork with two senior scientists who developed and refined the so-called giant impact model: William K. Hartmann of the Planetary Science Institute and Robin Canup of the Southwest Research Institute. Their research suggests that the rogue body struck Earth with a glancing blow, spraying melted slabs of the planet sideways into orbit.

Berry, whose work has graced three previous National Geographic magazine covers, studied detailed images of water and other fluids splashing in "mid-flight" after such impacts. He rendered the two colliding planets and their cratered surfaces with a 3-D animation program called Maya. He then moved the artwork into Adobe Photoshop to add cracks, shards, and the impression of Earth's crust peeling off violently.

But the image still lacked the texture Berry desired to make the explosion of fiery rock look realistic. So he resorted to old-school painting: He splattered black ink across large art paper, Jackson Pollock-style, and scanned the pattern into his computer. Melding this layer with his artwork in Photoshop did the trick.

"This is so far beyond human experience," said Berry. "There's no way to comprehend what it actually looked like." For now, though, the cover represents the best bet of scientists.