How (And Why) to Build a Dune

In one Jersey Shore community, the sand stood up to Sandy.

A dune in the right place at the right time is a very powerful thing. More than just hills of sand, dunes can be a beach town's first line of defense against storms and erosion. That's why some coastal communities are encouraging their growth.

South Seaside Park, New Jersey — When Superstorm Sandy hit the Jersey Shore in October 2012, the ocean surged onto land on the strength of winds blowing at up to 89 miles (143 kilometers) per hour. Some towns had no barriers between the ocean and their homes, businesses, and boardwalks. But those that did—those that had dunes—well, just look at Midway Beach.

(Related article: "After Sandy: The Future of Boardwalks.")

At first glance, it doesn't seem like the kind of town that could have survived such a powerful storm. It's a quarter-mile-long community within South Seaside Park, New Jersey, made up almost entirely of post-World War II, one-story bungalows. To its north, Sandy knocked a roller coaster into the ocean. To its south, ocean water crossed over the barrier island and into Barnegat Bay.

But only one home in Midway Beach saw any water damage.

One big reason for that—or, rather, one tall reason: Midway is protected by 25-foot-high (7.6-meter-high) dunes that the community started passively building 30 years ago.

The project started as a way to prevent an annual annoyance, explains Dominick Solazzo, a trustee on the Midway Beach Condominium Association's board of directors.

Without fencing, the sand would blow into their community, so why not try to keep it on the beach?

"The thought was: 'Let's put in storm fences so we don't have to backhoe the sand every spring," says Solazzo. A union electrician, he has a B.S. in natural resource management from Rutgers University and lives in Midway year-round.

That first fence was installed in the 1980s, and the dunes grew from there. For the last five years, Solazzo has led a resident-driven, volunteer effort to more actively manage the dune growth, a project that Stewart Farrell, director of the Richard Stockton Coastal Research Center, calls "the most dynamic 'bootstrap' dune project on the coast."

Before Superstorm Sandy, the dunes were 25 feet (7.6 meters) high and 120 to 150 feet (36 to 45 meters) wide. Sandy snatched about 50 feet (15 meters) of sand from that width, so in November, right after the storm, the Midway Beach Condominium Association spent $7,000 on plants and fencing to start replacing the sand without using bulldozers. Here's what they did.

1. Use plants as anchors.

Plants help keep the sand in place. Solazzo estimates that Midway's dunes host some 60,000 beach plants, mostlyAmerican beach grass, which provides several benefits. Its roots are shallow and they spread wide, so the grass doesn't need to cover the dune entirely to be effective. And as the sand piles high, it grows upward but leaves its roots behind, creating layers in the sand.

It also doesn't ask for much.

"American beach grass sucks most of its nutrients-nitrogen especially-out of the atmosphere, so it doesn't need soil to get started," says Farrell. As the grass ages and starts to create leaf litter, other plants can grow in that organic material-plants like bayberry and seaside goldenrod-though that process can take 15 to 20 years.

Last winter, Midway also accepted donations of cast-off Christmas trees to intersperse with the fencing and act as additional anchors for the sand.

"The fencing, the roots, the Christmas trees-what rebar is to concrete, that is to this dune," Solazzo says. "They allow this to act as a system instead of a giant pile of sand that will blow away."

2. Install a fence, and let the wind do the heavy lifting.

But not just any fence.

The first kind used at Midway, Solazzo says, was chain-link fence, which didn't quite work. Too much sand blew through the gaps.

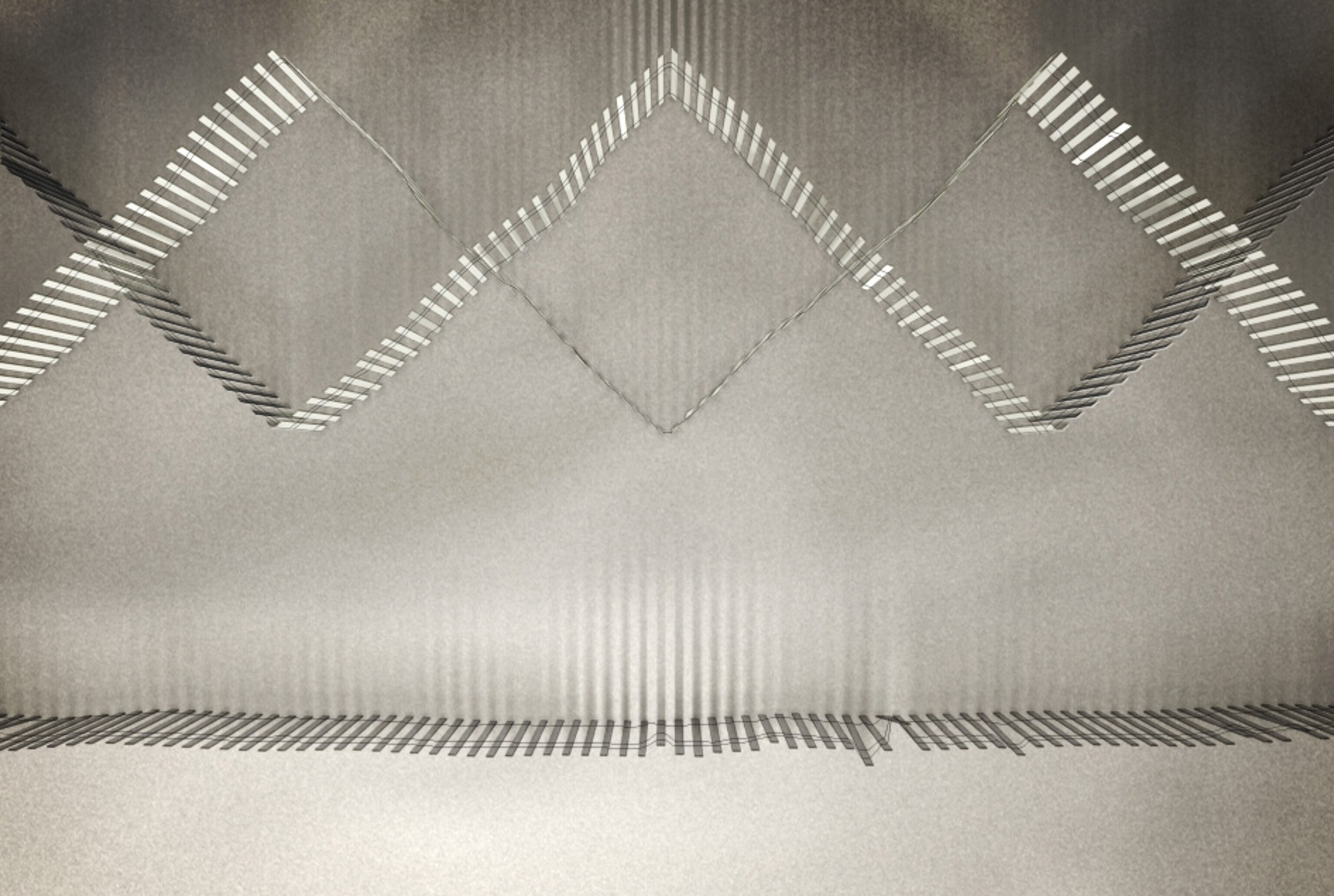

Instead, Midway used four-foot-high, wood-slatted fencing to limit the velocity of the wind. It isn't sand-proof, either, so they installed two layers in a repeating sawtooth pattern.

The angles of the fence aren't parallel to the shoreline, but instead are perpendicular to the direction of the winds. One side captures sand from the northeast-the way the winds typically blow in fall and winter-and the other intersects the less powerful but still frequent southeast winds.

The pattern is repeated up the dune, so swirling sand has several chances to be caught by slats of wood before reaching the homes on the other side.

Right now, there's an additional fence parallel to the shoreline, but that's more to keep nosy tourists out of the dunes, where they might step on and damage plant roots, says Solazzo. It'll be taken down at the end of the summer season.

(Related: See aerial photos of desert sand dunes.)

There's no need for bulldozers or shovels when the wind does the work of building the dune, and Farrell says that's better for the beach grass too. Adding compacted sand to the dunes would hamper its growth. "The center of the plant is a spiral, and it unfurls like a flag upward," he says. "If you bury it with windblown sand, the plant simply keeps growing up through the dry sand, and it leaves behind a string going all the way back down to where it started."

3. Repeat.

Solazzo expects that 90 percent of the fencing will be buried in sand by next spring, making up for a lot of what Sandy took away. "We'll plant more plants then," he says.

As Solazzo and I talked by the dune, a woman in a purple strapless bikini top and white shorts walked past, headed home after a day at the beach. She told me that her parents lived in one of the Midway bungalows, and that the dunes had saved her family's home.

"Thank God," she said, waving her hand at those piles of sand.

(Related article: "New Map Shows Where Nature Protects U.S. Coast".)