Why Are Corpse-Eating Beetles Being Released Into the Wild?

Scientists working to bring back the mysteriously declining American burying beetle.

Four-day-old chicken or quail left to rot in the sun? Check. Shovel? Sure. A good hole that can house beetles? Yup.

Listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and as critically endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species, this 1.5- to 2-inch (4- to 5-centimeter) insect has been disappearing from across the United States since about the early 1900s.

"No one knows why," said Scott Hamilton, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in Missouri.

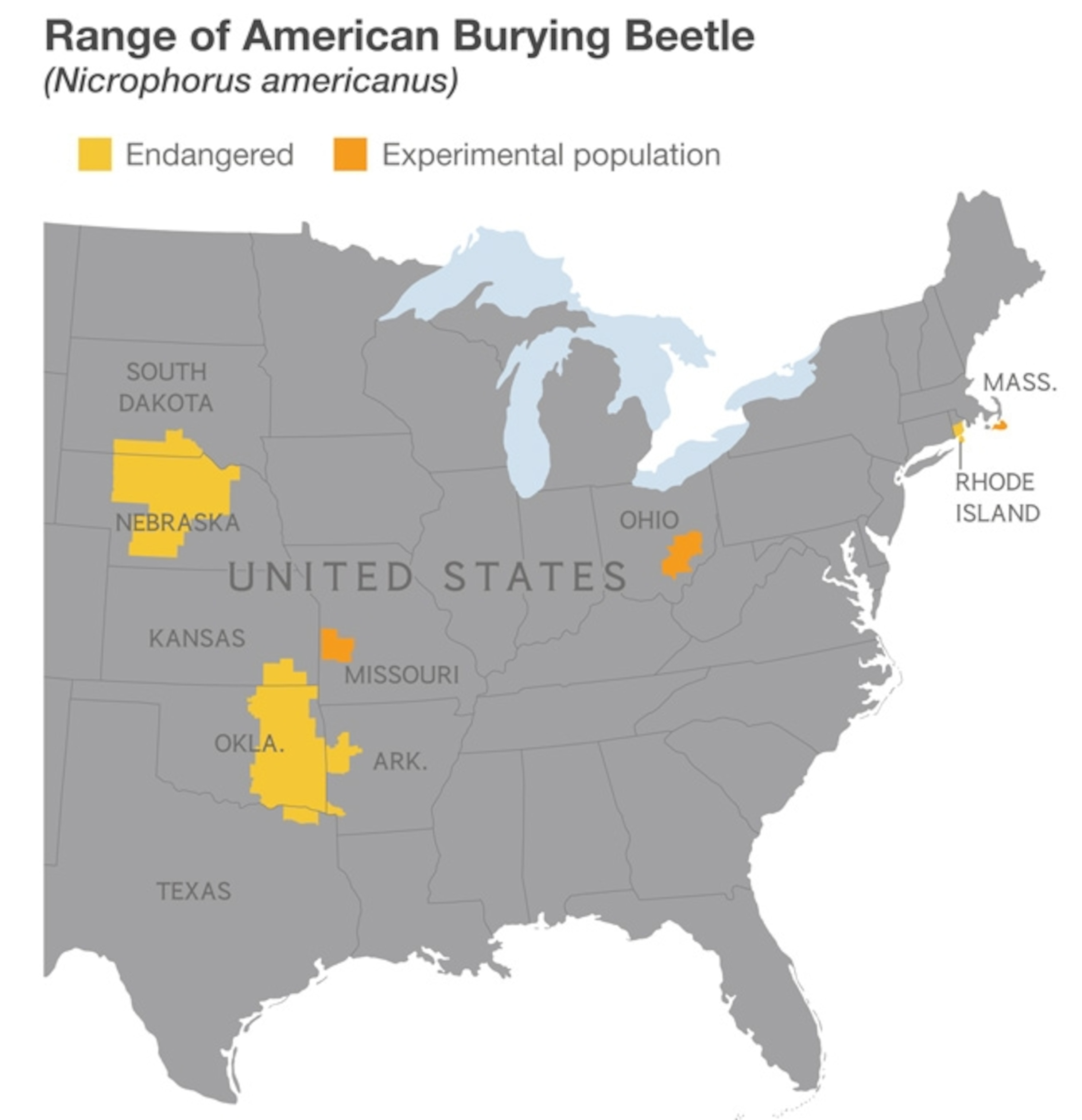

The splotchy orange beetle used to roam 35 states, but at the time of its USFWS listing in 1989, the only known wild population left was ensconced in Rhode Island.

Subsequent searches uncovered American burying beetles in five other states—Arkansas, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and South Dakota.

Researchers have suggested all kinds of explanations for this vanishing act. They range from increasing light pollution—the beetles are nocturnal—to the pesticide DDT to a changing constellation of fellow scavengers gunning for the same carcasses.

Some experts have even suggested that the demise of the passenger pigeon, which was the ideal carrion size for the beetles, in the early 1900s has driven the decline.

Seeing the Light

"[One] theory that holds a bit of water is light pollution," said Bob Merz, director of the Center for American Burying Beetle Conservation at the Saint Louis Zoo in Missouri.

"They're the only purely nocturnal species in the whole genus of burying beetles," said Merz. The genus includes 68 species. And certain studies have shown that some common types of human lighting can disorient beetles preparing to breed. (Watch a National Geographic video of burying beetles at work.)

When it's time to mate and lay eggs, burying beetle pairs will prepare a carcass for their future young.

That usually involves stripping the fur, feathers, or scales off a carcass that weighs 3.5 to 7 ounces (100 to 200 grams)—about the size of a passenger pigeon or a bobwhite quail—and covering it in antifungal and antibacterial secretions. "They form it into a meatball, basically," Merz said.

Then the beetles bury the carcass in about 9 inches (22 centimeters) of soil. Some enterprising couples will dig a hole several feet down to deposit their ball of dead flesh.

The female beetle then lays her eggs right next to the carcass. When the babies hatch, the parents feed them pieces of the "meatball."

But studies have shown that some of the burying beetles exposed to light at night either don't prepare the carcass or halfway prepare it, lay eggs on it, and then wander off, leaving their young to fend for themselves, explained Merz. (See beautiful pictures of insect eggs in National Geographic magazine.)

Good Parenting

Abandonment of young beetles could be problematic for the population as a whole, since they depend on their parents for about 14 days after they hatch.

American burying beetles exhibit "some of the highest levels of biparental care you'll see in the insect world," noted Lou Perrotti, director of conservation programs at the Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence, Rhode Island, and species survival plan coordinator for the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

In addition to preparing and burying a suitable carcass, the parent beetles must chew and process food for their young, regurgitating flesh for the larvae much like birds do with their chicks, explained the Saint Louis Zoo's Merz.

The parents will even call to their young when it's mealtime by rubbing their abdomens against the insides of their wing shells to produce a kind of squeaking noise, he said.

American burying beetles live for only about a season, or three to four months, said Merz. He's seen one live to about 300 days in captivity, but that's the exception rather than the rule.

That's why continual births of new beetles are necessary to keep populations alive.

Not Enough Carcasses

Conservation and reintroduction programs—such as ones in Missouri and Ohio, and one off the coast of Massachusetts on Nantucket Island—are hoping to boost beetle numbers and learn as much as they can about this secretive insect and why it's declining. (Also see "Endangered Beetle Lies in Keystone XL Path.")

The Nantucket program is perhaps the furthest along. The last recorded sighting of an American burying beetle on the island was in the late 1920s, said Roger Williams Park Zoo's Perrotti.

But by taking a small group of American burying beetles from Block Island, off the coast of Rhode Island—the only naturally occurring population east of the Mississippi—staff at the zoo bred about 5,000 beetles as part of a reintroduction project.

Between 1994 and 2006, the team released about 3,000 beetles on the eastern and western sides of Nantucket Island in grassy areas.

Then, in 2006, they began a five-year provisioning and monitoring project to see if the reintroduced beetles would make it.

As part of that research, the scientists trapped beetles in early spring and summer by burying plastic containers and baiting them with rotting quail.

If these smelly traps caught American burying beetles, researchers marked the insects, weighed them, paired them up with a mate, and then released them again.

Researchers placed every pair in their own brood chamber and gave them a quail carcass to encourage them to lay eggs. (Get National Geographic's insect-egg desktop wallpaper.)

The scientists found anywhere between 8 and 140 pairs per year, said Perrotti. "We were seeing our population numbers start to grow," he said.

Then, in 2011, the team decided to stop giving carcasses to every beetle pair to see if there was enough naturally occurring carrion on the island to sustain the insects.

The results weren't promising: Project members provided dead quail to only 25 beetle pairs in 2011, resulting in a drop in population numbers by almost half the next year. In 2012 the team gave dead quail to another 25 beetle pairs, but saw their population numbers drop even further.

"I think we can safely say there's not enough available carrion to keep the numbers we [previously] established," Perrotti noted. "That carrion resource is paramount to this species' survival."

Perrotti and colleagues hope to see the beetle population numbers level out, but for now, the project is in a wait-and-see mode.

Biblical Roadblocks

Some reintroduction efforts on the mainland, like the project in Missouri's Wah'Kon-Tah Prairie on the Osage Plains, are just getting off the ground. (See prairie pictures.)

The Missouri reintroduction—led by a group that includes the Saint Louis Zoo and the USFWS—is only two years old and has already run into snags of a biblical nature.

Their first reintroduction, in June 2012, occurred during record drought conditions. The team released 236 beetles-or 118 beetle pairs. A check of a third of the brood chambers ten days after they released the beetle parents turned up 395 larvae.

However, when the team checked on the population after the breeding season, they captured only three new adult beetles.

They released another 600 beetles in June 2013, but the next day, the Wah'Kon-Tah area got hit with flood-inducing rains. "We had two inches [five centimeters] of rain in about two hours," said Hamilton, the USFWS lead for the Missouri reintroduction.

When Hamilton and some zoo staff went to check on the beetles they had buried the day before, the chambers were flooded.

"We had beetles crawling out to avoid drowning," he remembers.

When they checked the holes for the presence of beetle grubs, they only found five. "There should be about 10 to 15 grubs per chamber," Hamilton said.

Yet somehow, enough beetles made it through the rains to produce the next generation.

When Hamilton and colleagues trapped for beetles in late August, they caught 15 new adult beetles-more than they found the previous year.

"I thought [the flooding] was just going to devastate our efforts," said Hamilton. "[But] perhaps the beetles that escaped a watery grave went and paired up and found some carrion to raise their young."

Within Our Lifetime

Hamilton and colleagues plan to soldier on with their reintroduction efforts for five years. They'd like to see their beetle population grow to about a thousand in the Missouri prairie.

The Saint Louis Zoo's Merz marvels at how far the zoo's program has come.

A chance encounter with a dead bird and a related species, the margined burying beetle (Nicrophorus marginatus) on the zoo's grounds in the late 1990s inspired his work to help the American burying beetle, whose underground, nocturnal lifestyle can make it hard to find and study.

Merz and colleagues at the zoo started reading up on burying beetles, and "we found that there was a federally endangered [beetle species] that had once been in our state," he said.

So, in 2000 and 2001, the zoo staff decided to see if there were any American burying beetles left in Missouri.

"All the keepers went out around the state and looked for them, [but] we weren't finding any," Merz said.

That's really the heart of what drives the conservation efforts around the country led by Merz and Hamilton, among others.

"It was here," Merz said. "[The beetle] was in my ecosystem within my lifetime, and now it's gone."

Follow Jane J. Lee on Twitter.