Lady in WaitingOn October 29, 2012, superstorm Sandy barreled toward New York City. Liberty and Ellis Islands, two relatively tiny pieces of land huddled together in the city's harbor, were dangerously exposed.

That's the peril of being American icons sitting in New York Harbor. It makes them beacons. It also makes them vulnerable.

The National Park Service team responsible for the joint monument had battened down the hatches and sandbagged the islands against a storm surge predicted to reach 6 to 11 feet. Then they'd boarded up the windows and evacuated both islands.

When Superintendent David Luchsinger and his team arrived on Tuesday morning, October 30, to assess the storm's damage, 75 percent of Liberty Island was under water. The only thing not covered was Liberty and her pedestal.

All of Ellis Island was under water—in some areas as much as eight feet.

"It was total destruction: windows blown out, doors blown out. The walkways were ripped up, all the basements were completely flooded. One dock was completely decimated, and the other one was pretty well destroyed," says Luchsinger.

"But while it was a very sad, sad day for us, we quickly realized it was also an opportunity to make this a more sustainable park. We began that day formulating our plans."

Cleanup started the next day and took about two months—the team working at first out of the back of a U-Haul with a couple of space heaters inside. Some structures, like Luchsinger's superintendent's house, weren't rebuilt. "I have the dubious distinction of being the last resident of Liberty Island," he says.

Two Become One

Liberty and Ellis Islands—both sitting ducks in a harbor vulnerable to rising sea levels—are linked in modern melting pot mythology, but their origins are distinct.

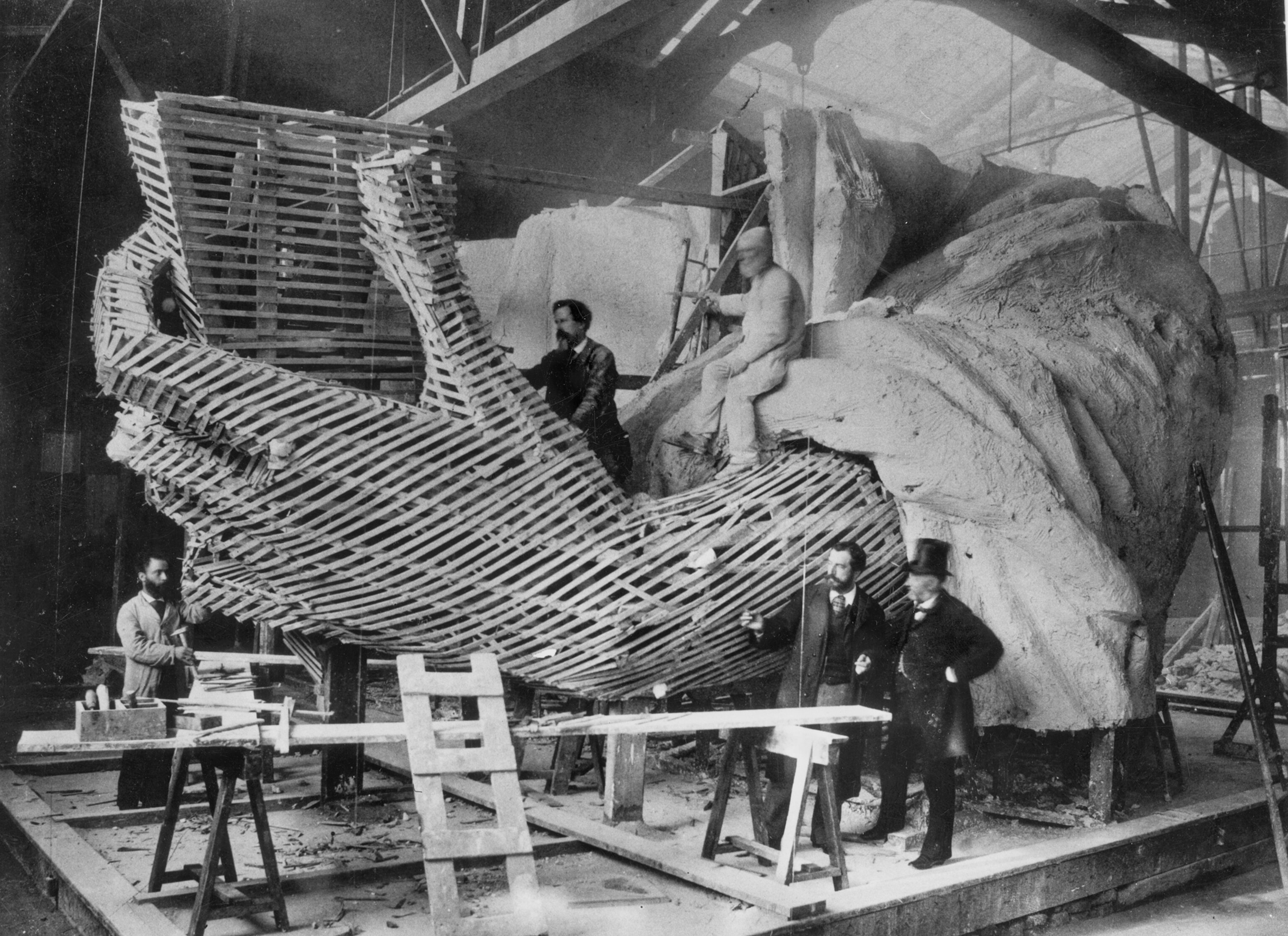

France proposed giving a statue to honor the United States in 1865, though the statue wasn't completed for 21 years. The gift celebrated the Revolutionary War alliance of the two countries and was France's way of supporting the ideals of freedom the new country espoused. Sculptor Auguste Bartholdi was also looking to create a sculpture to rival the Colossus of Rhodes. In 1871 he handpicked Lady Liberty's home, a 12-acre island in New York Harbor—all the better to see her.

Ellis Island's origins were less poetic. In the early 1800s, a fort was built on the island to defend the harbor and to keep the British from conscripting American soldiers. In the late 1880s, long after such dangers had passed, New Yorkers began complaining loudly about the risks posed by the 10,000 pounds of ammunition still housed at the fort, so it was converted into an office for processing immigrants entering the United States. Ellis Island's second life as a way station to the American dream began in 1892, six years after Liberty opened her doors.

Five years later Ellis's wooden edifice was destroyed by fire. The building rose again, built of hardier stuff—red brick trimmed in limestone and granite—and reopened in 1900.

On an average day, Ellis Island workers processed 8,000 to 10,000 immigrants. The record of 11,747 people was set on April 17, 1907. More than 12 million immigrants passed through over its two decades of operation.

In 1925, U.S. consulates took over the job of immigration. Ellis Island became by turns a deportation center, U.S. Public Health Service hospital, a Coast Guard facility, and an internment camp for Germans, Italians, and Japanese during World War II. By 1954, the U.S. government had run out of uses for Ellis Island and closed it. "People were coming into places other than New York, and the immigration laws were looser," says Luchsinger. It didn't reopen as a historic site until the 1990s. Only 17 ceiling tiles had been lost in the interim.

The Statue of Liberty was declared a national monument in 1924. In 1965, Ellis Island was folded into the Park Service site.

Ironlike Lady

On June 17, 1885, the Statue of Liberty arrived on American soil as 300 copper pieces packed in 214 crates aboard the French ship Isère, which nearly sank in rough seas while crossing the Atlantic. Liberty remained as unassembled parts for nearly a year as her grand pedestal—the largest concrete pour in the U.S. before the Hoover Dam—was completed.

Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel, creator of the famed Eiffel Tower, built an internal steel framework for the statue, securing her from the inside.

Liberty's copper exterior oxidized within a few decades, turning the statue green. But green is good. The layer of oxidation protects against further corrosion, so her guardians don't scrape it off. The lighter color now visible on her belly and cheek are the result of a partial sandblasting from superstorm Sandy.

She's got other survival tricks up her voluminous sleeves. Only about the thickness of two stacked pennies, she can sway about four inches, give or take. She needs to bend to avoid breaking in the harbor winds.

Only one thing has daunted Liberty since she was dedicated on October 28, 1886: An ammunition blast in 1916 knocked off her torch arm, impaling it on one of the rays of her crown. The arm was repaired and bolted back in place. The torch viewing deck has been permanently closed ever since.

Guarding Liberty

Statue of Liberty National Monument's former Superintendent David Luchsinger has a disaster-filled resume. With the National Park Service for 36 years, he volunteered to work Park Service lands in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

He was in New York for Sandy. Ditto for Hurricane Irene. He spent 1991's Hurricane Gloria and the nor'easter that followed at NPS lands on Fire Island—after which he spent two weeks canoeing over flooded land to his office.

He was also in NYC for September 11. That night, he grabbed a NPS boat and two Park Service rangers and closed down New York Harbor at the Verrazano Bridge. The Coast Guard, who would normally do the job, he says "was occupied with everything else that was going on."

Those experiences worked in Liberty's and Ellis's favor.

"One of the first things I did here—in fact on my first day on the job at Liberty and Ellis—I was supposed to sign off on a project agreement that would have called for our historic Ellis Island museum collection to be moved. I refused to do it and said, 'Unfortunately, you've picked a guy from Louisiana, and you're asking me to put my invaluable collection in a 50-year floodplain and I'm not going to do that,' " he says.

The project would have moved the collection to a building that flooded up to two feet deep during Sandy. "We would have lost our collection."

Tomorrow's Monument

Other problems weren't as easy for Luchsinger to circumvent.

A year to the day before Sandy hit, Liberty was closed for safety renovations and upgrades and to install a handicapped elevator that would go all the way up to the observation deck. Liberty reopened on October 28, 2012. It was open for exactly one day.

None of those upgrades were damaged during Sandy, but the energy infrastructure of both islands—HVAC and other mechanical systems, all housed in basements—were destroyed. "We've made this a very sustainable park—something it wasn't beforehand, but we've learned from experience," says Luchsinger. For example, the electric system of Liberty was moved to the second floor of an old incinerator building, well above flood level, and it was operational in time to reopen the statue to the public on July 4, 2013.

Ellis Island followed on October 28, 2013. There's little in the way of exhibits or videos at this stage, even the computer room where visitors can look up family members who immigrated through Ellis Island is still shuttered. The current visitor experience on Ellis is remarkably similar to what an immigrant might have seen: the baggage room and, upstairs, the great hall where the huddled masses awaited their personal interviews. It won't reopen in full until May.

"The only reason we're open on Ellis is because during restoration, the restorers put back the old radiator system. We were never going to use it, because we had a modern air handler system, but that got washed out," notes Luchsinger. "The only reason we're open is the old steam heat radiators."

Future Tense?

Does Luchsinger worry about the future of Liberty and Ellis Islands because of their exposure to the sea? "Sandy is by far the worst catastrophe the park has ever faced. We'd be foolish not to expect that things are going to be worse, given sea-level rise.

"Are we going to be ready for any eventuality? Absolutely not," he adds. "Anyone who thinks that we can prepare for everything that Mother Nature will throw our way is wrong. But I think we're very well prepared."

So is it Lady Liberty versus Mother Nature, then?

"Yeah, well, Lady Liberty, I don't think she competes with Mother Nature. She's built to move, to sway in the breeze. So if Mother Nature decides to blow a breeze our way, I think it's us against Mother Nature. Lady Liberty knows how to live with Mother Nature better than we do. Maybe we need to start rolling with the punches as well."

—Johnna Rizzo

Photograph courtesy US Library of Congress, National Geographic

Will Climate Change Swamp the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island?

Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty are in climate change's way.

Published December 26, 2013