Behind the Headlines: Venezuela's Crisis

Oil has long been the country's great stabilizer—and destabilizer.

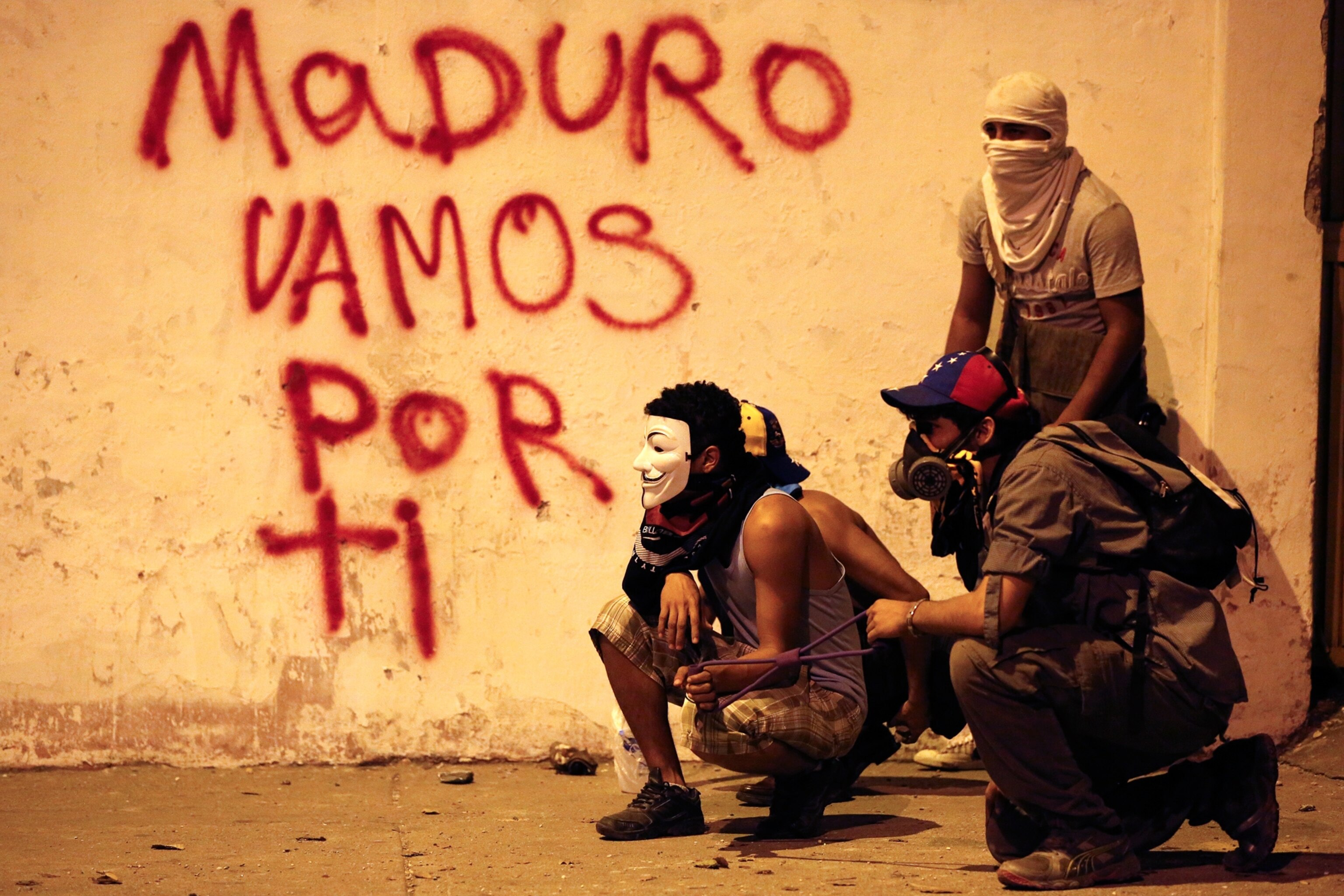

Venezuela's economy is unraveling—and so is the confidence of the country's hard-hit population. Soaring crime, high inflation, and a plummeting living standard have sparked weeks of protest in Caracas and other cities.

President Nicolas Maduro claims the opposition is trying to stage a U.S.-sponsored coup, but his accusations and free-speech curbs further fuel the popular anger.

Even with the opposition's Harvard-educated leader in prison, the protests are gaining supporters and the violence in the streets shows little sign of abating.

This is hardly the first time Venezuela has erupted. But unlike the current unrest in countries like Syria or Ukraine, which pits ethnic, religious, or regional groups against one another, "What we're seeing in Venezuela is different," says Arturo Valenzuela, a professor of government at Georgetown University and assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere Affairs. "It is a clash of economic sectors."

The essential question behind that clash is how to distribute the wealth of what many say is both Venezuela's greatest asset and greatest destabilizer—oil.

"The single most important geographic fact for Venezuela is that it has one of the greatest reserves of hydrocarbon in the world," says Valenzuela. "But that is also its curse."

A Nation Built on Oil

Many think that the discovery of oil is new for Venezuela, a product of this past century. But its history stretches back hundreds of years. Miguel Tinker Salas, professor of Latin American history at Pomona College, says the country's oil wealth boomed with the discovery of vast reserves in 1914 and again in 1922 with the eruption of the Barroso II gusher near Lake Maracaibo, but it had also been encountered by the Spanish at the time of the conquistadors.

"Oil was so plentiful it bubbled to the surface. They sent a barrel to the crown [in 1539] as a cure for gout," says Tinker Solas, speaking from Caracas this week. "It was used to caulk boats, for roofing, to light fires. But because there was no industrial revolution yet, it had no wider use."

That all changed, he says, with the invention of the internal combustion engine and the decision of the British Navy to convert their ships from coal to oil in the early 1900s. During this time, agriculture in Venezuela was largely regional, not able to sustain a national economy, he says. There was coffee production in the western Andean states, cattle culture in the llanos (plains), and cacao cultivation in the central plains. (See pictures of Venezuela.)

In his book, The Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture and Society in Venezuela, Tinker Salas writes that, "with its unpredictable weather patterns, fragmented topography, impenetrable rainforest and implacable insects, Venezuela proved incapable of sustaining large complex and hierarchical structured Indigenous societies similar to those found in Mexico, Central America or the Andes.

A fractured geography not only accentuated physical boundaries but also cultural frontiers between groups..." As oil developed, the people of its countryside—with its malaria and other tropical diseases and dismally low life expectancy of 37 years—moved to the oil fields and rapidly developing urban centers of the country.

Weak Agriculture

By 1935 Venezuela was a net importer of food. With oil so lucrative, economic sectors like agriculture weren't developed to their full potential.

Caracas—a city developed by the Spaniards away from the coast to protect it from marauding pirates and unrest—found itself crowded with shantytowns and newcomers, he says.

Today, Venezuela is of the most urbanized of all the Latin American countries. "As a result of what's known as a resource curse, there was a geographical displacement of the vast majority of the populace into the cities," says George Ciccariello-Maher, assistant professor of history and politics at Drexel University.

Nationalization of Oil Industry

In 1978, American companies found themselves kicked out as oil became nationalized. But the oil boom of the 1960s and '70s saw a bust in the '80s as oil prices fell. Riots reached a peak in 1989, 25 years ago this week, when the country's leadership tried to implement austerity measures.

The poor—distraught over rising gasoline and bus ticket prices—tried to take over the city. "This had a profound, traumatizing effect on the whiter, wealthier classes," says Ciccariello-Maher. "Caracas became segregated and militarized, with gated neighborhoods. The geographic impact of that political movement was profound."

One military officer, Hugo Chávez, joined others in the security forces who didn't want to take further part in efforts to repress the protests. He rose to power in 1999, remaining president until his death last year. (See "Hugo Chávez Leaves Venezuela Rich in Oil, But Ailing.")

He drew inspiration from South America's most celebrated independence hero, Simón Bolívar, who played a leading role in Latin America's fight for independence from the Spanish empire. Chávez even dubbed his socialist, anti-American movement the "Bolivarian Revolution."

That revolution, however, appears to be on unsteady footing now, especially in the cities.

Opposing the Socialist Way

"The main cities of Venezuela are found in the arco costa-montaña (coast-mountain-arc)—the mountainous region of Venezuela (the Andes) and the Coastal Range—because they have the most fertile soil and healthiest climate of the country," says Tomás Straka, a historian at Andrés Bello Catholic University in Caracas.

These cities are where the petrodollars were invested and where most of the Venezuelan middle and upper classes live, and many are governed by leaders who oppose the socialist leadership in Caracas. (Also see "Venezuelan Refinery Under Scrutiny After Deadly Blaze.")

In Caracas itself, some of the neighborhood lines drawn after the 1989 protests remain in effect now. "The social geography of the city has an influence on the protests today," says Straka.

"In Caracas, the spatial division of the classes and its political consequences are particularly clear. By 2002-2003 [a time of protests and a coup attempt against Chávez] separations were already evident: The east, where the middle and higher classes live, was the scene of protests against Hugo Chávez, while in the west, where the working class is the majority, were the supporters of Chávez. Nowadays, although this division in general still remains, some areas of the west have started to protest as well." (Watch a video of the Chávez era.)

The recent upheaval first began with students protesting deteriorating security after an alleged campus rape attempt in the city of San Cristóbal, but protests have swelled to include older Venezuelans fed up with rising prices and scarce goods.

Protesters are also upset, says Straka, over a crackdown on independent media and angry over the behavior of colectivos (created by Chávez and supported by him), which are fashioned as political organizations but act in some cases as paramilitary groups. Roaming the city on motorcycles, the colectivos appear to be behind several recent attacks, including one that led to the deaths of three demonstrators.

Neighborhoods that have seen some of the roughest protests, like Altamira, are in fact located in some of the wealthier, more middle class areas, where the government's economic policies and its expropriation of factories and other antibusiness measures are most strongly denounced.

The poor have suffered in the downturn, too, but as a disenfranchised community it has been more supportive of government price controls and other subsidies.

At the heart of the debate, says Drexel's Ciccariello-Maher, are "two visions" of the country and how its oil wealth should be distributed and spent: Should it go to social programs for the county's poor, or should it target other needs, such as an end to socialist policies or better policing—which are just some of the demands of protesters?

With the Crisis, Violence

"You have a genuine economic crisis going on," says Georgetown's Valenzuela, worsened by a failure of leadership.

"Venezuela has become one of the most violent countries in Latin America. What we've been seeing, actually, is the collapse of the state. This was exacerbated after the death of Chávez, who was a charismatic leader with magical appeal among his followers. (See "Pictures: Hugo Chávez's Venezuela.")

"His successors simply can't take on the mantle of Hugo Chávez."