After Washington Mudslide, Questions About Building in Nature's Danger Zones

Property rights issues and development are often at odds with safety.

On Tuesday, when President Obama tours the grim scene at the mudslide in Oso, Washington, where at least 39 people were swept to their death, he won't be able to do much more than comfort families of the victims and sign the disaster declaration that starts federal aid flowing to the tiny, shell-shocked community.

Preventing people from living in harm's way is a more complicated question, one not solved by a stroke of a presidential pen. The authority to restrict development in areas prone to risk lies with local and state zoning boards and building departments. But prohibitions on construction usually run headlong into property rights issues.

"There's your conundrum," says Lynn Highland, who heads the National Landslide Information Center at the U.S. Geological Survey in Golden, Colorado. "Local governments are between a rock and a hard place. They have responsibility to protect public safety. And they have pressure to build." (Related: "As Scientists Examine Landslide, Questions About Logging's Potential Role.")

Property Rights vs. Regulation

The tension between public safety and property rights may be a universal truth, no matter what the disaster. But local response varies widely.

Hurricane Sandy, which battered the East Coast two years ago, prompted two different approaches. New Jersey Governor Chris Christie pushed to rebuild homes on the coast; New York Governor Andrew Cuomo encouraged coastal residents to consider moving inland.

In Louisiana, a new report shows that the population of coastal regions is declining. More residents are moving away from coastal areas, as the fragile marshlands that protect inland communities erode.

But 25 years after Hurricane Hugo damaged or destroyed nearly every structure on several barrier islands off Charleston, the islands are completely rebuilt and property values have nearly quadrupled. The storm, which hit in September 1989, was the worst to batter the South Carolina coastline since 1872.

Afterward, building codes were toughened, although some homeowners won concessions that enabled them to build houses as big as 5,000 square feet (465 square meters). In some cases, stronger building codes have reduced flood insurance premiums, even though the island remains vulnerable to storms.

"It is impossible to be in a risk-free area," says David Breemer, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation, a Sacramento-based organization that defends and promotes property rights cases in court. "The solution is not necessarily to regulate out risk. It's to make property owners bear the risk as much as possible."

Landslides Are Different

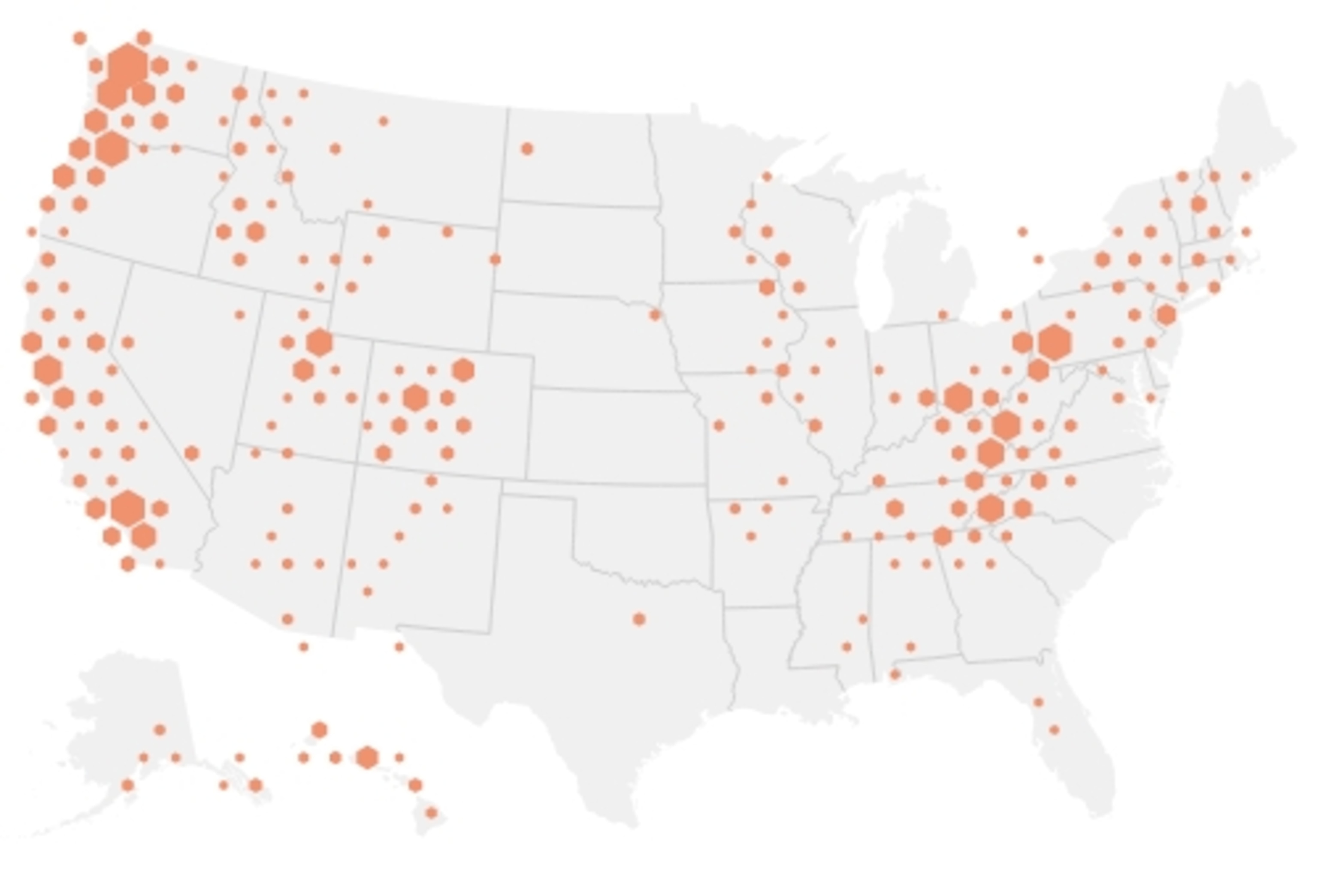

Landslides are less predictable than weather events like hurricanes. They occur primarily in the Appalachian Mountains, the Rocky Mountain West, and along the Pacific Coast. Most happen in remote, unpopulated wilderness areas and often go unnoticed. Each year, landslides claim between 25 and 50 lives, Highland says. (See "Mudslides Explained: Behind the Washington State Disaster.")

The USGS last mapped a national survey of landslide areas by hand in 1982—an outdated method in today's era of digital mapping. When Congress asked for an updated map—a task that would cost an estimated $25 million-it only appropriated $3.5 million.

Instead, Highland says she recruited 11 states to post their own landslide inventories on the USGS website. One of the states is North Carolina, which experienced a landslide in the western part of the state that killed five people in 2004. Afterward, the North Carolina legislature approved a plan to map landslide risks in 19 western counties. Then, after concerns were raised about the impact of the mapping on property values, funding for the program was cut and all but one of the geologists laid off.

Highland says what happened in North Carolina may be an extreme example, but "there is always going to be tension between property rights and government regulations.

"More people are moving into areas with slopes and into areas that have ground failure. A lot of it occurs on government-owned land. But enough is happening on private property, too," she says.

Back to Oso

The catalyst for the Oso slide, Highland says, was an unprecedented amount of rain. When the hill finally gave way on March 22, the resulting slide was one of the largest to hit a developed community in recent history. Mud, soil, and rock debris left a tail 1,500 feet (457 meters) long, 4,400 feet (1,341 meters) wide, and 30 to 40 feet (9 to 12 meters) deep, flattening two dozen homes along Steelhead Drive. (Related: "Washington Mudslide's Speed Led to High Death Toll.")

Searchers were still digging through the debris on Monday in an effort to find four people who remain missing.

The hill—locally known as "Hazel Slide Hill"—had had three major slides dating back to 1949, while two creeks in the area were known as Slide Creek and Mud Flow Creek.

The Seattle Times cataloged a litany of warnings from geologists, hydrologists, and other scientists who studied the area over four decades, including a 1999 report commissioned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that warned of a "potential for a large catastrophic failure." The corps approved the federal permit to the Stillaguamish Tribe to build a log restraining barrier, called a crib, at the toe of the slope.

Cases like the Oso mudslide usually get sorted out in court, Highland explains.

"A lot of people build in these areas and assume insurance covers them," she says. "And then they look at their policy and see it's not covered. Then they look around at the beginning of the problem, when the building permits were issued. That's when people find redress."

The first court claim, for $3.5 million, was filed last Friday by Corrie Yackulic, a Seattle attorney, on behalf of Debbie Durnell, whose husband, Thomas, was killed in the slide. The Durnells bought the house in 2011 as a retirement home. They were unaware of the hill's history, Yackulic says.

The claim is the first step in what could be a lawsuit against Snohomish County and the Washington State Department of Natural Resources.

Correction An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported that the Army Corps of Engineers erected restraining barriers at the toe of the slope. The corps approved the federal permit for the Stillaguamish Tribe to build a log barrier, called a crib, at the toe of the slope.