Global "Selfie" to Be Beamed to Outer Space

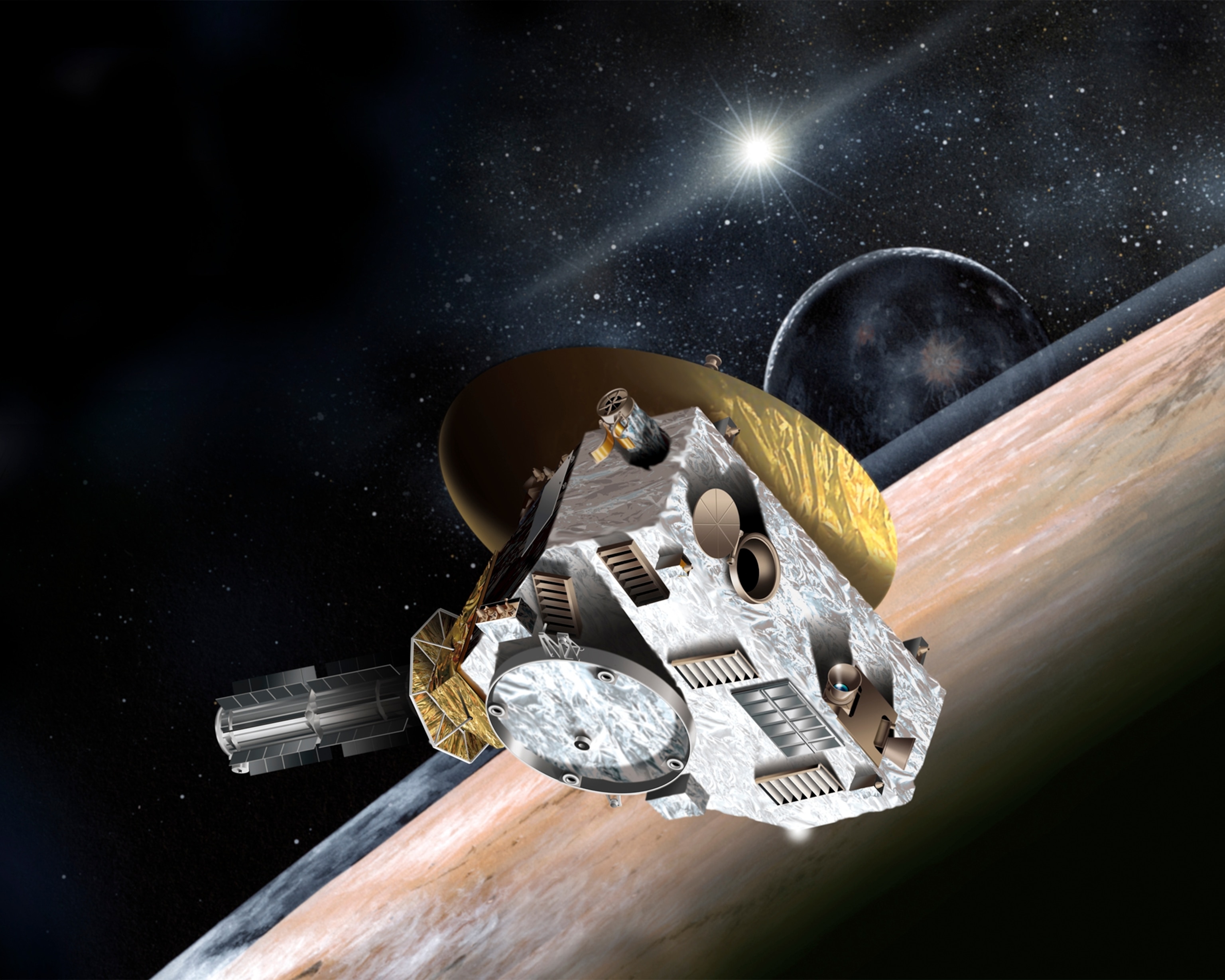

The crowd-sourced message will be uploaded to New Horizons spacecraft.

If you had the chance to send a message to aliens in outer space, what would you say? What would you tell them about life on Earth? How would you explain who we are?

These are not hypothetical questions.

This summer, you will get that chance to send a message to other worlds.

Jon Lomberg and Albert Yu-Min Lin, leaders of an initiative called New Horizons Message Initiative, announced Saturday at the Smithsonian Future Is Here Festival in Washington, D.C., that NASA has agreed to upload a digital crowd-sourced message to the New Horizons spacecraft.

The content of the message will be determined by whomever wants to participate in the planet-wide project. The message itself will be transmitted sometime after New Horizons does a flyby of Pluto in 2015 and sends back the scientific data that it collects.

If all goes according to plan, New Horizons will become the fifth man-made object to travel beyond the solar system—after Pioneers 10 and 11 and Voyagers 1 and 2. But it's the only one of the five not to launch with a message for any alien travelers it might encounter along the way. The Pioneer spacecrafts bore plaques on their sides, and the Voyagers each carried golden records (and the means to play them).

When New Horizons' journey was being planned—it launched in 2006—other missions had been scrapped and the budget was extremely tight, explains Alan Stern, the principal investigator in charge of New Horizons.

"I decided the message was the icing, not the cake, and we didn't have the bandwidth for it," he says. "Now I'm super in favor of this idea. It doesn't cost massive amounts because there's no hardware, just uplinking ones and zeroes."

Crowd-Sourced Content

Lomberg, who worked closely with Carl Sagan on the Voyager golden record in 1977, had an epiphany last year about sending the message digitally. An artist, he was creating a logo for the company Made in Space, which had proposed using 3-D printers in space to build tools that astronauts needed. "If they needed a wrench, you'd just send the file," says Lomberg. "It occurred to me that if you can make a wrench in space, why not a message in space?"

Lomberg approached Stern, who advised him that NASA would need evidence of public support. In September 2013, Lomberg launched a website with a petition to NASA. By February 2014, 10,000 people from over 140 countries had signed it. "The point," says Lomberg, "is to get people not as spectators, but as participants."

This message will be very different from the one Lomberg designed with Sagan almost 40 years ago. The golden record was created by an elite cadre of people over a breathless six weeks. The New Horizons message will be put together by as many people as choose to participate. "It was very presumptuous of Carl Sagan and the rest of us to speak for Earth," says Lomberg, "but at the time it was either do it that way or don't do it at all."

The 21st-century version will be a global self-portrait, pieced together by many willing hands. Lomberg calls it a selfie. Anyone on Earth will be able to upload potential content (images, sounds, software—the formats haven't been finalized). Then everyone will be able to vote on what to include. "Our team is going to provide the overall architecture of the message," says Lomberg, "but we'll try to keep ourselves open to what we will send."

Slow Download Speeds

Lomberg came up with the idea, but Lin, a National Geographic emerging explorer and expert on crowd-sourcing, is the one who will have to figure out how to wrangle a planet's worth of opinions into the roughly 100 MB of memory New Horizons will have available on its computer.

Luckily, Lin has some experience soliciting thoughts from a virtual crowd. He has harnessed what he calls the human computation network—Internet users poring over satellite maps—to home in on possible locations for Genghis Khan's tomb. (Lin worked with the National Geographic Society on that project; the Society will be involved in some capacity with this one as well.)

"As much as possible," says Lin, "we want to make this democratized." Anyone with an Internet connection can participate, but the project team will also reach out to groups without Internet access in an attempt to get "a true sampling of what represents life on Earth."

Although the project will officially launch August 25, the final file may not be sent for several years. The New Horizons computer won't have any room in its memory until the data from Pluto are transmitted back to Earth, which could take more than a year. "The spacecraft is so far away," says Lomberg, "that download times are like dial-up Internet."

And Pluto may not be the final mission target. Stern hopes that the spacecraft will have a shot at a flyby of another object in the Kuiper Belt of the solar system. If that happens, the message upload will be delayed. "I want to do this message project in a way that doesn't risk the scientific mission," says Stern.

Long Odds of Alien Contact

Delays don't worry Lomberg. "As long as the spacecraft is healthy and the radio is working," he says, "there's no particular rush to send it before everyone's happy."

According to Stern, the spacecraft could outlive Earth. "The spacecraft will be in the middle of nowhere," he says. "Nothing can happen to it." However, cosmic radiation may eventually corrupt the spacecraft's electronic memory. The New Horizons message won't last nearly as long as the metal missives attached to Pioneer and Voyager will.

But the odds that the messages will reach their intended extraterrestrial recipients are about the same for all five spacecraft: extremely low. Stern tallies up the obstacles to an alien encounter:

"One, are there aliens? Two, if there are, are they capable of spaceflight? Three, if they are capable, are they going to find something the size of a piano in space? Four, if they do find it, will they care enough to pick it up? Five, if they pick it up, are they going to take it apart? Six, will they know how to access the computer?"

But to Stern, it doesn't really matter if the answer to all those questions is no. "In my view," he says, "this is really a message to ourselves with the wonderful twist that it's possible—regardless of how unlikely—that it will be found."

So, think about it. What do you want to say about life on this pale blue orb? What do you think we, as a species, should say—to ourselves and to our unknown neighbors?

"This is a time to be reflective," says Stern, "and have a little fun."

Follow Rachel Hartigan Shea on Twitter.