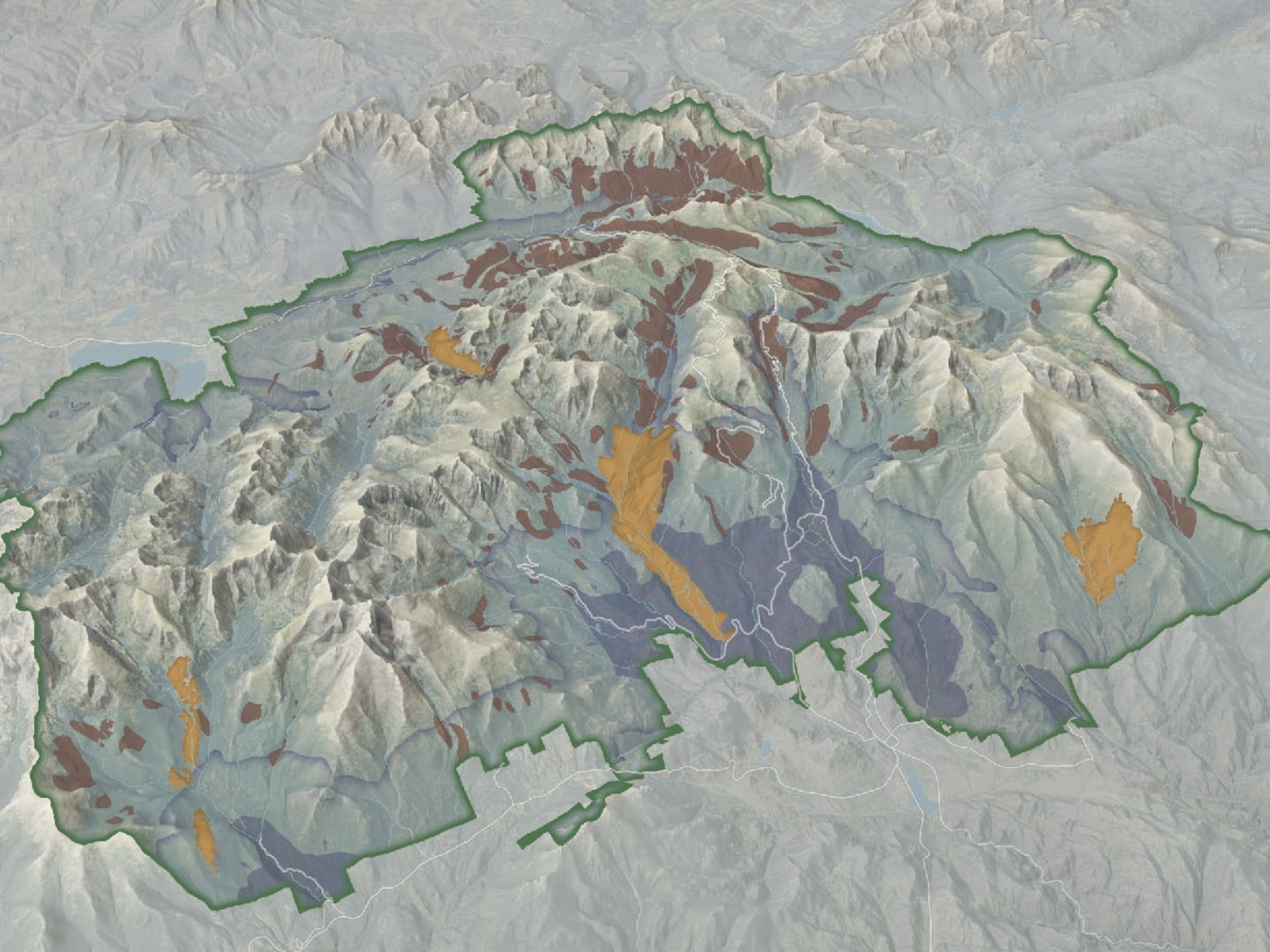

Study Finds "Extreme" Climate Change in National Parks

Global warming threatens visitor experience and national treasures, scientists say.

Many national parks in the United States have already experienced "extreme" climate change over the past few decades, and the trend is likely to accelerate unless bold steps are taken, government scientists warn in a new study.

Those changes are likely to disrupt visitor experiences and damage natural and cultural resources.

"This report shows that climate change continues to be the most far-reaching and consequential challenge ever faced by our national parks," National Park Service Director Jonathan B. Jarvis said in a statement.

For the study, published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS One Wednesday, National Park Service scientists studied weather records from 289 U.S. parks for the years 1901 to 2012. They then compared the historical trends for that period with the trends over the past few decades.

The results show that "many of our parks have been changing in extreme and dramatic ways over the past 10 to 30 years," says study lead author Bill Monahan, a parks service scientist based in Fort Collins, Colorado.

The study authors wrote that "parks are overwhelmingly at the extreme warm end of historical temperature distributions" for several key variables, including annual mean temperature, minimum temperature of the coldest month, and mean temperature of the warmest quarter.

Eighty-one percent of the parks studied have seen such extreme heat in the past few decades, Monahan says. Notable examples include Grand Canyon in Arizona, Sequoia and King's Canyon in California, Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, and Appomattox Court House National Historical Park in Virginia.

Precipitation has been more variable across the parks over the past 112 years, although Monahan notes that 27 percent of the parks have seen extreme drought in recent decades. Mojave National Preserve in California and Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Nevada and Arizona have been unusually dry, while Cape Lookout National Seashore in North Carolina and Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area in New Jersey and Pennsylvania have been extremely wet.

Looking into the near future, the study suggests that "everything in the parks is affected by climate change, from glaciers melting at Glacier National Park to the lack of tree propagation at Joshua Tree National Park," says Stephanie Kodish, the clean air program director for the nonprofit National Parks Conservation Association. (See "10 Most Visited National Parks.")

Parks as Climate Laboratories?

The new study "saw a strong correspondence to the results that came out in [the Obama administration's May 2014] National Climate Assessment," says Monahan. But the new study provides more granular detail of local conditions within parks than that broader report.

"What's important for us is that parks experience climate change at the local level, so managers need climate data at that scale so they can factor it into their plans," he says.

Kodish says the parks data is especially useful because it is based on a "long, unbroken chain of information." That's because parks officials have kept detailed records on what's happening on their lands for more than a century.

Kodish calls the study "another piece of information that tells the story of what things look like and how important it is to manage and mitigate climate change."

Visitor Impacts?

The study warns that future visitors to national parks may have to contend with hotter, drier weather (or in some cases wetter weather); loss of scenic glaciers; disruptions to vegetation and wildlife; and rising sea level.

For example, the report warns that rising seas and more severe storms threaten the cultural and archaeological sites in Jamestown, Virginia. At Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park in Maryland, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia, increased flooding may damage historic bridges, locks, and monuments.

In the Grand Canyon, drier conditions may result in loss of natural springs that sustain wildlife.

"With an eye on the approaching National Park Service centennial in 2016, the report highlights the need to provide up-to-date scientific information to park and neighboring land managers, and for sufficient climate science to be disseminated to the general public so that parks are positioned to protect their resources for future generations," the agency said in a statement.

"The longer the delay in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions that lead to climate impacts, the more exacerbated the effects will be on national parks," says Kodish.