1 of 11

Climate change could threaten half of North American birds by the end of the century, according to a new study from the National Audubon Society.

“Half of the birds of North America are at risk of extinction,” says Gary Langham, Audubon’s chief scientist. That estimate is based on the 314 bird species, out of 588 studied, that could lose most of the area they currently occupy, because of a warming planet.

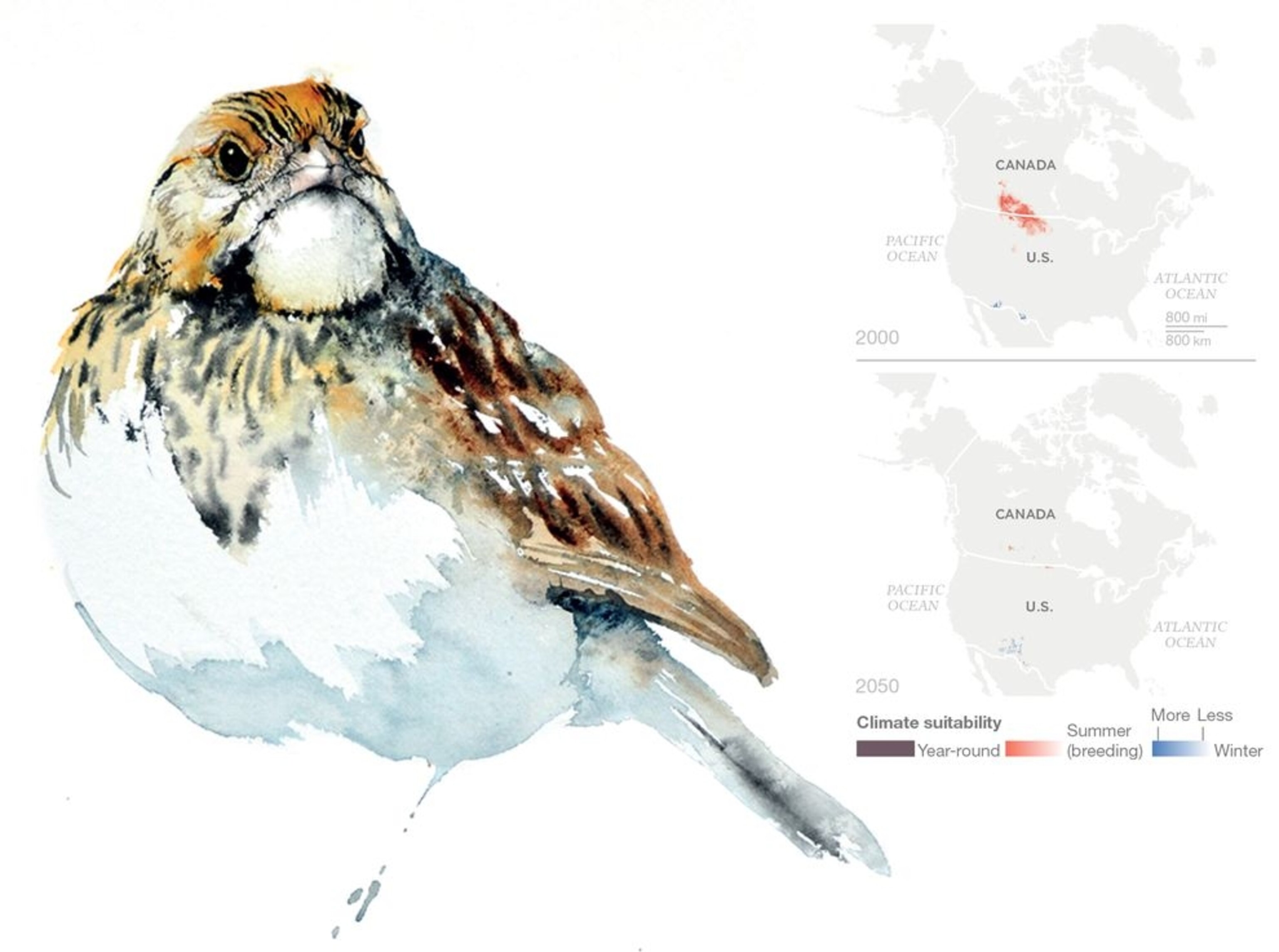

Nearly 200 of these threatened species may find hospitable conditions elsewhere, but for 126 species there will be nowhere else to go, Audubon estimates in a report released Monday night. Shifts in climate could affect the range of grasslands, forests, and other bird habitats.

Scientists have known for some time that species of all kinds will have to move—and in some cases are already moving—to adapt to the changes wrought by a warming planet. “What’s important about this particular study,” says Joshua Lawler, an ecologist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the study, “is that it’s built with a really solid data set.”

Audubon did not examine all of the more than 800 bird species that can be found in North America, but focused on those for which reliable data were available.

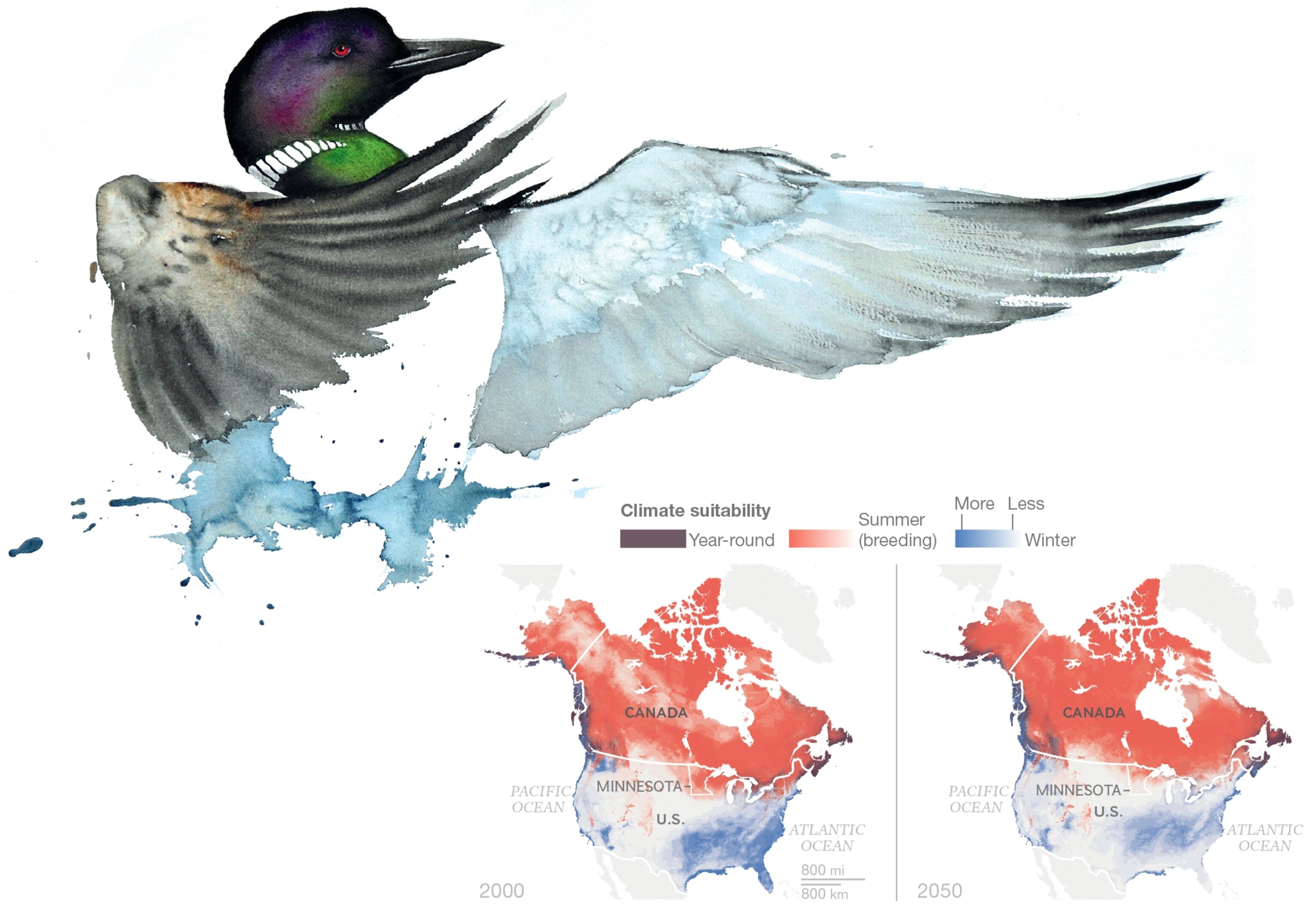

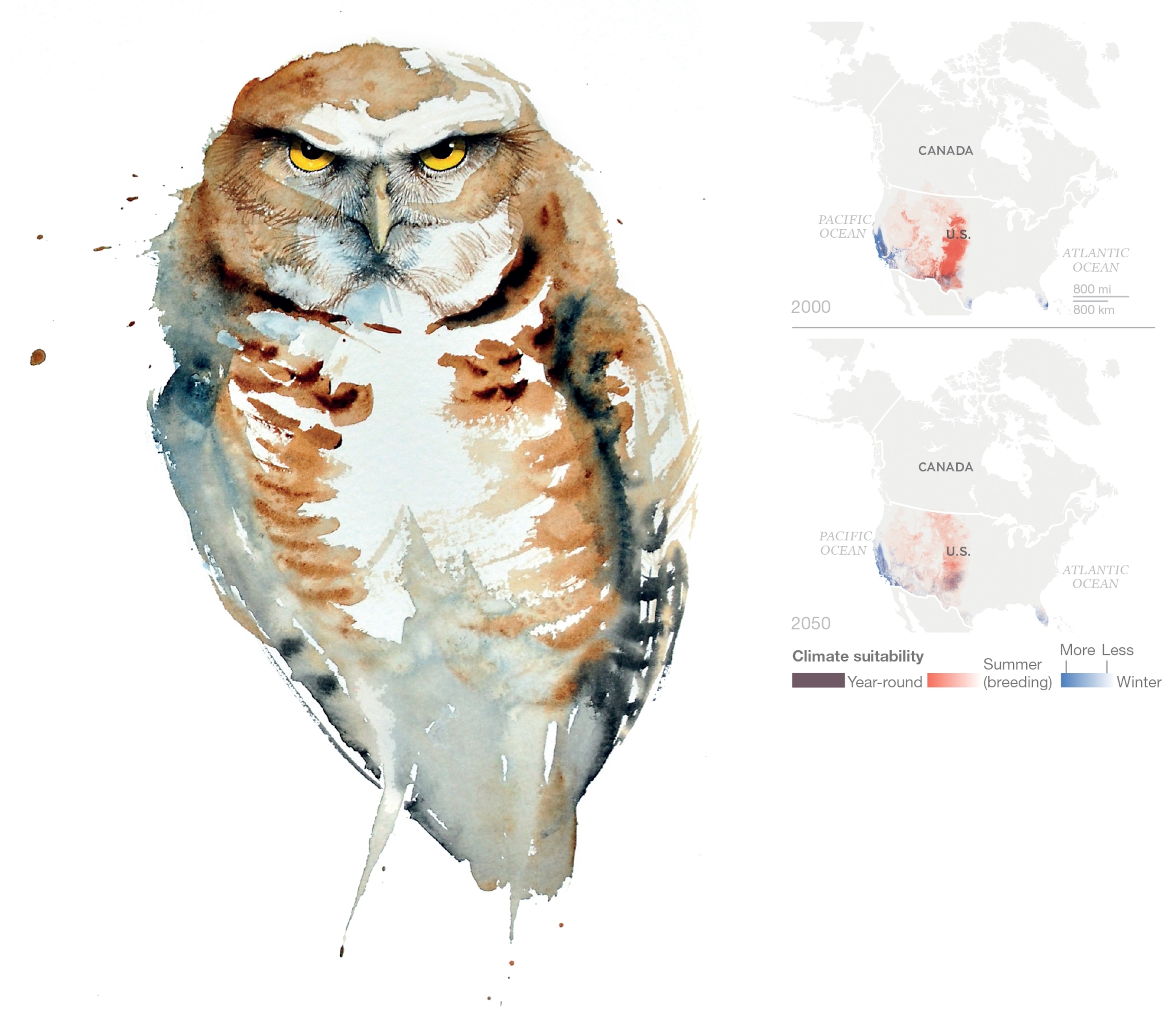

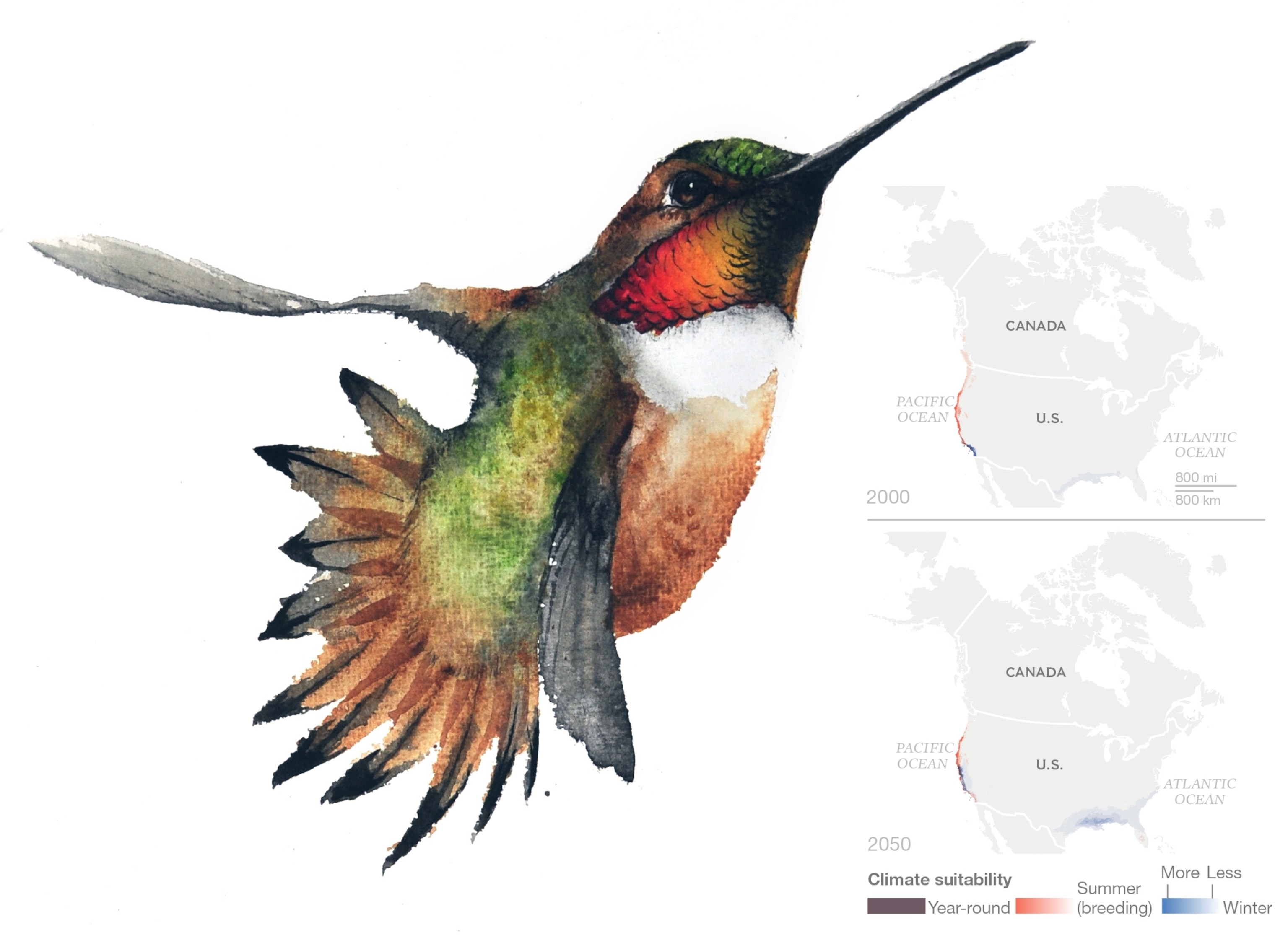

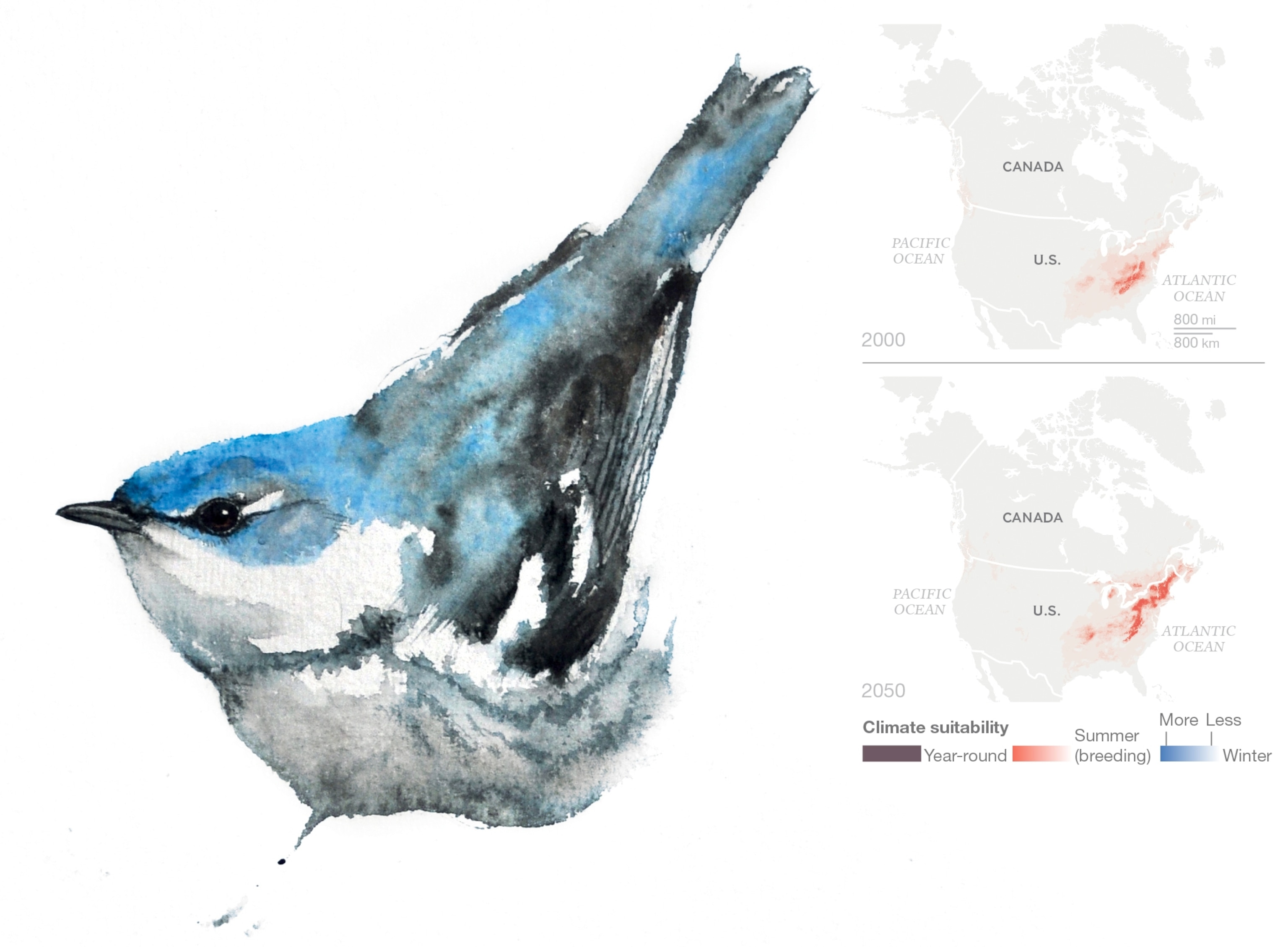

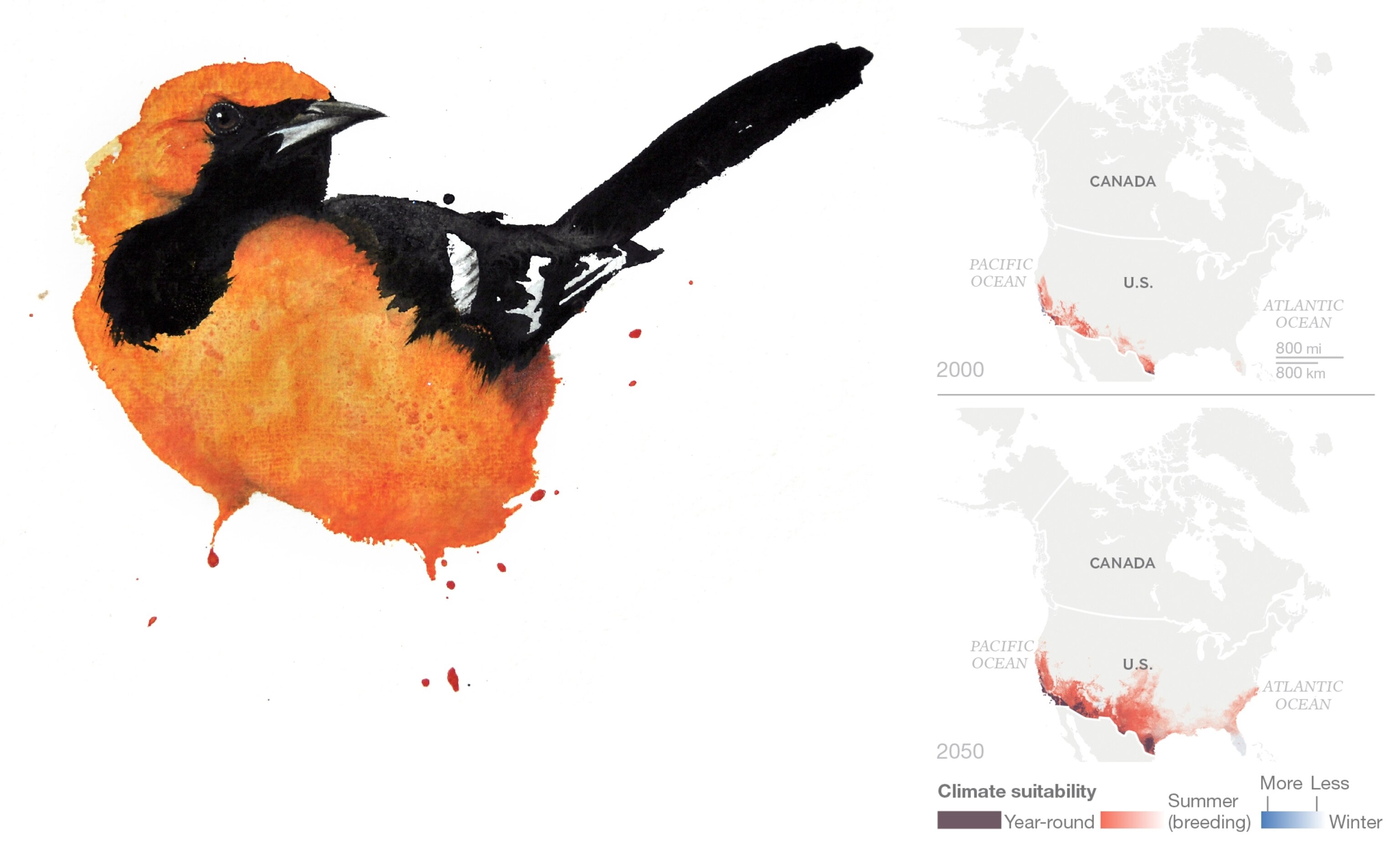

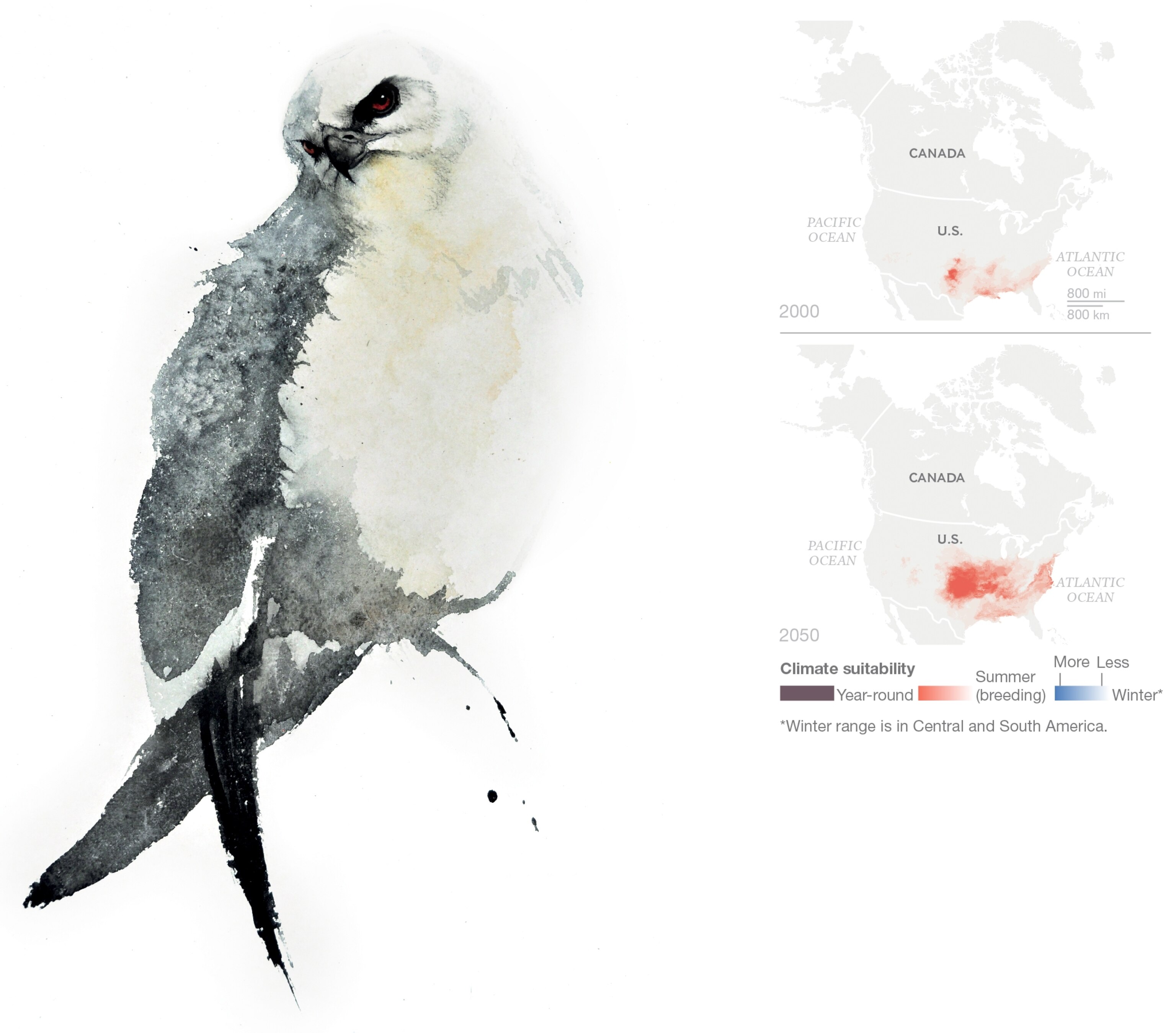

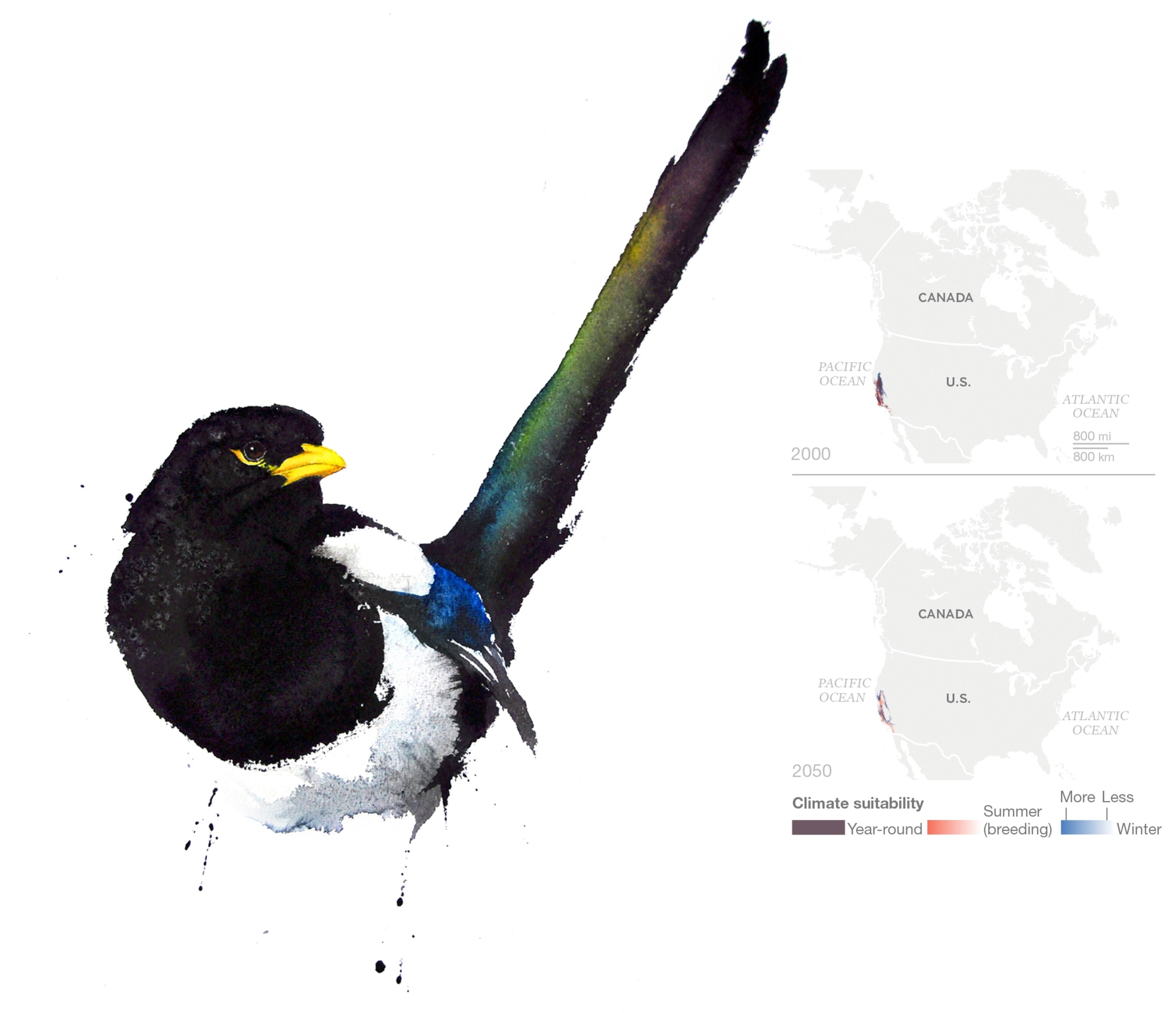

The new study combines 30 years of citizen science—bird observations across North America in winter and breeding seasons—with projections of future climate to see where suitable ranges might shift for different species. The citizen science comes from Audubon’s own Christmas Bird Count and the U.S. Geological Survey’s North American Breeding Bird Survey; the climate models are from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The results are “deeply worrying,” says Stuart Butchart, head of science for BirdLife International. “They add to a body of studies elsewhere in the world showing that climate change is going to have major impacts. Species are going to have to shift their ranges, and many overall are going to suffer range contraction.”

“Better Than Flying Blind”

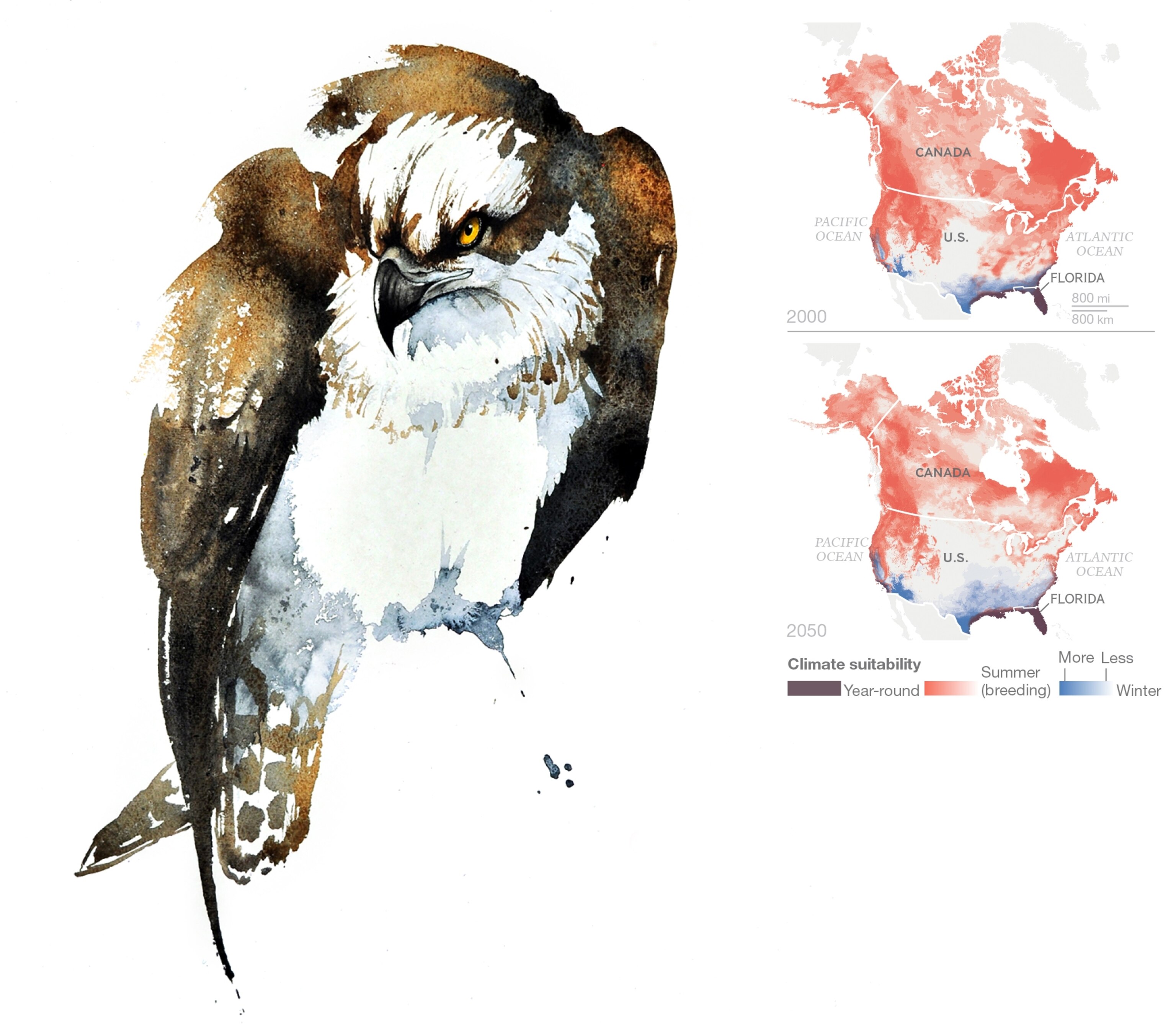

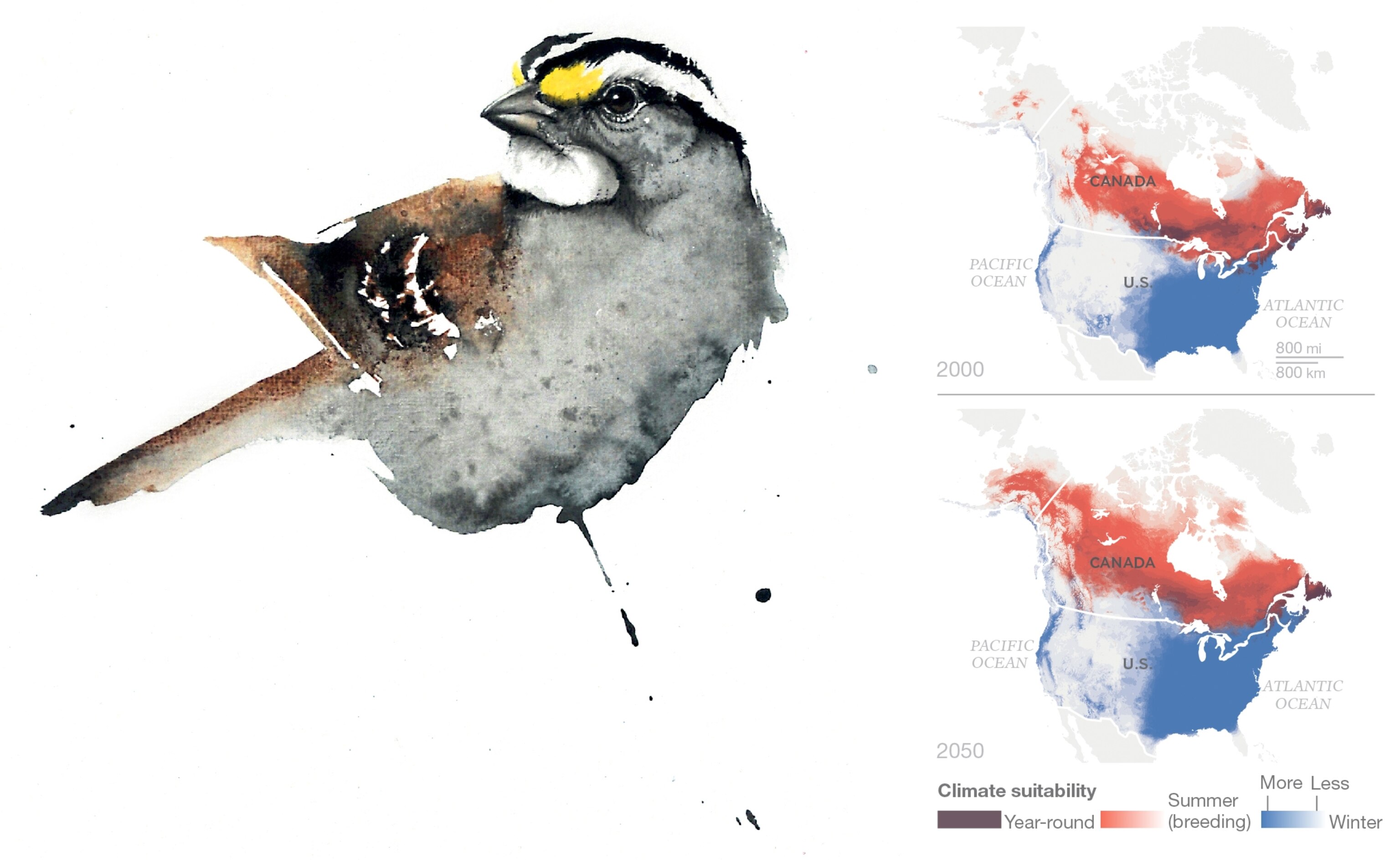

The study generated maps of climate suitability for 588 species in the continental United States and Canada. Suitability was determined by the conditions under which the birds had been observed in the past and where those conditions might appear under future greenhouse gas emission scenarios.

Surprisingly, few patterns emerged in terms of revealing which kinds of birds would be affected most. “This is really a species-by-species thing,” according to Langham, who says he thought before the study that bird species sharing a niche that depends on climate—birds that live in grasslands, for instance—would respond similarly to climate change. Instead, he says, “it’s pretty idiosyncratic.”

Not only are there few patterns, there are few indications of exactly which climate factors will drive particular species off their ranges, such as higher temperatures or changes in precipitation.

“To have a really good idea of whether a species is going to need to move or not,” says Lawler, “one needs to know all those bits and pieces: how their physiology responds to increasing temperatures, how changes in temperature or moisture might affect their food resources, how their competitive relationships might change as climate changes.”

“It’s hard,” he adds, “because the data don’t exist, even for those species that are really well studied.”

Within those limitations, says Langham, “we were able to use a simple set of variables to capture a lot of ecological complexity without having to make assumptions about which one is most important.”

“It’s not the answer,” he adds, “but it’s much better than flying blind.”

What is clear, he says, is that although some regions, such as the northern Canadian provinces, may gain species, “loss is more certain than gain.” An area’s climate may become more suitable for a specific species—with the right temperature, precipitation, and seasonal fluctuations—but the rest of the habitat may not.

“It doesn’t really matter what your climatic niche shifts to if you don’t have things to eat,” says Langham, offering a California native, the oak-loving yellow-billed magpie, as an example. “Even if oaks could grow north of where you are now, they’re going to take 40 years to mature.”

Expanding Endangered Lists

As part of the study, the Audubon Society created a climate-based list of endangered species, dividing the 588 bird species studied into three groups: climate endangered (projected to lose more than half its current range by 2050), climate threatened (projected to lose more than half by 2080), and climate stable.

There’s little overlap between Audubon’s climate-endangered list and other endangered lists, and for good reason: Few of the birds at risk from future climate change are currently endangered. And the society’s list addresses threats only from climate change-caused range reduction, not from current threats such as habitat loss or environmental pollutants.

Currently, 1,373 bird species worldwide—13 percent of known species—are on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, a widely used measure of birds’ status that does not currently account for risk from climate change. The Audubon study “gives us a longer-term view,” says Butchart, who works closely on the Red List. “It’s telling us that a whole additional suite of species will become highly threatened that aren’t the ones we’re worrying about now.”

“A Field Guide to the Future”

Despite the grim prognostications, Langham argues that there’s reason to be hopeful. Mapping each species’ climatic range and assigning it a threat level “helps us conserve birds,” he says.

The study-generated range maps are detailed enough—defining areas as small as 38.6 square miles—to give conservationists and natural resource managers a general idea about where to concentrate their efforts. Langham hopes the maps will serve as “a field guide to the future.”

Already, says Lawler, “these kinds of studies are changing the way that conservation at a large scale is being done.”

“It’s not too late to do something,” insists Langham. “If you give birds half a chance, they respond.”

Follow Rachel Hartigan Shea on Twitter.

Art: Karl Mårtens. Source: National Audubon Society

Climate Change May Put Half of North American Birds at Risk of Extinction

An Audubon Society study finds that climate change will force 314 bird species out of their current ranges.

ByRachel Hartigan

Published September 8, 2014