Early Spread of AIDS Traced to Congo's Expanding Transportation Network

In the 1960s AIDS spread rapidly across the Congo, riding a wave of social change as the region developed and its transportation network expanded.

As the Ebola epidemic spreads, new information has emerged on the origins of a far more deadly killer. A new family history of the HIV virus that causes AIDS, reported Thursday, is troubling but instructive: Modernization in mid-20th-century Africa, especially in the city Kinshasa, played a profound role in shaping that global epidemic.

Ebola and HIV are spread in different ways—Ebola via direct contact and HIV mainly through sexual contact—and could take different paths as epidemics. But the new study, which illuminates the origins of the AIDS crisis, highlights the importance of understanding the social forces that drive epidemics as well as the mechanics of viral transmission.

"How the [HIV] virus first got from other species into humans has been studied in great detail," said Oliver Pybus, an evolutionary biologist and infectious disease specialist at the University of Oxford. "The question is, Why did one strain become a pandemic, while others stayed local?"

In a study published Thursday in Science, Pybus and colleagues investigated that question by analyzing HIV genomes gathered over the past 30 years from 814 people in central Africa. They compared these full sets of DNA and used them to reconstruct a tree of viral evolution, extrapolating backward into HIV's murky pre-epidemic history.

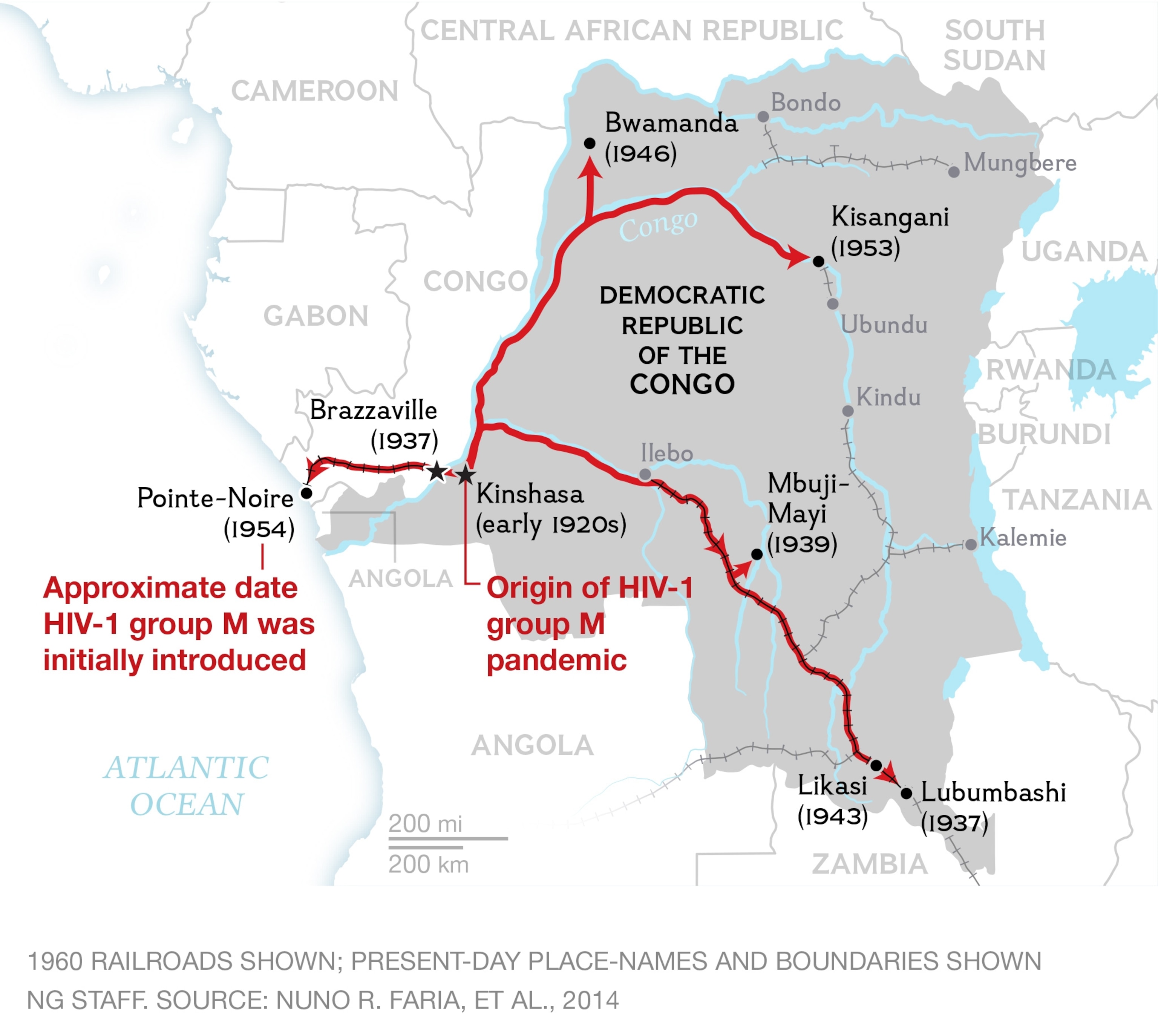

The city of Kinshasa, in what was then Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, played an important role as ground zero for the virus that would go pandemic, the researchers found.

Scientists already knew that HIV viruses had crossed into humans early in the 20th century, probably because central African hunters ate infected chimpanzees and other nonhuman primates. This happened not once but many times, putting into circulation in the local human population a host of different HIV viruses, including both the HIV-1 and HIV-2 types.

HIV-1 contains the viral groups called M and O. Group M is now responsible for 90 percent of pandemic infections and is the virus people typically mean when talking about HIV. Group O and HIV-2 also cause infections but remain geographically concentrated in central and western Africa. Other strains are rare or have fizzled out altogether.

The group M strain, says Pybus, appears to have "put its foot on the accelerator"—though it might be most accurate to say that humankind pressed that accelerator down.

Because the researchers knew where their samples had been collected, they could estimate HIV's geographic and evolutionary trajectories, identifying a crucial mid-century moment of divergence, around 1960. Before then, groups O and M had spread at similar rates. After, group M exploded.

The number of infections soon tripled, and the virus's range expanded across the vast Congo Basin. Laying the groundwork, say the researchers, was the Congo's rapidly expanding colonial transportation system.

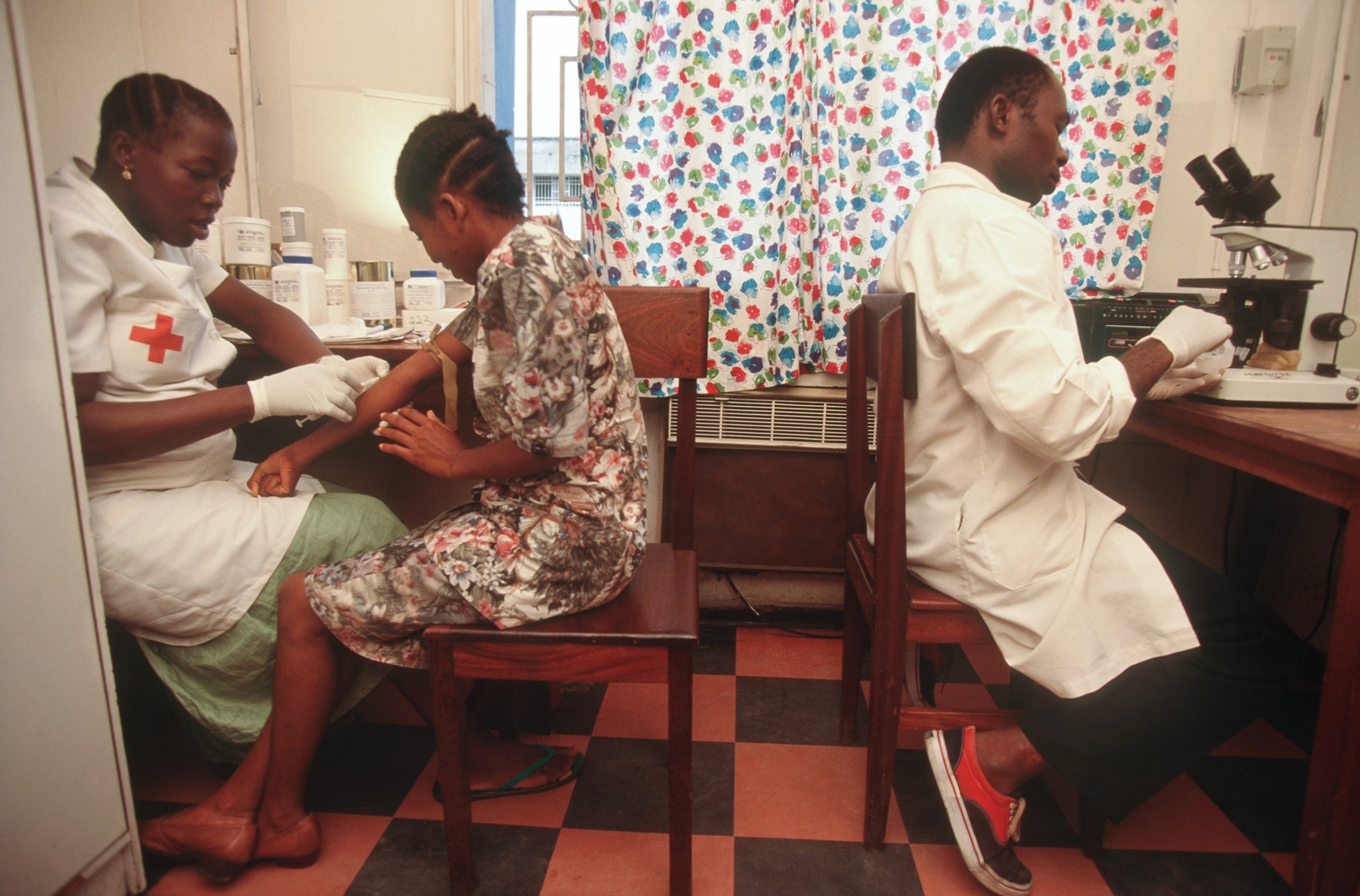

Riding the roads, waters, and railways between Congo's cities were millions of wage laborers. Most were men; sex work flourished. Group M viruses hitched rides, traveling from the commercial hub of Kinshasa to ports at the Congo River's mouth and cities in the region's far reaches.

The viruses' spread to other continents was only a matter of time. It's thought that they were carried to Haiti in the early 1960s by workers returning home.

Though some researchers have suggested that group M viruses were uniquely infectious, others have pointed to urbanization and unsterilized needles used at health clinics for sex workers. Viral adaptation can't be discounted, but the new analysis underscores the importance of social factors.

"If we want to stop isolated viral spillover events from becoming pandemics in the future, this is the sort of research we need," says disease ecologist Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, a conservation group focused on preventing disease outbreaks.

Expanding development—of agriculture, industry, transport, habitation, and trade—must be accompanied by better health care and disease surveillance, he says, and a deeper awareness of how human activities influence pathogen spread and evolution.

"The big question," Daszak says, "is what do we, as a species, do about this repeating pattern of development and disease emergence?"