Your Measles and Vaccination Questions Answered

What does it take for an outbreak to start? Do the unvaccinated endanger everyone else?

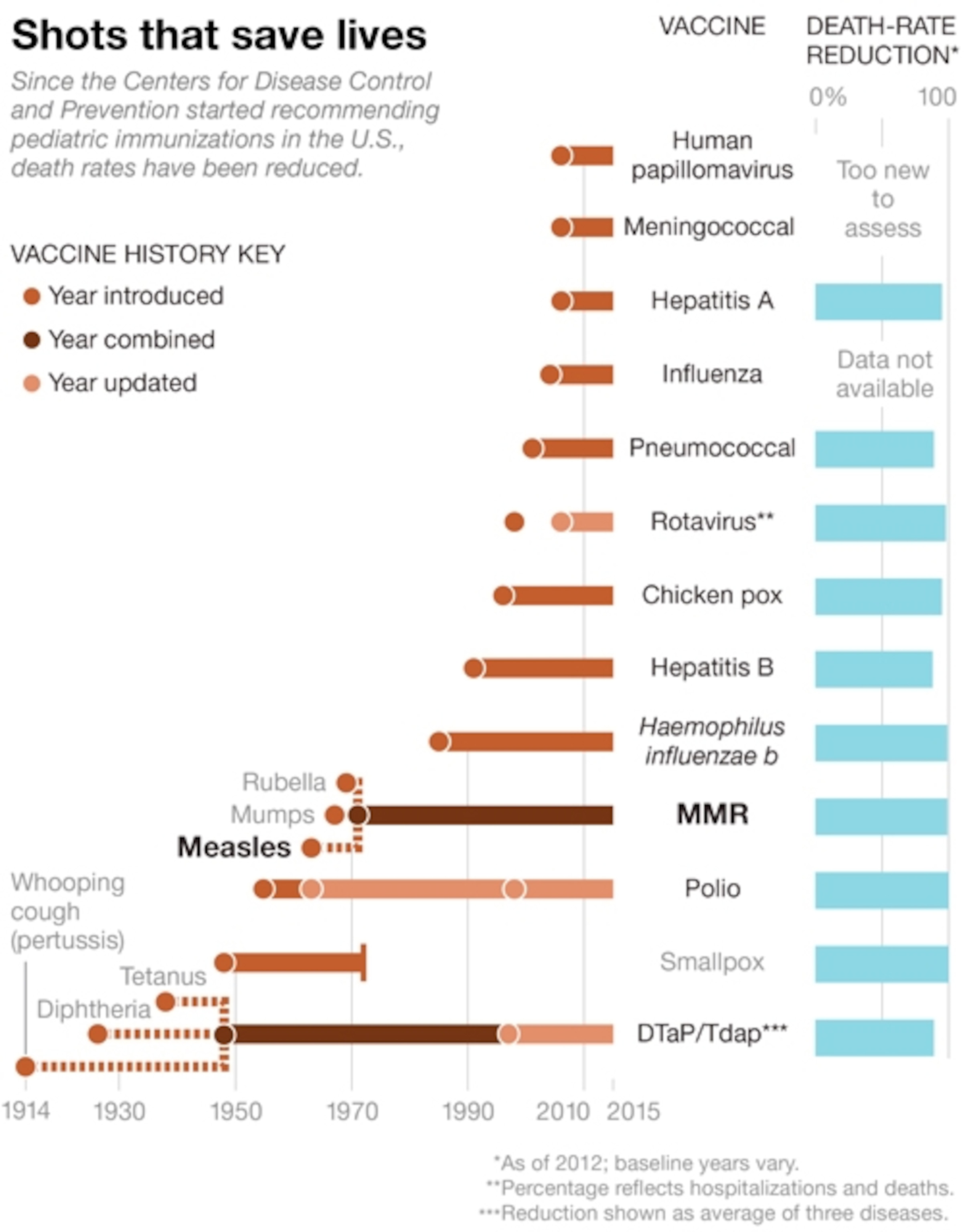

The debate over vaccines and the overwhelming media coverage that it's attracted in light of a measles outbreak tends to obscure a key fact about Americans: More than 90 percent are vaccinated against measles and other diseases.

Because of that level of protection, measles was essentially eliminated from the United States by 2000; the few cases diagnosed in the dozen years that followed were from people who carried the disease back from foreign countries. (Read "Why Do Many Reasonable People Doubt Science?" in National Geographic magazine.)

In the past few years, however, native infections have been creeping up again. The latest outbreak—which now includes more than a hundred infections—was likely sparked by someone who visited a Disney theme park in California in late December, though officials say they probably won't be able to identify the person who triggered it.

As the outbreak continues, here are key questions and answers about the disease and vaccinations, including why some people reject them:

Why can measles spread if so many people are protected against it?

The measles vaccine is 95 to 98 percent effective, but that small gap in effectiveness means that if a hundred vaccinated people are exposed to the disease, two to five of them could get sick. And the more people who are exposed, the more who will fall ill. A sick person at a popular attraction like Disneyland might expose thousands in a day.

Did people who refuse vaccination cause the current outbreak?

Most of the people who've gotten measles in the current outbreak were not vaccinated, according to Anne Schuchat, the assistant surgeon general and director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, part of the U.S .Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "This is not a problem with the measles vaccine not working. This is a problem of the measles vaccine not being used," she said at a news conference last week.

In recent decades, most American measles outbreaks have been started by people coming to the U.S. from other countries where the disease is more common, including Europe and the Philippines. Of the first 59 Californians who caught the measles in late December or January, the state has vaccine documentation on 34 of them, and 28 of those were not vaccinated, including 6 who were too young for the vaccination. Those 28 clearly contributed to the spread, officials said.

What does it take to start an outbreak?

Outbreaks generally require two things: an initial spark and enough unvaccinated people to feed the flames. Disneyland attracts visitors from all over the world, so someone who caught measles in another country could easily have carried it with them to the amusement park. There are relatively large numbers of unvaccinated children in California—where there have now been 92 recent infections—because of the state's liberal allowance to opt out of vaccinations on the basis of personal beliefs.

Other recent outbreaks have struck an Amish community in Ohio and Orthodox Jews in Brooklyn, New York, communities in which vaccination rates are lower because of religious objections. Rates are also below 90 percent among preschoolers in 12 states, including Colorado, Arkansas, and Michigan. In California, 91 percent of preschoolers have gotten their measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, according to the 2013 National Immunization Survey.

Why do some parents refuse to vaccinate their kids?

A clear scientific consensus confirms that vaccines are safe and highly effective.

But a small number of children can be harmed by any vaccination. In 1988, the federal government established a fund to cover vaccine injuries, which made payments to 2,542 families between 1988 and 2006. There's no way to identify ahead of time which few children will be harmed by vaccines. Many of those who avoid vaccines—including some families with children who have autism—worry that their child is particularly vulnerable and will suffer one of the rare cases of harm.

Researchers have repeatedly shown no connection between the MMR vaccine and any developmental disabilities like autism. But a portion of the public has been skeptical since a small, since—discredited study ran in the journal the Lancet in the late 1990s.

"We're really stuck now," says David Yassa, an infectious disease doctor at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, adding that he doesn't know how to reassure people other than with the facts. "The data is very clear in terms of the benefits and lack of risks of these vaccines."

People who choose not to vaccinate their children are taking a risk both for their own child and for the larger community, Yassa says. The more people who are vaccinated, the lower the likelihood that the disease will be passed to someone who is too young to be vaccinated or is otherwise vulnerable to the disease.

Are there people who shouldn't get the vaccine?

The MMR vaccine is generally recommended for children at 12-15 months and again before they start school. Children with a compromised immune system should not get the vaccine. A booster shot is considered safe for healthy adults who are unsure of their vaccination status.

Someone with a compromised immune system should not get the MMR vaccine because it includes live viruses, so theoretically it could make someone sick. For most other vaccines, like the polio vaccine and the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine known as DTaP, manufacturers use inactivated viruses that cannot transmit the disease.

Do the unvaccinated put the vaccinated at risk?

Religious and personal exemptions do not endanger other people, as long as roughly 95 percent of the population is vaccinated, creating what's called herd immunity. If the numbers of unvaccinated climb or there are pockets with lower protection, it can lead to outbreaks when the disease arrives from abroad.

Am I or my children at risk of contracting measles?

For those who are fully vaccinated, the risk of contracting measles is very low. First, you or your child would have to be exposed to the disease—and right now, only about a hundred people are infected in a country of 350 million. Then you'd have to be among the unlucky few who gets sick despite vaccination. Of those who get sick, fewer than a handful out of a thousand cases are extremely serious or life-threatening, according to the CDC.

Most Americans who are older than 51 were exposed to measles in childhood, when the virus was common in the United States, and so developed immunity. Beginning in 1963, children received one dose of the vaccine, which was about 93 percent protective. In the late 1980s, researchers discovered that a second dose bumped the protectiveness up to about 98 percent. Since then, American children have been given two doses, one at 12-15 months and the second no later than ages four to six.

The people who received only one dose, who are now mainly in their 30s and 40s, have slightly less protection than younger or older people. It's also possible that some people, particularly those vaccinated outside the United States, where the supply of vaccine might not have been kept continuously cold, didn't get an effective dose. Doctors may recommend vaccination before traveling overseas to a country where the disease is present.

How do you get the measles?

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases we know. In a roomful of unvaccinated people, 90 percent would get measles if one sick person entered. The virus passes through droplets in the air, usually from someone sneezing or coughing, and can blow through or hang in the air for a while. Tight spaces like elevators can be points of transmission, with germs lingering for hours.

What are the symptoms?

About eight to ten days after exposure, the person develops a fever, runny nose, and maybe muscle aches. Red eyes are also common. Most patients have a rash that starts on the face and moves downward and outward, with blotchy red spots that can blend together. The virus's contagious period usually lasts from about four days before the rash starts, and before a person could know he or she has the disease, until four days after.

Measles can be reliably diagnosed if the patient has most of those symptoms plus little whitish spots in the mouth, usually on the gums across from molar teeth. Because the disease has been rare since vaccination began more than 50 years ago, most doctors today have never seen a case of measles.

And then symptoms go away and people are okay?

In most people, the symptoms go away in one or two weeks. A small number of people can develop pneumonia or neurological conditions that can be life-threatening and long-lasting. The most vulnerable are children under a year old, who are too young to have been vaccinated; pregnant women; and people with compromised immune systems, such as older adults and those getting treated for cancer.