How Microsoft’s New Age Detection Software Works (and Doesn't)

We got some surprising results when we scanned pictures of our staff—and of our Neanderthal sculpture.

I look 51 years old in a recent photograph, according to Microsoft’s new computer program How-Old.net. I'm only 36.

My mother fared better. Microsoft thinks my 65-year-old mom is 20, based on another photo I uploaded, which isn’t actually that shocking. Mom still occasionally gets carded when buying wine at the grocery store.

Microsoft’s program has gone viral, with thousands of people uploading their own photos and sharing their horror, or pleasure, at how old the computer says they look, many with the hashtag #HowOldRobot.

Microsoft engineers knew the tool would have trouble getting everyone’s ages right but they wanted to put their software to the test. So on Thursday, the company unveiled How-Old.net, which employs an algorithm that guesses age and gender from photos. (In all the images I tested, the program successfully indicated the gender.)

The company's developers built the site with face recognition software created through a joint effort between Bing and Microsoft Research that's known as Project Oxford.

Here's how it works: The program extracts information from photographs and maps out a series of facial “landmarks,” such as the locations of the pupils and corners of the eyes, the boundaries of the lips, and the edges of the eyebrows. By running those points through algorithms, a computer can estimate age and gender based on data about how landmarks tend to change and shift with aging.

“An obvious example is that sagging tends to occur with age,” says Richard Russell, a psychology professor at Gettysburg College who studies faces and perceptions of aging but did not work on Microsoft’s project.

According to Microsoft, frontal and near-frontal faces have the best results, because the most number of facial landmarks are visible and aligned in a predictable way.

“How Old We Look Matters”

There are a number of reasons the computer’s age guesses can be pretty far off, says Russell. The photo might not be that clear, the lighting might confuse the computer, or the algorithm might misinterpret some landmarks or miss subtle clues that a person might detect, such as a stray wrinkle or a loss of color around the lips.

Other computer scientists have taken facial recognition science in a different direction, using software to estimate how a child might look as they age through their life.

Russell says such research is important because “how old we look matters.”

People treat each other differently based on how old they think they are, in work and love, he notes. And research shows that people who look older actually tend to die before those who look younger for their age.

“We don’t know why that is, but how old you look is a better predictor for mortality than how old you actually are,” says Russell.

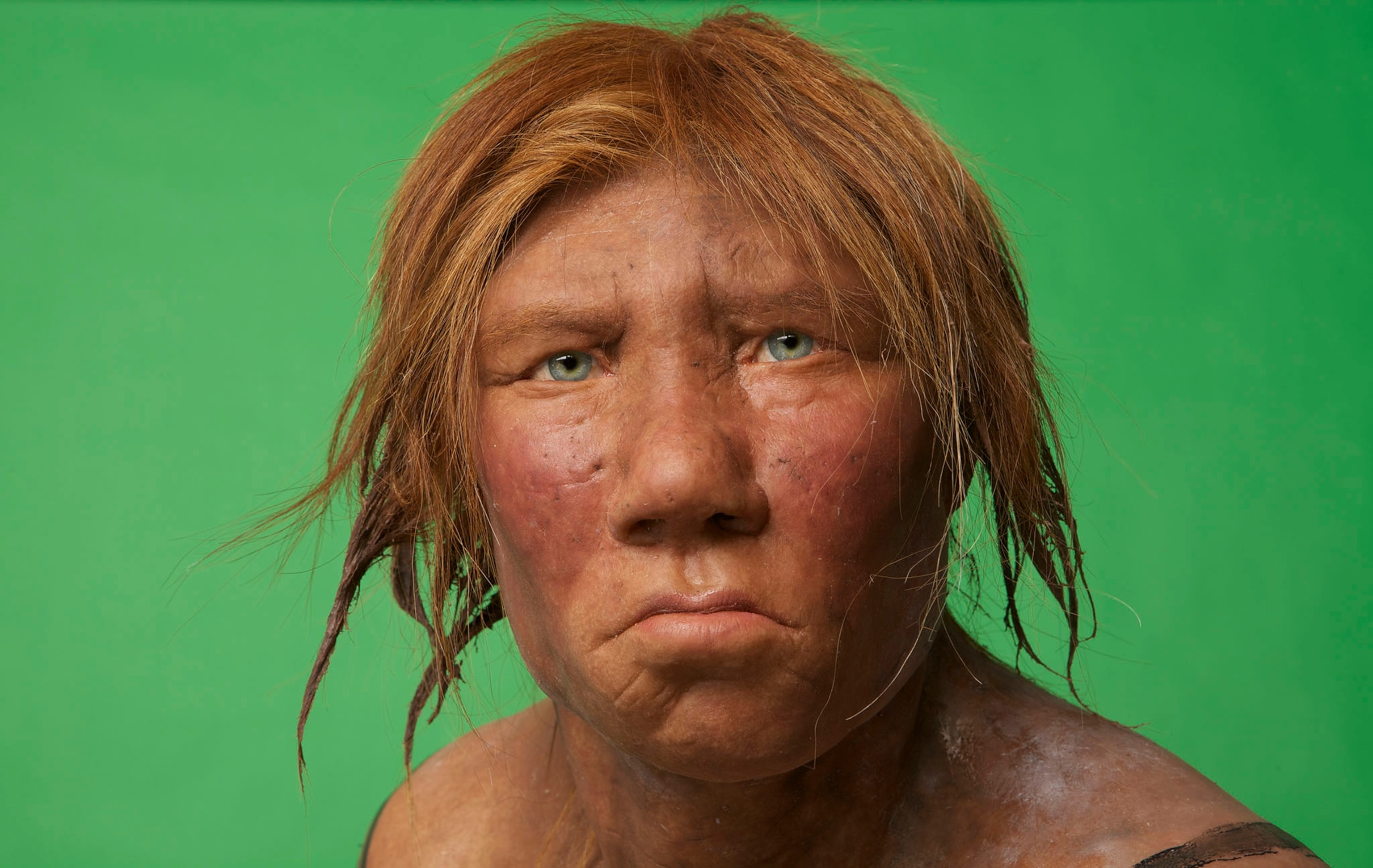

To really put the Microsoft computer to the test, I uploaded a photo of “Wilma,” the first model of a Neanderthal that's based in part on ancient DNA evidence. Constructed in 2008 from analysis of DNA from 43,000-year-old bones that had been cannibalized, Wilma now resides in National Geographic’s newsroom. And she's aged well: Microsoft’s software says she's 41.