With Flyby, Pluto Portrait Is Last New Face in Solar System

New Horizons makes its closest approach to the dwarf planet, focusing on data collection at the expense of phoning home until Tuesday night.

For the better part of a century, we’ve grown up learning about a solar system with nine planets. Revolving around a small, yellowish star, our dusty neighborhood was bounded for a long time by planet Pluto. Discovered in 1930, Pluto has remained a distant enigma for 85 years. Now, we’re getting our first look at the last planet.

At 7:49 a.m. EDT, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft flew within 8,000 miles of dwarf planet Pluto after a 9.5-year journey through the solar system. Though the spacecraft was quiet during the flyby—it won’t phone home again until later tonight—the scene inside mission control at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physical Laboratory was anything but silent, with hundreds of people erupting in cheers and waving flags at the moment of closest approach.

“Isn’t this a great day?” asked Annette Tombaugh, daughter of the man who discovered Pluto at the Lowell Observatory.

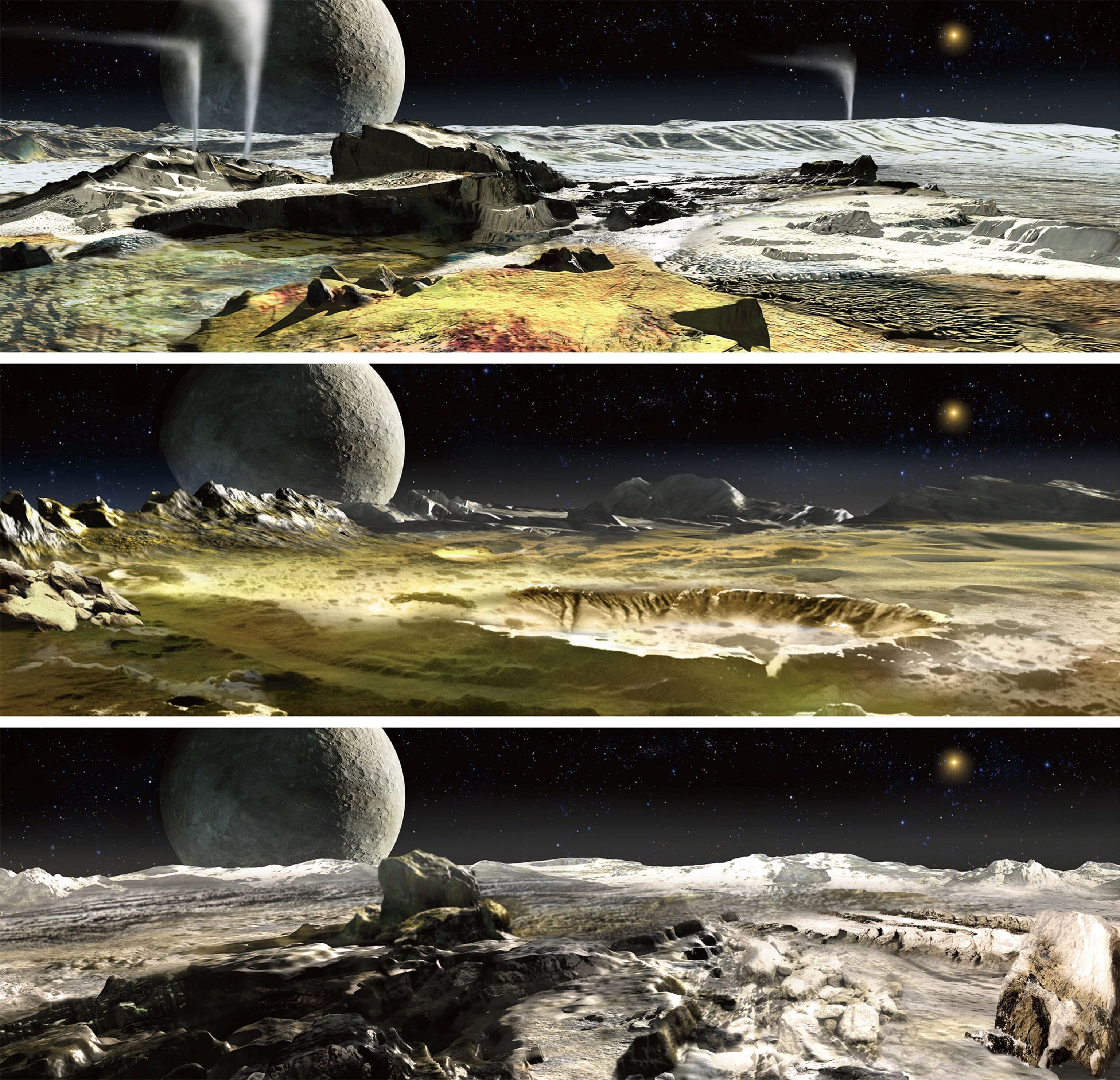

For billions of years, that faraway frosted world has kept watch over the icy wilds beyond, along with its cadre of five known moons. It’s a world that’s very much unlike Earth, but to really understand Earth’s place in our cosmic family, we need to visit Pluto. It’s the king of a thousand worlds that populate the region beyond Neptune, and a key to understanding how planetary systems form. (Learn more about the historic mission to Pluto on the National Geographic Channel.)

“Pluto is kind of a capstone of our solar system exploration, and also opening up this new realm,” says astronaut John Grunsfeld, NASA associate administrator for the science mission directorate.

At the time of the spacecraft’s closest approach, New Horizons was almost 3 billion miles from Earth.

No data were beamed home during the encounter period. Because of the way it’s designed, New Horizons has to choose between collecting data and talking to Earth—and observations trump phone calls during the close encounter. Now, scientists are still anxiously awaiting a signal from the spacecraft relaying news of a safe journey through the Pluto system.

That signal is expected to arrive around 8:53 p.m. Tuesday.

“Tomorrow morning, we should see the beginning of a 16-month data waterfall,” said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern.

Yet images from the spacecraft’s approach to the Pluto system are already revealing a world unlike anything we’ve seen before. The latest image shows a copper-colored world, mottled with extremely dark splotches and a smooth, bright, heart-shaped patch. Small impact craters sprinkle the surface, and there are hints of cliffs. (Learn more about Pluto's first close-up.)

“Pluto could have been boring, but it’s not,” says team member Mark Showalter, of the SETI Institute.

In addition to Pluto, its largest moon Charon—which forms a binary planet with the dwarf—is similarly intriguing, with a darkened pole punctuating a gray surface riven with canyons and impact crater.

Getting to Pluto

This first reconnaissance of our farthest family member is exploration on its grandest scale. It’s an endeavor more than a quarter-century in the making, kicked off by a small group of scientists who met at a Baltimore restaurant in 1989. On the table? A mission to Pluto.

Those were the waning days of the Voyager spacecrafts’ encounters with Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, and scientists were hungry for the next world in the lineup. That world, of course, was Pluto.

Over the past 26 years, multiple mission cancellations nearly brought the journey to Pluto to its knees. But when the summit is a world at the fringe of the observable solar system, obstacles are simply speed bumps, not dead-ends.

Blast Off

After years of wrangling, the $700-million mission launched in January 2006. It crossed the orbit of Jupiter a year later. New Horizons was the fastest spacecraft ever to leave Earth orbit, and at times has sailed more than a million miles a day. As it flies through the Pluto system, New Horizons will be going more than 30,000 miles an hour—so fast that the spacecraft will whiz by Pluto’s face in just three minutes.

At the time of closest approach Tuesday morning, New Horizons had traveled approximately 3 billion miles. It’s so far away that radio signals traveling at the speed of light take 4.5 hours to reach Earth. That means any two-way conversation with mission control on Earth takes at least 9 hours.

But the whole flyby, when New Horizons gets a close look at Pluto and its moons, lasts for hours. In fact, the spacecraft went silent at a few minutes before midnight on July 13. Its task, for the next 22.6 hours, was to gather as much information as possible. To do this, it executes a highly choreographed sequence of maneuvers to aim its instruments at exactly the right targets.

The observations include a fantastically complex experiment in which the spacecraft will study how Pluto’s (definite) and Charon’s (possible) atmospheres modify radio signals sent from dishes on Earth. It’s an experiment that required team members to be awake and monitoring dishes into the wee hours of the morning. Around 3:50 a.m., seven antennas began blasting Pluto with radio signals that New Horizons will collect when it reaches the other side of the planet.

“We’re going strong,” Stanford University’s Ivan Linscott said around, just after 5 a.m.

In all, the sequence will result in more than 400 observations before the spacecraft phones home, at roughly 8:53 p.m. tonight. That signal will tell mission control on Earth that New Horizons made it safely through a system that may have been studded dust and other debris that might be fatal during a collision.

The data so far has been tantalizing—intriguing photos, as well as early compositional and atmospheric data. But once the encounter data starts coming back to Earth, scientists will be drowning in all things Pluto.

"We are facing the Christmas that keeps on giving,” says deputy project scientist Kim Ennico. “This flyby is going to last 16 months!"

Follow Nadia Drake on Twitter.