Chronicling Cuba's Evolution

For 12 decades, National Geographic has reported on this Caribbean island and its often troubled relationship to the United States.

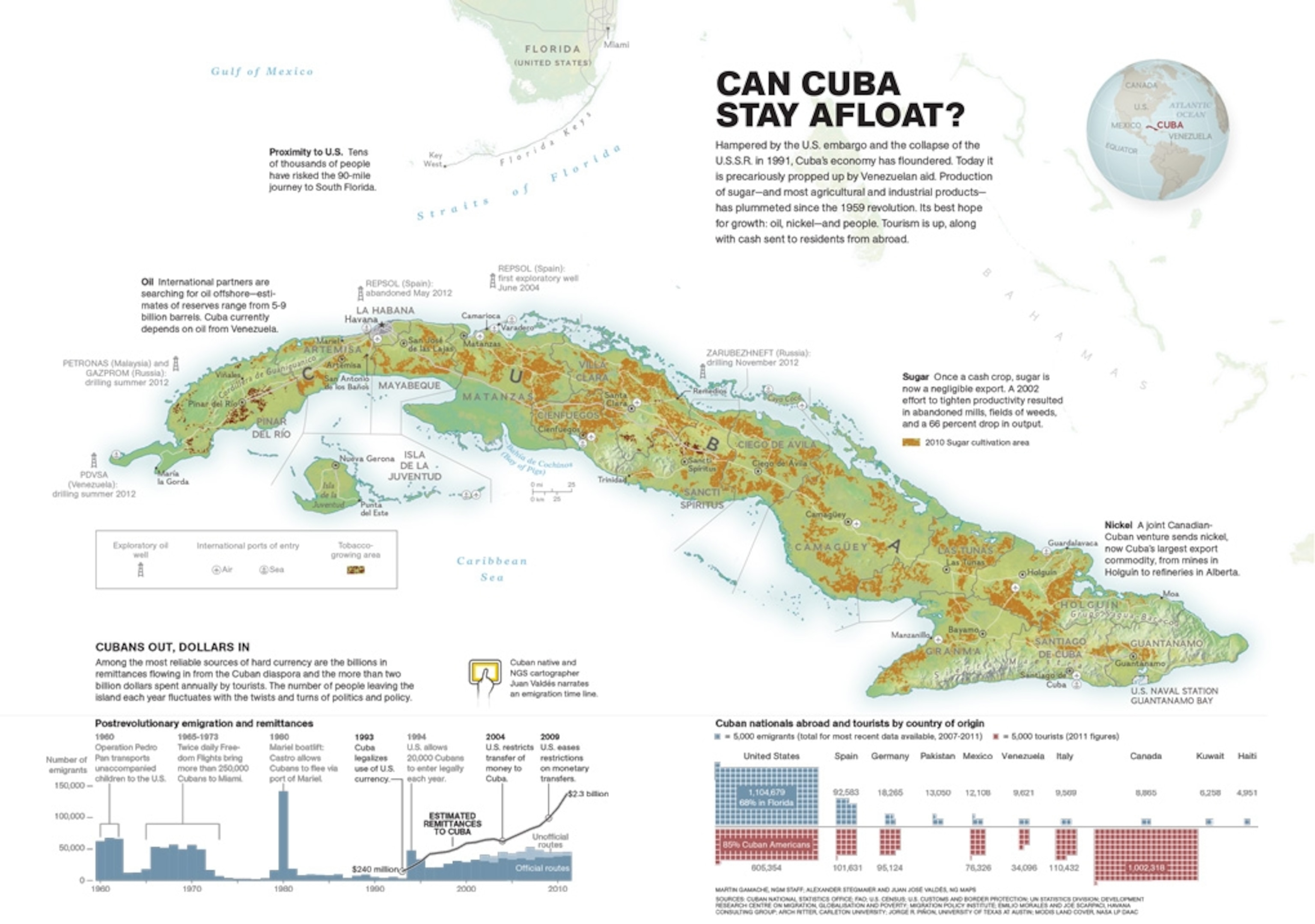

As the United States prepares to reopen its embassy in Cuba on Friday, the relationship between a world superpower and a small socialist enclave is set to change once more. Since 1897, National Geographic has published nearly 30 articles on it, the most recent aptly titled “Cuba’s New Now” (November 2012) and featuring a map that illustrates the many ways the United States and Cuba have remained inevitably entwined.

Together, these articles chronicle the island’s political and economic evolution from a Spanish colony to a socialist state, while also bringing to light its architectural and ecological treasures. In their own fashion, each article sought to convey to readers, particularly Americans, why they should—or should not—be interested in an island 90 miles from Florida.

In the first article, “The Annexation Fever” (December 1897), the author, Henry Gannett, a founder of the National Geographic Society, questioned the wisdom of the proposed acquisition of two new territories by the U.S.—Hawaii and Cuba. Although some American politicians and Cuban nationalists had called for the Caribbean island’s annexation, he countered that the Spanish colony’s lack of experience at self-government would “dilute our national legislature with a score or more of Spanish Cubans.” And he also argued that annexation could prove a costly financial misadventure.

A month after the start of the Spanish–American War, when the U.S. intervened in the three-year-old Cuban war for independence, “Trade of the United States with Cuba” (May 1898) reported on the growth of imports and exports with the island. It asserted that prior to the hostilities, which came after Spain canceled a U.S.-Cuba trade pact, imports and exports with Cuba had exceeded that with many European nations. Aside from humanitarian considerations, John Hyde, National Geographic’s editor, concluded that the reestablishment of commercial relations was justification enough for U.S. military intervention.

On January 1, 1899, the U.S. installed a provisional military government in Cuba.

“Colonial Systems of The World,” one of that month’s features, summarized the colonial policies of Great Britain and questioned how the U.S. could best open its domestic markets to its new territories—Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Hawaii.

A year later, “Our New Possessions And The Interest They Are Exciting” (January 1900) focused on a report issued by the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Statistics which estimated that only two million of Cuba’s 35 million arable acres had been cultivated. Like previous articles, this one concluded by relaying the importance of Cuba, along with the other new territories, to the U.S. economy.

National Geographic published about a dozen articles about Cuba in the first decade of the 20th century. Two months before Cuba finally achieved independence, the March 1902 issue expounded on the U.S.’s influence on the island in two articles: “American Progress in Habana” and “Cuban Railways.” The former reported on American-directed, but Cuban-funded, efforts to improve hygienic conditions in the capital. The latter focused on how the expansion of Cuba’s railway system could serve as a precursor to “her absorption into the American Union.”

Others, such as “Cuba—The Pearl of The Antilles” (October 1906), lauded the island’s geography, people and economy. It also addressed the impact of the first U.S. occupation (1898-1902). This issue reached our readers just weeks after the start of the second occupation (September 1906-January 1909). To assist them with tracking events on the island, a large-format map of Cuba was inserted.

“The rivers of sugar flowing out and the streams of gold flowing in are transforming the island that Christopher Columbus pronounced the fairest land he had ever seen into a realm where prosperity runs riot.” This line set the tone for the next dispatch from across the Straits of Florida: “Cuba—The Sugar Mill of the Antilles” (July 1920).

Breezy travelogues like, “Cuba—The Isle of Romance” (September 1933) and “Cuba—American Sugar Bowl” (January 1947) followed. The second, written by Melville Bell Grosvenor, then the editor of National Geographic, extolled Cuba’s many virtues, including, once again, sugar.

It would take another 14 years before Cuba returned to the pages of the magazine and came more than two years after Fidel Castro seized power. “Guantánamo: Keystone in the Caribbean” (March 1961), published on the eve of the Bay of Pigs invasion addressed the growing tension between the U.S. and Cuba’s post-revolutionary government. An examination of a key byproduct of that revolution would follow more than a decade later in “Cuba’s Exiles Bring New Life to Miami” (July 1973), which described a city "more than a sigh away from their beloved island across the 90-mile-wide Straits of Florida" that would become the heart of Cuba's exiled community.

“People wait in line for everything. Rationing has often been cited as proof that the economic system does not work. The official explanation: ‘It is our way of guaranteeing equality.’” So was quoted a Cuban official in “Inside Cuba Today” (January 1977).

The 1980s saw the publication of just one article—“The Many Lives of Old Havana” (August, 1989)—in which the restoration of the old city was highlighted. Here, the Cuban novelist Alejandro Carpentier's words are cited when describing the baroque facade of Havana's cathedral: "Music turned to stone."

In the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century the magazine not only reported on Cuba's evolving revolution, it also highlighted the island's non-political wonders, both architectural—“Cuba’s Colonial Treasure” (October 1999)—and ecological—“Cuba Naturally” (November 2003).

Which brings us to the last article published in the magazine. Written less than three years ago “Cuba’s New Now” features a map which highlights the links between the United States and Cuba not by mere geography, but by the emotional and economic bonds that the now nearly 2 million Cuban-Americans have with the island.

National Geographic has chronicled how the U.S. interest in Cuba has changed. But for me, as a Cuban whose family left in 1961, the phrase “bond with”— one that for the last 54 years both sides have adamantly avoided— rather than “interest in” is more fitting.

Juan José Valdés is National Geographic's Geographer and Director of Editorial and Cartographic Research. He was born in Havana and raised in the United States. He oversaw the production of the Society’s first map of Cuba in more than 100 years.