This Famous Dinosaur Could Fly—But Unlike Anything Alive Today

The animal's wings resemble those of pheasants, but it couldn't flap quite like today's birds.

The feathered dinosaur Archaeopteryx is sometimes called the “first bird” because the winged creature was the first to show an evolutionary link between birds and reptiles. But could it fly?

Paleontologists have fiercely debated this question for decades. Despite its winged form, it’s been unclear whether the animal could get airborne via its own power. Did Archaeopteryx primarily glide down from treetops? Did it flap its wings to escape grounded predators? Or did it do something different altogether?

Now, analysis of the creature’s forelimb bones finds that their structure closely resembles that of wing bones in today’s quails and pheasants, species that can fly for short bursts.

The discovery, published in Nature Communications on Tuesday, strengthens the case that Archaeopteryx could indeed take to the air. Experts are also hailing the study for its non-destructive look deep inside the fossil.

“This is a great study that uses some of the most advanced technology in the world,” says University of Edinburgh paleontologist Steve Brusatte, who wasn’t involved with the analysis.

With a Twist

Some 150 million years ago in what’s now Germany, Archaeopteryx lived among tree-speckled islands, donning a jet-black set of feathers like today’s ravens.

When the first Archaeopteryx fossils were found in the early 1860s, they created a sensation, not least of all because just a year before, biologist Charles Darwin had published his theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin had predicted intermediate evolutionary forms—and here was a link between reptiles and birds. The fossil was crowned Urvogel: the first bird.

In the years since, Archaeopteryx has been the subject of intense study, including fierce debate over its flight capabilities.

This tumultuous back-and-forth is in part due to worrying about what the fossil animal is missing—“comparing Archaeopteryx to a living bird, and commenting on what it does not have,” says Julia Clarke, a paleontologist at the University of Texas at Austin who wasn’t involved with the study.

For instance, modern flying birds have breastbones with keels, extensions where powerful breast muscles can anchor and drive the birds’ downward flight stroke. Archaeopteryx fossils haven’t been found with bony breastbones, but Clarke notes that it’s possible these structures were made of cartilage and weren’t easily fossilized.

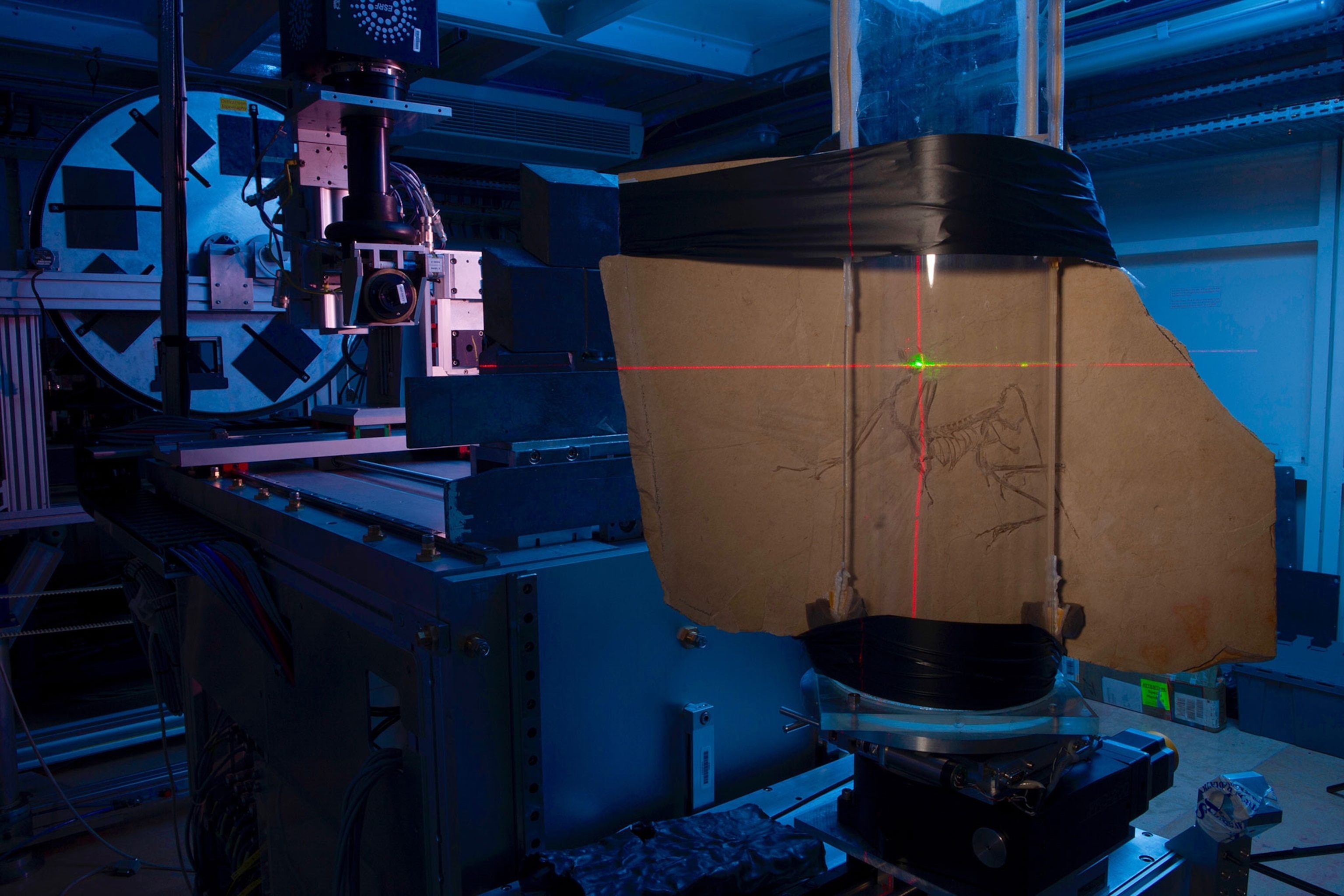

To advance the debate, researchers have increasingly put Archaeopteryx under the microscope. Few facilities are as qualified to do so as the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, home to one of the world’s most powerful x-ray scanners. (Recently, the facility confirmed that Halszkaraptor, a bizarre semiaquatic dinosaur that resembled a swan, wasn’t a forgery.)

“A lot of research had indirect evidence for flight, but it was never really substantiated,” says ESRF paleontologist Dennis Voeten, the new study’s lead author. “We decided to approach it from the other way around: We tried to actively find indicators of flight in the skeleton, rather than identify conditions that may or may not have enabled flight.”

Voeten and his colleagues subjected three of the world’s 11 known Archaeopteryx fossils to powerful x-rays. The goal was to create images of the narrowest, middle part of Archaeopteryx’s wing bones.

The researchers measured the thinness of the bones’ outer walls and they calculated what’s known as torsional resistance—their ability to resist a wringing force, like what you may apply to a wet towel and like what a bird experiences by flapping its wings. Broadly speaking, the more torsional resistance a living bird’s wing bone has, the more continuous flying the bird does.

The team then compared Archaeopteryx’s stats to those of 55 modern birds, two crocodilians, and two species of pterosaurs, the winged reptiles that lived alongside dinosaurs. Archaeopteryx’s measurements best resembled those of living birds that fly for short bursts, such as quails and pheasants.

What’s more, Voeten found that like modern birds, the Archaeopteryx skeletons had been rich with blood vessels. The discovery suggests that Archaeopteryx’s growth trends and metabolism resembled those of modern birds more than previously thought.

Different Strokes

Voeten is the first to acknowledge the academic maelstrom he’s entering, and he’s quick to point out that this study won’t be the last word on the matter.

“I’m not here to say that I’ve cracked the code, once and for all,” he says. The researchers also caution that, based on their data, Archaeopteryx couldn’t perform the modern avian flight stroke. The animal’s precise wing-flapping motion is an active area of study.

Animals like Archaeopteryx “didn't need huge chest muscles and big breastbones, but found other ways to power themselves into the sky,” says Brusatte. “And that probably means even some non-bird dinosaurs that hadn't quite yet crossed that line into birds may have been able to flap a little bit.”

For Clarke, ancient variation is to be expected. In the late Jurassic, evolution was in its sketching phase, as a menagerie of feathered dinosaurs haltingly took to the air. Only then could evolution refine flight to what it is today.

“What do we call [Archaeopteryx] if we don’t call it the Urvogel?” says Clarke. “We call it iconic.”