The big dinosaurs get all the love. I’m not even talking about the endless “my sauropod is bigger than yours” contest, or the constant effort to one-up Tyrannosaurus rex. I mean that for any given species, we’re obsessed with the biggest individual. That’s always held up as a fossil exemplar, and, from a museum perspective, if you’re going to mount a dinosaur, why not a big one?

And given that dinosaurs generally lived fast and died young, those old, super-big individuals are pretty hard to find. But we often forget the other gap in our knowledge all the way at the other end of a dinosaur’s life.

Dinosaur babies are very rare. Even for well-sampled species, hatchlings and yearlings are seldom seen. Think of Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus, for example. They’re famous dinosaurs known from dozens of individuals each, but there’s only been one itty bitty baby published for each of these Cretaceous celebrities. For most dinosaur species, we haven’t yet found infants.

The discovery of any baby dinosaur, therefore, is a reason to thank our luck that the fossil record has safeguarded the rarity since the Mesozoic, and a new paper from Leonard Dewaele and colleagues gives us just such an occasion to celebrate.

Saurolophus angustirostris is one of those dinosaurs that’s known from a pretty good sample. Found in the Gobi Desert’s Nemegt Formation, this duck-faced herbivore is known from various sub-adult and adult individuals. The babies have remained elusive, however, no thanks to poachers.

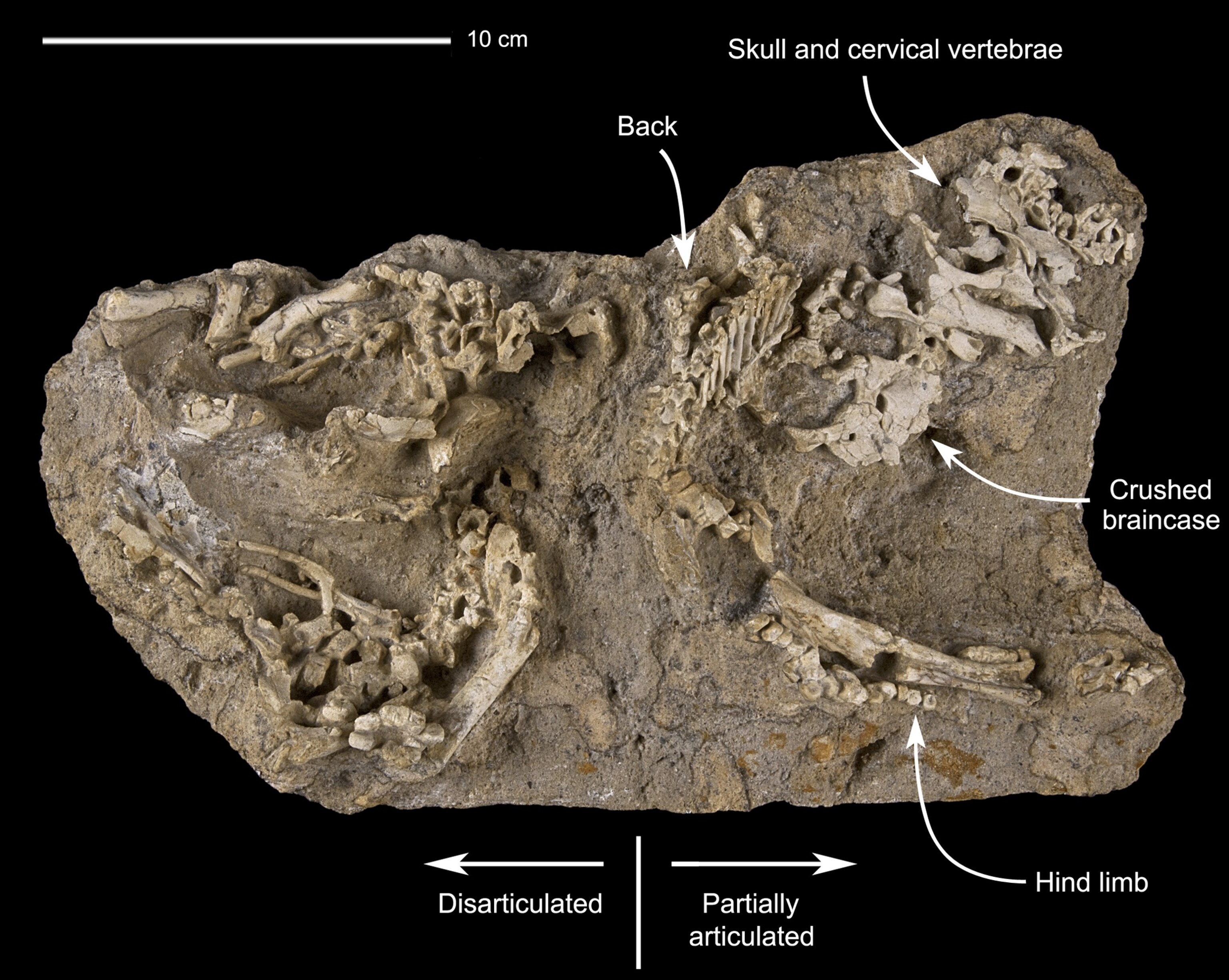

The block at the center of the new study from Dewaele and colleagues was stolen from a Mongolian locality called “The Dragon’s Tomb” sometime during the 20th century and moved through private collections in Japan and Europe. Thankfully, however, in 2013 the fossils were donated to the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels before being repatriated to Mongolia. Now that the block has a proper home in a museum, the story of the baby Saurolophus can be told.

At least three baby hadrosaurs are buried in the block, entombed with bits of eggshell that once surrounded them. That’s a lucky break. This simple association will help paleontologists identify other Saurolophus eggs in the future now that bones and eggs have been found together. And the little dinosaurs are tiny compared to the adults. The skulls of the incubating Saurolophus are only about 5% the length of the largest known for their species—adults could reach almost 40 feet in length. Even big dinosaurs started small.

Whether or not the little Saurolophus had pushed their way out of their eggs yet isn’t clear. They died when they were “perinatal,” or around hatching age.

What we do know is that they would have been adorable. These little dinosaurs weren’t copies of their parents, but awkward little critters with big heads, large eyes, and, inside, many of their bones were still fusing. Their saurian kind might have ruled the world, but these Saurolophus were tiny squeakers that probably tottered around the nest for a while before exploring the wider Cretaceous world. It may be strange to say given the group’s reputation as the “terrible lizards,” but dinosaurs started life cute.

Reference:

Dewaele, L., Tsogtbaatar, K., Barsbold, R., Garcia, G., Stein, K., Escuillie, F., Godefroit, P. 2015. Perinatal specimens of Saurolophus angustirostris (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae), from the Upper Cretaceous of MongoliaPerinatal specimens of Saurolophus angustirostris (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae), from the Upper Cretaceous of MongoliaPerinatal specimens of Saurolophus angustirostris (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae), from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. PLOS ONE. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138806

Top image:

Bell, P. 2012. Standardized terminology and potential taxonomic utility for hadrosaurid skin impressions: a case study for Saurolophus from Canada and MongoliaStandardized terminology and potential taxonomic utility for hadrosaurid skin impressions: a case study for Saurolophus from Canada and MongoliaStandardized terminology and potential taxonomic utility for hadrosaurid skin impressions: a case study for Saurolophus from Canada and Mongolia. PLOS ONE. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031295