Every few months another press release heralds some breakthrough in the search for extraterrestrial life. Usually, they are just teases. There must be life elsewhere – what a horrible waste of space the universe would be if there was not! – but these papers tell us more about what we expect to find than what may actually exist. We can hypothesize, speculate, and wonder about what alien life might be like and what such organisms would tell us about evolution on our own planet, but, so far, the sought-after solid evidence has remained elusive.

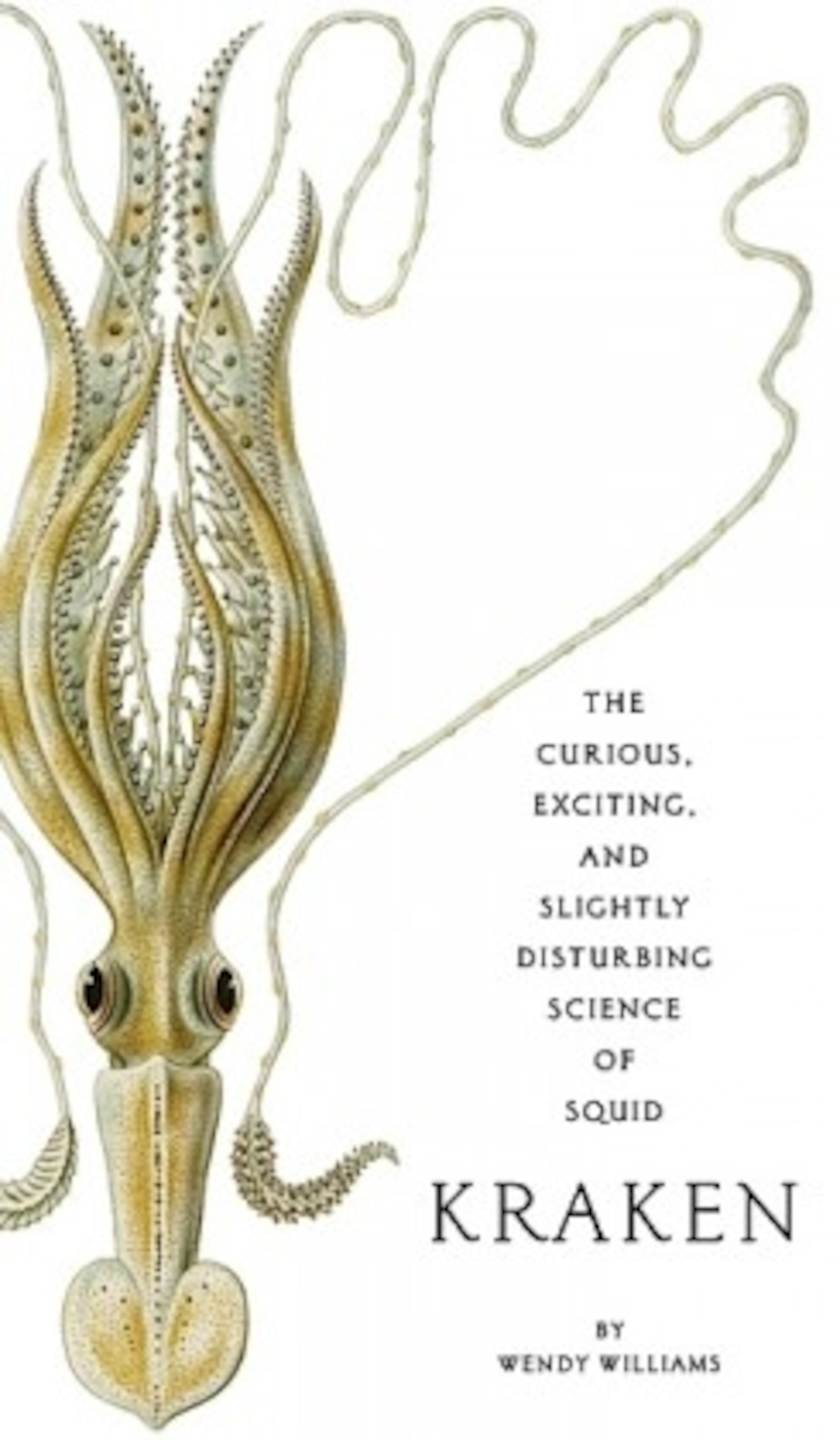

But we need not look to outer space to find “alien” life that can teach us about the convoluted nature of evolution. Consider the squid. These cephalopods – so diverse and disparate that the archetype associated with the word “squid” does not do them justice – last shared a common ancestor with us over 555 million years ago, yet they share some curious traits in common with our species. Though their squishy, tentacle-tipped bodies are obviously quite different than our own, the anatomy of their brain cells and eyes are eerily similar to the corresponding structures in our bodies – products of convergence made possible by evolutionary quirks in the deep past. We can learn quite a bit about ourselves by investigating the anatomy and history of squid, and this is just what Wendy Williams sets out to do in her new book Kraken.

Williams’ book is not a comprehensive tour of squid natural history. Instead, Kraken is as an exploration of how we perceive squid, octopus, and cuttlefish. Only a handful of species – primarily the giant squid, the Humbolt squid, the longfin inshore squid, and the Pacific giant octopus – receive much detailed attention. These relatively familiar cephalopods act as molluscan ambassadors for the rest of their kind, and Williams uses them the draw out the general characteristics that make these creatures seem so strange.

Though a few squid get featured before it, the famous giant squid Architeuthis plays a prominent role in a few early chapters. This enormous squid is the stuff of legend, and even today the true nature of this creature remains mysterious. Even simple facts such as how many species there might be and how the squid capture prey are debated, much less surprises such as why giant squid should have chromotaphores inside their bodies or why they have relatively low levels of toxins in their flesh for apex predators. To call them sea monsters may be a bit sensationalistic, but scientific study has not diminished their enigmatic nature.

In later chapters, Williams joins squid experts and neuroscientists to explore the similarities between nerve cells in our brains and those in squid. The longfin inshore squid Loligo pealei has very large nerve cell parts called axons, and, since the squid axons are large and are relatively easy to dissect, training neuroscientists often practice by removing them from the plentiful cephalopods. Their study has also been involved in scientific breakthroughs such as the development of video-enhanced microscopy by Strömgren Allen and Robert Day Allen in the 1980’s. These chapters are followed by a few sections in the company of the Pacific giant octopus – a cephalopod so clever that it has raised deep questions about how we define and test intelligence in other species.

Williams guides her readers over squid-filled boat decks, by aquarium tanks, and into dissection labs during her journey to understand cephalopods, but the narrative she creates is uneven. She is at her best when writing in the first person or recounting her conversations with researchers, but there are other explanatory portions of the book that simply fall flat. An early subsection about the evolutionary history of squid feels more like a Wikipedia article than part of a book, and long stretches of historical narrative in the neuroscience portion of the book feel tangential to the main storyline. Williams ends the book strong by considering what investigations of cephalopod intelligence might tell us about our own ability to understand the mental lives of other animals, though, and the portions of the book about the Humbolt and giant squid truly shine.

In one of Kraken’s early chapters, Williams relays part of her conversation with Smithsonian squid expert Clyde Roper. Roper, bemoaning the difficulty in finding funding for ocean research, said “We know more about the moon’s behind than we do about the ocean’s bottom.” He has a point. Though cosmology, space exploration, and related efforts are certainly fascinating, there is much we don’t know about our own planet and the life that exists on it. Even though we may hope to find other planets similar to our own inhabited by life forms that will provide some context for our own existence, we would be foolish to ignore the fact that there are mysteries on our own planet relevant to questions about how life as we know it came to be. Squid represent a long-lived lineage so different from our own as to almost be alien, yet we know we share a deep history with them. That is a marvelous thing, and perhaps, by better understanding the peculiar cephalopods, we may learn a few things about ourselves.

Top Image: The famous diorama of a giant squid fighting with a sperm whale at the American Museum of Natural History. Image from Flickr user el.hoyinator.