1 of 9

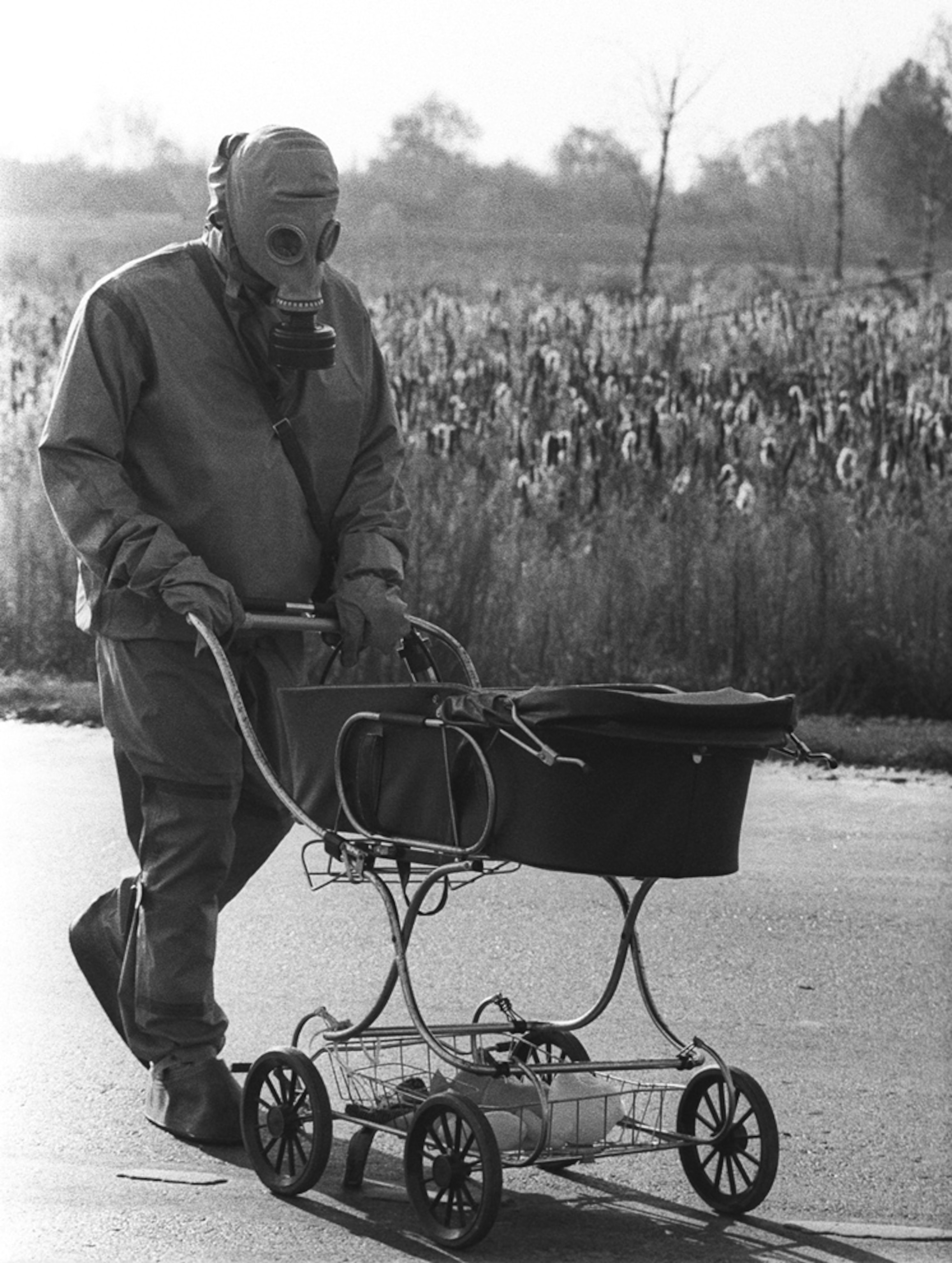

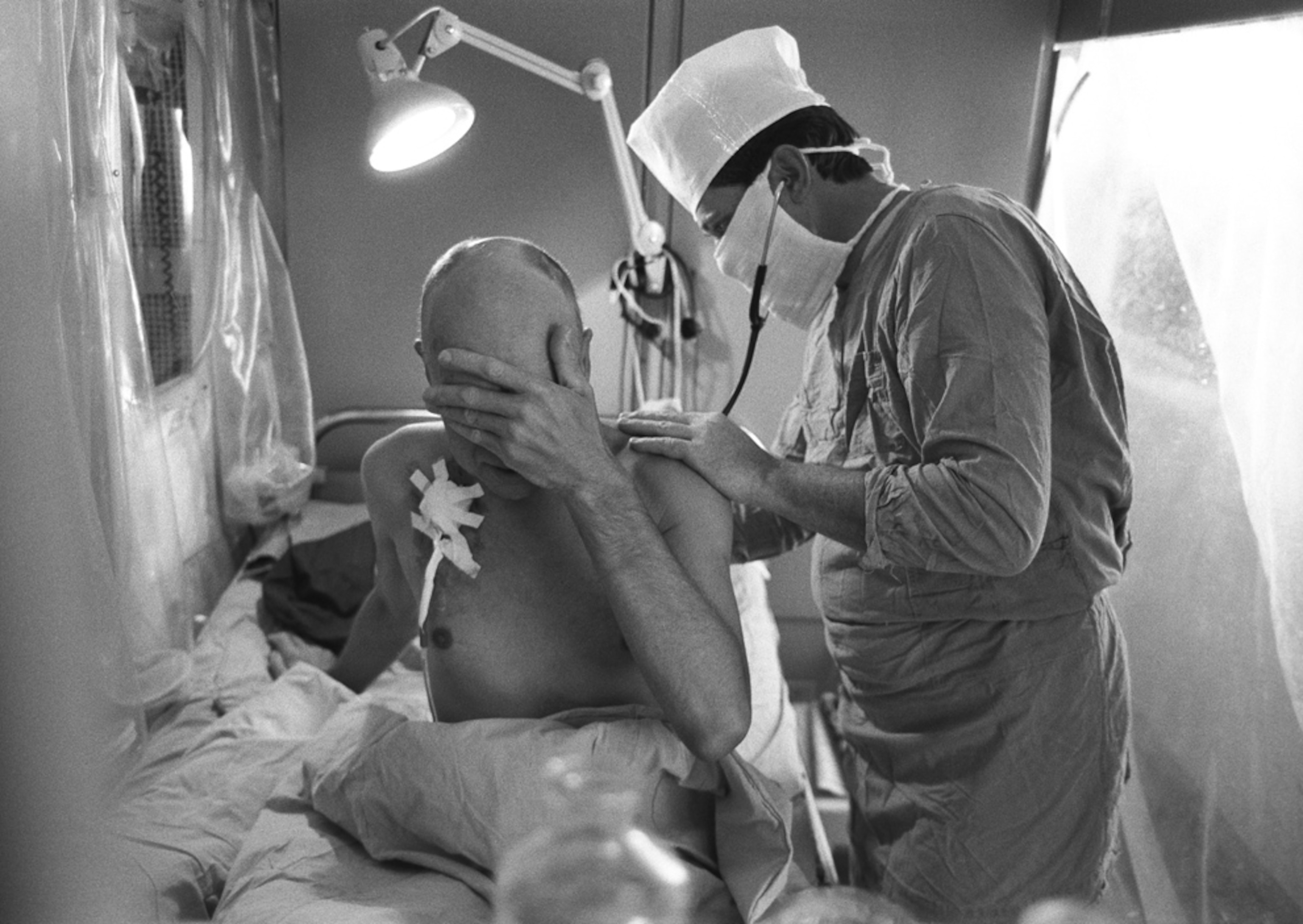

Photograph by Igor Kostin, Sygma/Corbis

Pictures: "Liquidators" Endured Chernobyl 25 Years Ago

Robots couldn't handle the intense radiation at Chernobyl, so the dangerous nuclear cleanup job fell to the "liquidators" — a corps of soldiers, firefighters, miners, and volunteers.

Published April 28, 2011