New megaraptor discovered—with its final meal still in its mouth

A croc bone locked between the 70-million-year-old predator’s jaws gives scientists a rare look into its life and possibly its last feast.

While the great Tyrannosaurus rex stalked prehistoric North America, a very different apex predator prowled ancient Argentina: the newly discovered megaraptor Joaquinraptor casali.

When paleontologists excavated the dinosaur, they made a tantalizing find. Clenched within its massive jaws was a Cretaceous crocodile’s arm bone. The discovery offers a glimpse into what may have been the carnivore’s last meal some 70 million years ago.

“Fossilized behavior, if that’s really what this is, comes along so rarely that you’ve just got to celebrate it when it does,” says Matthew Lamanna, a paleontologist from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, and a National Geographic Explorer.

In addition to the megaraptor’s skull, Lamanna's team also unearthed its arms, parts of its legs, a smattering of ribs, vertebrae, and other petrified pieces. They estimate that Joaquinraptor stretched more than 23 feet long and weighed over a ton. It likely snapped at prey with its elongated snout and snatched snacks with its stout arms tipped in impressively long, curved claws. Lamanna and his colleagues described the new species Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

Joaquinraptor, despite being represented by just a partial skeleton, is among the most complete megaraptors yet found. Finding one of these rare dinosaurs with a potential meal still in its jaws is even more unexpected. Fossils that reveal what prehistoric animals ate are uncommon. When they do turn up, they provide important clues to the lives and ecology of extinct species. Paleontologists have seen this a few times before, such as in tyrannosaurs with a taste for drumsticks and a mosasaur with fish chunks in its guts. Sharp teeth can tell us that megaraptors ate meat, but these preserved table scraps can show what was on the menu.

Mysterious megaraptors

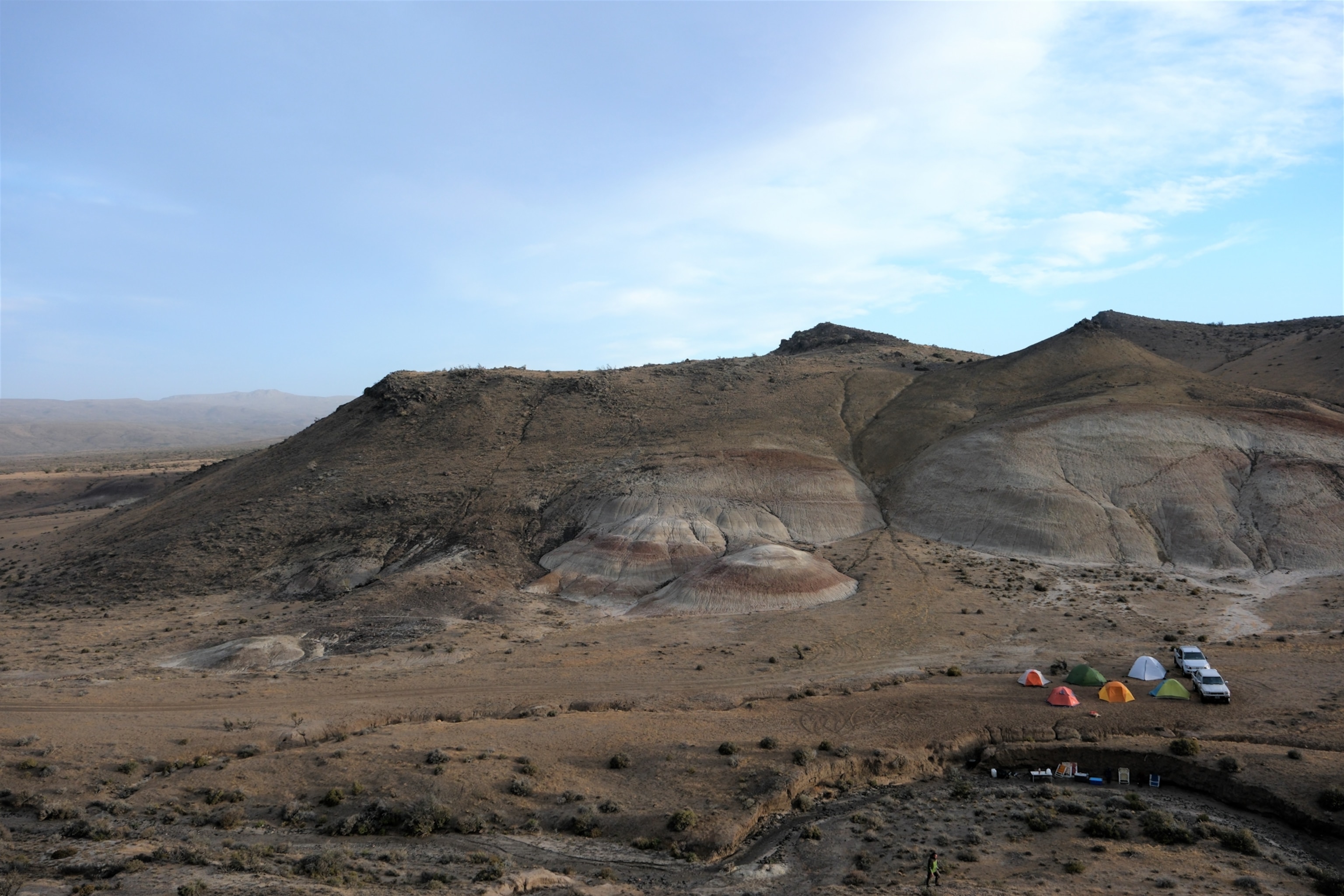

In 2019, Lucio Ibiricu, a paleontologist from the Instituto Patagónico de Geología y Paleontología in Argentina, was prospecting the Cretaceous rocks of Chubut Province in central Patagonia for new fossil sites. During the search, his colleague Bruno Alvarez saw a small bone fragment jutting from the rock. The spot looked promising, and so a few months later the researchers returned to carefully uncover whatever lay hidden within.

“At this moment, we realized the discovery was one of the most important for the team,” Ibiricu says. The skull bones and arm bones left no doubt the fossil belonged to a megaraptor, an enigmatic group of predatory dinosaurs that lived in prehistoric Asia, Australia, and South America.

These dinosaurs have confounded paleontologists since the genus Megaraptor itself was named in 1998. As the name implies, they are larger than so-called “raptors” like the turkey-sized Velociraptor. The dinosaurs had long, low snouts and stout arms with large, intimidating claws. Paleontologists hypothesize that they were close relatives of tyrannosaurs but thrived in habitats where tyrannosaurs were absent. To date, most megaraptor species are only known from fragmentary remains.

“Megaraptorans are mysteries primarily because most of their fossils are so beaten up,” says Lamanna. The fossils are “complete enough to show us that these extraordinary predatory dinosaurs were out there but not complete enough to tell us a ton about them.”

While the earliest megaraptors date to about 132 million years ago, Joaquinraptor was one of the last. It lived sometime between 70 and 66 million years ago, at the very end of the Cretaceous before the asteroid-triggered extinction that ended the heyday of the dinosaurs.

“The new discovery offers interesting novelties about the survival of megaraptorid dinosaurs up to the very end of the Mesozoic,” says Fernando Novas, a paleontologist from the Bernardino Rivadavia Natural Sciences Argentine Museum. Novas previously discovered the megaraptor Maip macrothorax also in Argentina, but was not part of the team that discovered Joaquinraptor. The new species, he notes, indicates that megaraptors were numerous and diverse in South America right up to the end of the Cretaceous.

Dinosaur's last supper?

Joaquinraptor was undoubtedly an apex predator that hunted through the inland woodlands of southern Argentina. But was it really chowing down on crocodile right before it perished?

It’s possible the croc bone ended up in between the megaraptor’s jaws by coincidence. But if rushing water had mixed together the remains of multiple creatures, the fossil site would have been a jumble. Instead, the arm bones of Joaquinraptor were found in partial articulation, close together and some still connected. The near-life positioning of these bones suggests that the water flow that buried the fossil was not particularly strong and therefore less likely to have carried in other bones from the surrounding area.

Studies are ongoing, the team says, but the way the dinosaur’s bones came to rest hint that the croc was food rather than a chance inclusion. But if it is just coincidence “then Mother Nature is playing a cruel joke on Lucio, myself, and our coauthors, because several things about this dino-croc association are super weird,” says Lamanna.

Ibiricu adds that there were no bones other than the crocodile’s found near Joaquinraptor, increasing the chances the dinosaur was indeed buried with its last meal.

“This is a sensational aspect of the discovery,” says Novas, “and I imagine that it may constitute a photographic snapshot of the ecological interaction among two different predatory groups.”

Just last month, Novas and colleagues described a new late Cretaceous crocodile named Kostensuchus atrox from rock layers dating somewhat around the time of Joaquinraptor, making it perhaps the very kind of croc that became a morsel in this megaraptor’s mouth.