How We've Tackled the Evolving Science of DNA

“No article we have ever published has been more difficult” than our first feature about the molecule of life, which appeared 42 years ago.

On April 25, 1953, the journal Nature published a picture that sparked a revolution: the first drawing of the structure of the DNA molecule. That landmark discovery, made possible by the x-ray crystallography work of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins, put Francis Crick and James Watson at the forefront of the burgeoning field of molecular biology.

Within weeks, the New York Times proclaimed that the discovery “should make biochemical history,” and in the years since, news outlets have published reams about DNA and its importance to unraveling the way life works.

But for its part, National Geographic didn't make the plunge into molecular biology until 23 years after the discovery of the double helix.

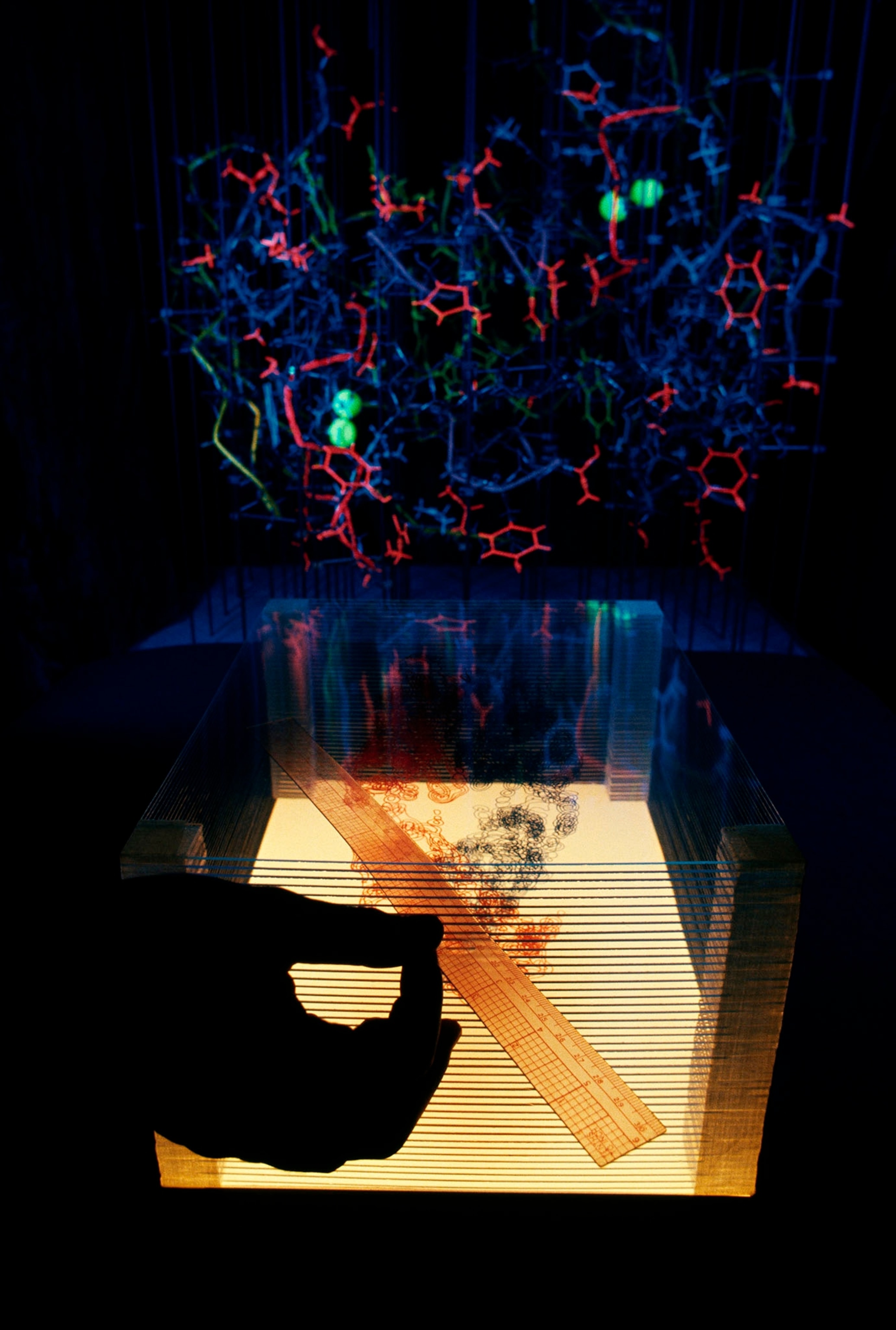

For a magazine that had long prided itself on place-driven narratives and photography, grappling with the microscopic world of “the new biology” pushed National Geographic staff at the time to the point of discomfort. It took the magazine more than two years to assemble its first foray into molecular biology, a splashy feature titled “The Awesome Worlds Within a Cell” that ran in the September 1976 issue.

Rereading the story today, the relieved sigh the staff must have made as the story went to press is almost palpable.

“No article we have ever published has been more difficult, either in the amount of effort and skill that went into its preparation, or in the perseverance readers must bring to it if they are to understand this complex new face of science,” Gil Grosvenor, then National Geographic's editor-in-chief, wrote in an accompanying letter to readers.

A Solid Base

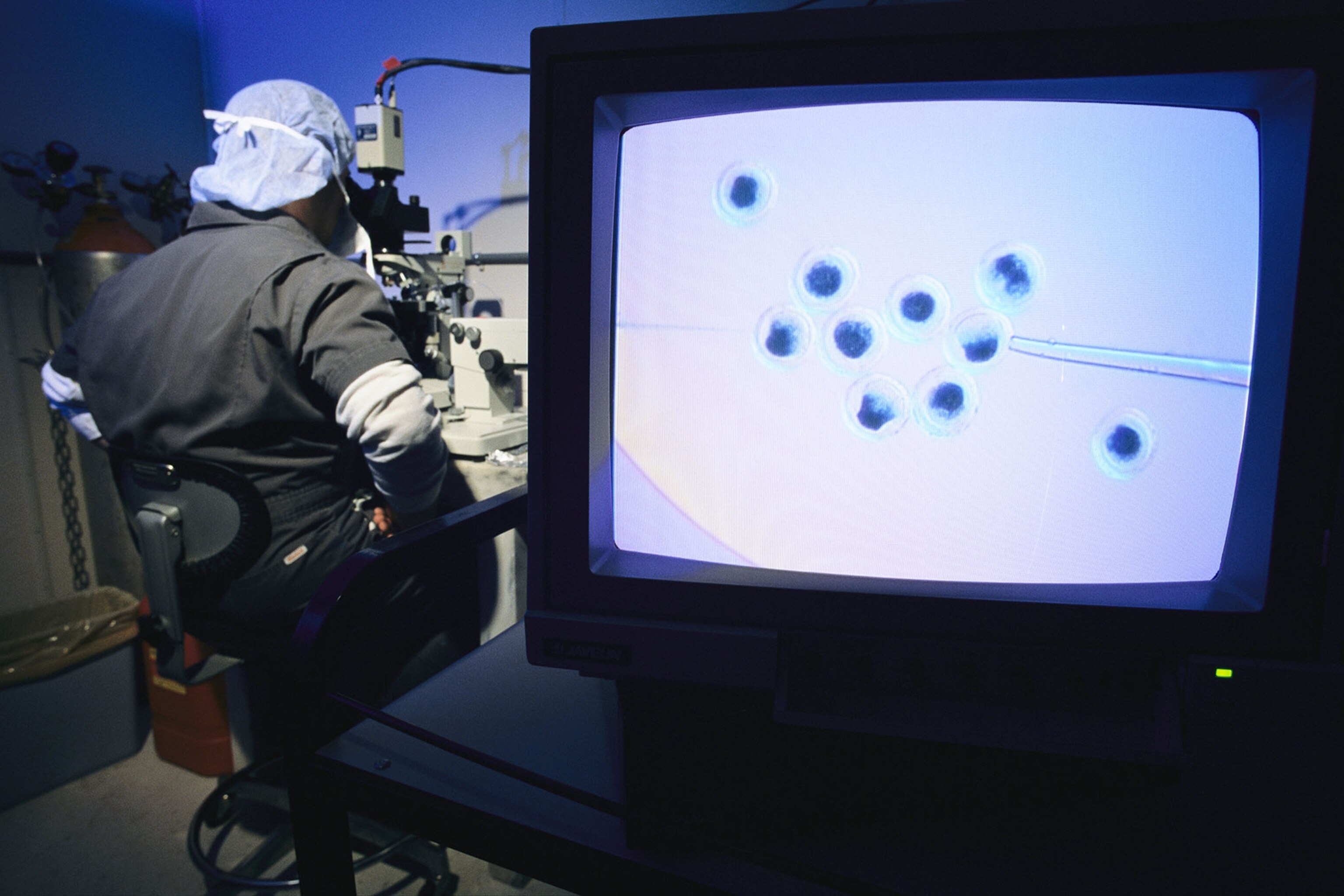

In a sense, the story helped mark National Geographic's transition to an institution that increasingly tackled the complexities of science in all forms—including an ongoing exploration of the wonders and challenges of unlocking DNA. The molecule makes a guest appearance, for instance, in a 1977 story about new microscope technologies. And in December 1984, geneticist Robert Weaver—the son of longtime National Geographic editor Kenneth Weaver—penned a feature about the then-nascent field of biotechnology, kicking off decades of coverage involving this rapidly advancing science.

As readers learned, the increasingly versatile DNA toolkit could trace the origins of elephant ivory, identify ancient diseases in long-dead mummies, help unravel the mysteries of aging, and even chart life's story back to its very origins. The double helix was also being employed to study endangered species and act as a “fingerprinting” technique for identifying each individual on the planet.

As the coverage progressed, so too did readers' familiarity with the language of genetics.

“You started hoping for the day when you didn't have to take a paragraph to say, This is the stuff of the double helix, and this is how traits are inherited,” says Jamie Shreeve, a National Geographic contributing editor and former executive editor for science. “My career spanned the time from when you always had to do that to when you almost never had to do that. That's a cool thing.”

Shreeve is arguably one of National Geographic's most influential genetic chroniclers. As a freelance journalist, he wrote a sweeping 1999 feature about the race to decode the human genome, following it up in 2006 with a story on “our greatest journey”: the genetic trails Homo sapiens have ventured on across millennia. Shreeve and others reinvented how to describe DNA to nonspecialist audiences—trying to push beyond the “blueprint” metaphors so often used before.

“The genome is really like a piano keyboard: Each key plays a note, and that note is a protein that that gene is expressing,” says Shreeve. “What matters is how these genes are combined into different chords and scales and melodies and harmonies that create the processes of all life. There's jazz frogs and classical snakes and country-music dinosaurs—there's just one kind of heredity molecule, but it does so many different things.”

However, more than two-thirds of the magazine's mentions of “DNA” occur after 2003, which saw the publication of the first full sequence of the human genome as part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health's Human Genome Project.

With this powerful tool for understanding our own genetic code, DNA could provide clues to the identity of the Phoenicians, and could allow scientists to peer deeper into the lives of the powerful Medici family, whose remains were exhumed in 2004. The magazine also made clear that the “genetic revolution” provided further backing in the overwhelming case for evolution. “We've come a long way since Darwin looked for evidence in his pigeon coop,” the writer drolly notes.

The magazine isn't the only forum in which National Geographic has explored DNA. In 2003 and 2005, television documentaries traced the human journey back some 60,000 years to a major migration out of Africa. Books ranging from science encyclopedias to primers on genealogy have explained genetics to readers of all ages.

What's more, National Geographic's grant-giving arm has supported ongoing genetics research. In the last five years, the National Geographic Society has given more than 200 grants to researchers, artists, and storytellers whose work touches on genetics. And National Geographic's Genographic Project, launched in 2005, has worked with nearly a million people to create the largest anthropological genetic survey of its kind. (Find out more about the Genographic Project.)

Strands of Wisdom

With knowledge comes perspective, and as genetics has matured as a science, so too has National Geographic's handling of its ethical implications.

If scientists develop genetic techniques to resurrect extinct species, should they use them? Are the techniques of criminal forensics, including the genetic ID of suspects, really as scientifically grounded as many, including National Geographic, have made them out to be? What is the proper role of industry in genetics research? How should scientists wield the extraordinary power of the gene-editing technique CRISPR?

Above all, how are people not defined by their genes? As National Geographic's April 2018 special issue makes clear, there's no genetic basis for the concept of race. “Of course, just because race is 'made up' doesn't make it any less powerful,” writes science journalist Elizabeth Kolbert in the special issue. “To the victims of racism, it's small consolation to say that the category has no scientific basis.”

There are still many truths about the human experience that DNA can help illuminate. For one, Shreeve says, future research will likely stress that the human journey was never at rest. “This typological sort of thinking of people in blocks that, actually, National Geographic’s history helped promote—that’s wrong,” he says. “What we know now is that all populations are fluid.”

Shreeve's gaze into the future also drifts toward the heavens. “If we find [extraterrestrial] life, is it going to be DNA-based, and if it's DNA-based, does that mean it's related to our kind of life ... or is it because DNA has something essential that happens anywhere?”

With so much yet to discover, Shreeve, like Grosvenor before him, emphasizes that National Geographic will always have a place exploring the awesome worlds within the cell.