In a dazzling discovery, fossils brought up from a mine in Wee Warra, near the Australian outback town of Lightning Ridge, belong to the newly named dinosaur species Weewarrasaurus pobeni. The animal, which was about the size of a Labrador retriever, walked on its hind legs and had both a beak and teeth for nibbling vegetation.

A type of dinosaur known as an ornithopod, Weewarrasaurus may have moved in herds or small groups for protection. The fossil adds to growing evidence that the plant-eating fauna of the Southern Hemisphere consisted of quite different creatures than the Cretaceous herbivores of North America, such as the numerous horned relatives of Triceratops and the duck-billed hadrosaurs.

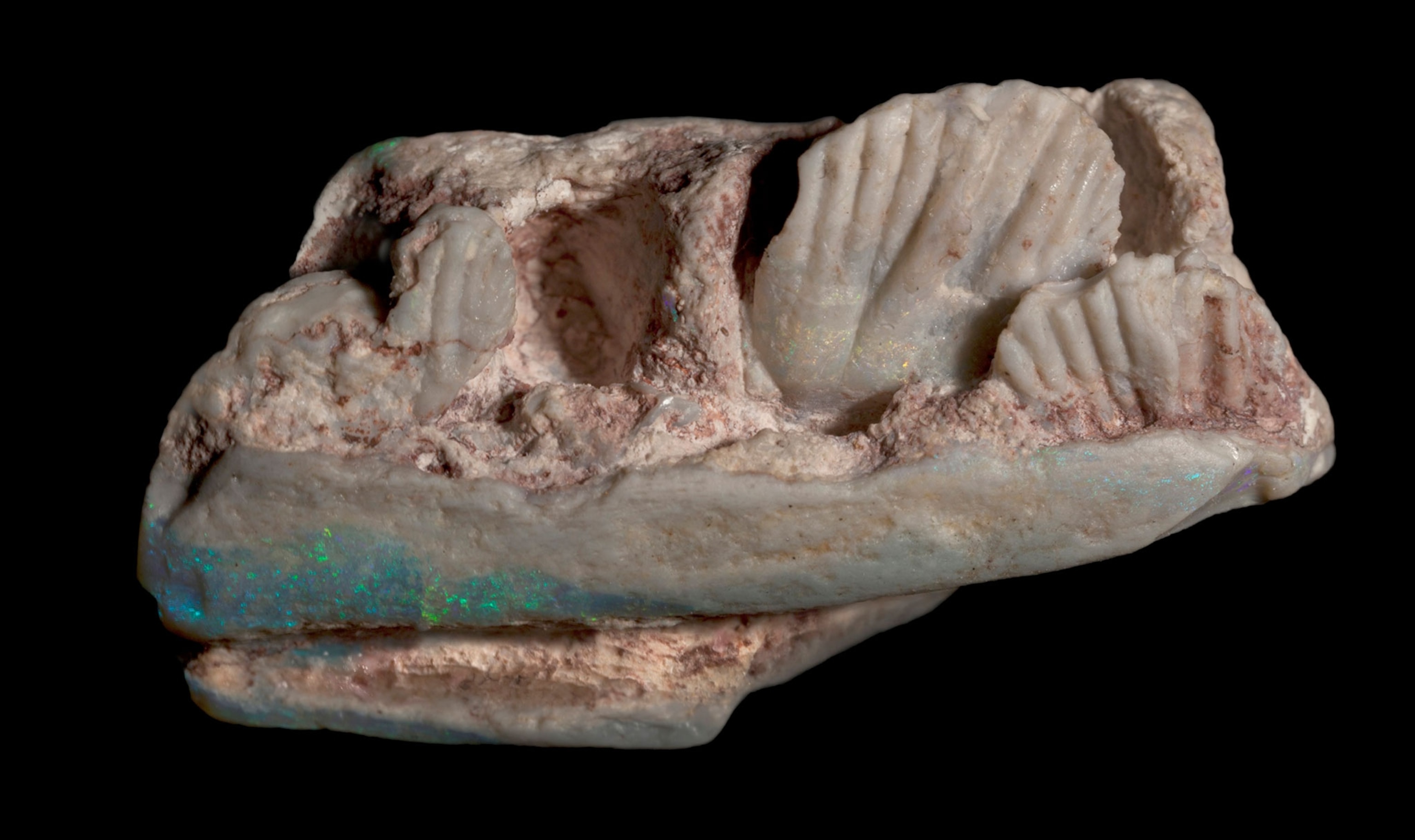

But perhaps the most striking thing about this fossil—described today in a paper published in the journal PeerJ—is that it is made from opal, a precious gemstone that this part of the state of New South Wales is known for.

“As a paleontologist I am interested, really, in the anatomy—the bones, and in this case, the teeth,” says lead author Phil Bell of the University of New England in Armidale, New South Wales.

“But when you’re working in Lightning Ridge,” Bell says, “you can’t ignore the fact that some of these things are preserved in spectacular opal that’s all the colors of the rainbow.”

Like no place on Earth

Hundreds of small mines pockmark this arid landscape 450 miles northwest of Sydney. But dinosaur fossils are found here only rarely, so Bell says it is miraculous to have uncovered a fossilized jaw with teeth. (See photos of an opal mining community that lives underground in South Australia.)

“It’s a truly unique area,” he adds. “There’s no place in the world like this, where you have dinosaurs preserved in beautiful opal.” This nearly 100-million-year-old specimen is hewn from the brightly colored gemstone, which formed over the course of eons from the concentration of silica-rich solutions underground.

The fossil was found in 2013 by Adelaide-based opal dealer Mike Poben, for whom the new species was named. He had bought a bag of rough opal from miners and picked through it for fossils, as he always does. One unusual piece caught his eye.

“A voice in the back of my head said, teeth,” he recalls. “I thought, Oh my God, if I have teeth here, then this is a jawbone.”

Poben held on to the potentially toothy specimen and sent the remaining opal out with a so-called runner, whose job it was to drive around Lightning Ridge trying to find a buyer. After nine days, the runner returned the bag unsold, so Poben had a further look through its contents.

“I found another piece of bone, smaller with sockets, turned it over, and then things really started exploding in my head,” he says. “When I lined the pieces up, I realized I had two pieces from the same jawbone.”

Bell, the paleontologist who would go on to formally describe the dinosaur, says his own jaw dropped the first time he saw the highly valuable fossil with its distinctive teeth in 2014. Poben subsequently donated the fossil to the Australian Opal Centre, a Lightning Ridge museum with the world’s largest collection of opalized fossils.

Dinosaurs of the southern supercontinent

Weewarrasaurus adds to a rapidly growing roster of dinosaurs from the eastern part of the southern supercontinent of Gondwana. While there are fewer than 20 named Australian dinosaurs, this is the fourth species described since 2015, including a sauropod, Savannasaurus; an ankylosaur, Kunbarrasaurus; and another small ornithopod, Diluvicursor.

What is today a dry, dusty environment dotted with shrubby vegetation couldn’t have been more different at the time Weewarrasaurus lived there. During the mid-Cretaceous, Lightning Ridge was a lush area of lakes and waterways on the fringes of the prehistoric Eromanga Sea.

At that time, it was also at a latitude of 60 degrees south, much nearer to the Antarctic Circle. Lightning Ridge would have been about as near to the South Pole as the Finnish capital of Helsinki is to the North Pole today. The area had a temperate climate that rarely dipped below 40 degrees Fahrenheit but experienced long, dark winters, with days when the sun rose above the horizon only briefly.

“Fossils from the ridge are helping illuminate the faunas of eastern Gondwanaland,” which at that time, 96 to 100 million years ago, covered perhaps a fifth of the world’s land area, says paleontologist Ralph Molnar with the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff.

When people think about Cretaceous dinosaurs, species from western North America usually dominate the picture. But “the tyrannosaur-ceratopsian-hadrosaur fauna” seems to be something that was specific to North America and Asia,” says Molnar, who was previously based at the Queensland Museum, where he was involved in the 1981 discovery of Muttaburrasaurus, Australia’s most famous dinosaur.

By contrast, the Southern Hemisphere’s dinosaur fauna had a very different composition. And differences even between South America (then western Gondwana) and Australia are now coming into focus, he says.

“One specific difference from South America is the abundance and diversity of small ornithopods in Australia.”

An abundance of ornithopods

Fossil fragments reveal that there were up to three species of small ornithopod at Lightning Ridge, Bell’s team reports in the paper, while four more are known from the state of Victoria.

In North America, small ornithopods lived alongside larger horned ceratopsians and hadrosaurs, which are “are at the top of the evolutionary ladder in terms of chewing up vegetation,” Bell says. Small ornithopods such as Thescelosaurus may have found it hard to get a toehold there and so were never a major feature of ecosystems. But Triceratops and its relatives, along with the duck-billed species, never made it to Australia.

“So here, small ornithopods had free range to feed on as much vegetation as they liked and evolved into many different species,” Bell posits.

“The new discoveries can help us understand the connections, possible migrations, and the relationship of the small bipedal herbivorous dinosaurs of South America, Antarctica, and Australia during the Cretaceous,” says Penélope Cruzado-Caballero, an expert on herbivorous dinosaurs at the National University of Río Negro in Argentina.

While today’s continents that once made up Gondwana had already then begun to drift apart, the fact that her team has found fossils of related ornithopods in Antarctica and Argentina “tells us that during the Cretaceous, there had to be bridges that connected these continents at least intermittently,” she says. “Did the South American fauna migrate to Australia through Antarctica, giving rise there to the Australian ornithopods? Or was it the other way around?”

New fossils may help fill these gaps in knowledge, and Bell and his team are even now working on a series of other opalized specimens likely to be described as new species in coming years.