This bizarre ancient worm had spiky teeth and a retractable throat

Scientists found the 500-million-year-old fossil of a "penis worm" in the Grand Canyon—and reconstructed how the creature would have used its strange mouth to feed.

In September of 2023, Giovanni Mussini, a paleontologist and doctoral student at the University of Cambridge, joined an expedition into the vast depths of the Grand Canyon. He and other researchers rode a dinghy down the turbid Colorado river, stopping occasionally to scale dangerously flaky rocks in search of 500-million-year-old fossils from the Cambrian period, the dawn of complex animal life.

The results of that expedition, reported July 23 in Science Advances, included the miniscule remnants of brine shrimp-like crustaceans and snail-like mollusks. But the most interesting findings—uncovered as Mussini dissolved Grand Canyon rocks in acid and combed them for fossils—were two types of tiny mystery teeth. One set was sharp. The other had feathery projections coming out of its sides. Both, it turns out, belonged to an obscene-looking monster.

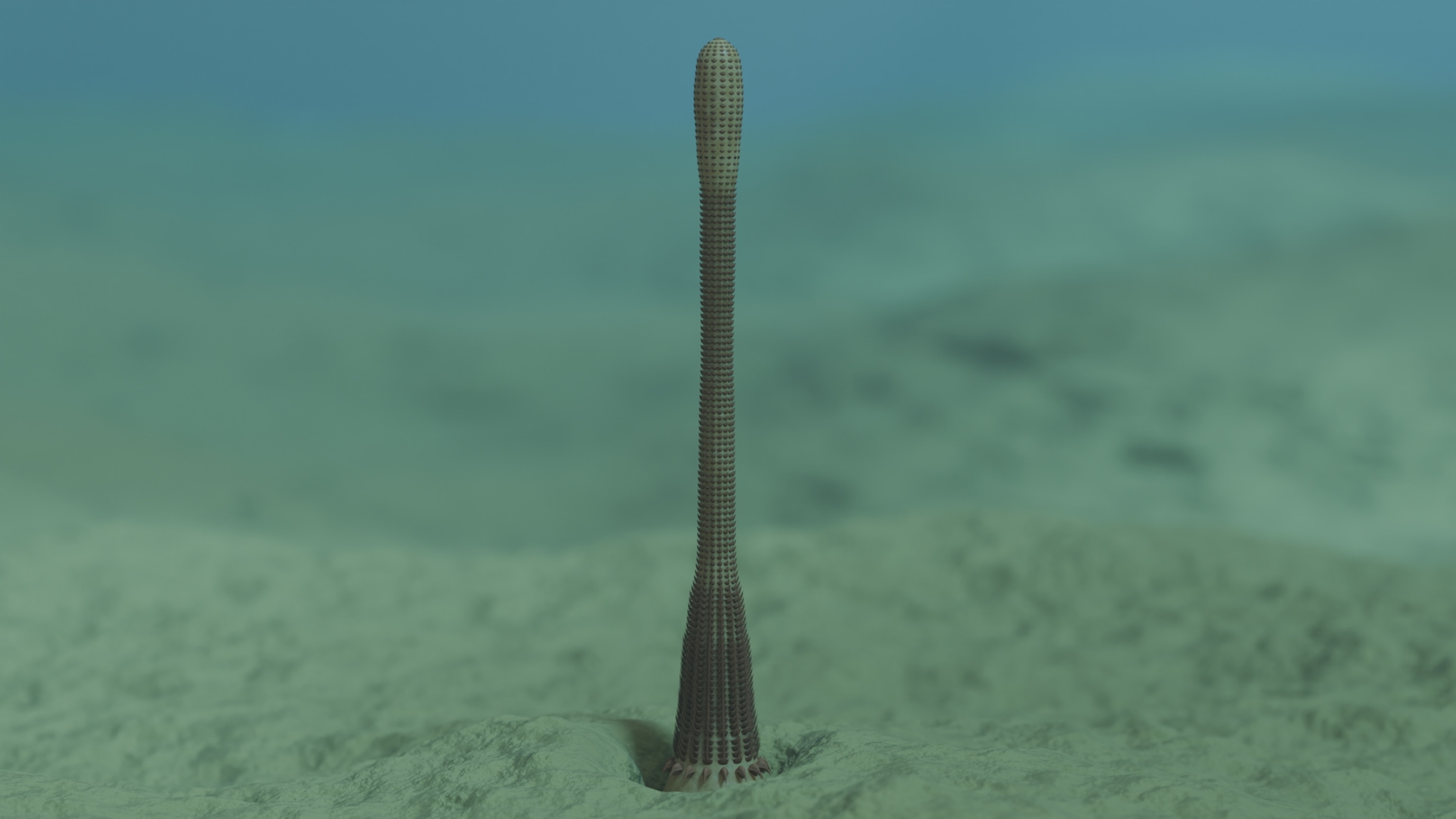

The creature was a priapulid worm, often known—for obvious reasons—as a “penis worm.”

“They’re … peculiarly shaped,” says Mussini.

Following the suggestion of a Star Wars-obsessed colleague, Mussini named the newly discovered Grand Canyon worm Kraytdraco spectatus after the “krayt dragon,” an enormous burrowing dragon seen in the streaming show The Mandalorian. An adult K. spectatus would have measured roughly six to eight inches long, says Mussini.

From within its body emerged a darting, retractable throat, reminiscent of the xenomorph in Alien. This throat, or pharynx, was ringed with spirals of teeth. The Grand Canyon worm differed from most of its fellows, however. While it had the usual spiky teeth around the ring of its extendable throat, the inside was filled with concentric rows of feathery-looking teeth, of a sort “that have never been observed anywhere else,” Mussini says.

The priapulid's pharynx

Named for Priapus, the Roman god of fertility, priapulids are far, far older than the vertebrate genitalia they resemble. Trace fossils and body remains from before the dawn of the Cambrian period suggest that they were some of the world’s earliest dedicated predators and ecosystem-engineering burrowers, devouring anything they could swallow. Some lived like hermit crabs in animal shells. Others hosted symbiotic accumulations of smaller worms.

“Everywhere we look in these exceptional preservation deposits, like China and the Burgess Shale, we see priapulids,” says Mussini.

In a video his team made reconstructing this new species of priapulid, the animal’s pharynx rises toward the camera as if chasing after prey, showing off the concentric rows of feathery teeth inside. While the bigger, heavy-duty teeth around the rim could scrape the sediment or bits of animal carcass, the more delicate rings may have filtered “for the finer particles the animal is really interested in,” Mussini says.

Once satisfied, “the pharynx itself can be folded inside out like the finger of a glove,” returning the worm to a more bulbous appearance.

Although it might be named for a Star Wars character, Mussini says the penis worm more closely resembled the sandworms seen in Dune with its sphincter mouth full of fine, sand-sifting teeth. Unfortunately for the research team, the name “Shai-Hulud” was already taken by an unrelated worm fossil.

“A priapulid would have been better to get that name,” says Mussini, “because the resemblance is quite uncanny.”

Priapulid worms are still around today, Mussini adds. About 20 living species survive, though they've been shrunken by time, now measuring mere millimeters long.

“There may have been some trend toward miniaturization as the eons went by,” he says of the priapulid worms that have endured half a billion years of evolution.

In other words, for penis worms, size wasn’t necessarily everything.