For billions of years, DNA has served as life’s information molecule, containing instructions for how and when to build the proteins of living organisms. But how long can that biological information survive? In a provocative new study, an international team of researchers reveals dinosaur fossils that are so well preserved, some contain the outlines of cells—and structures that might have formed from the dinosaurs’ original DNA.

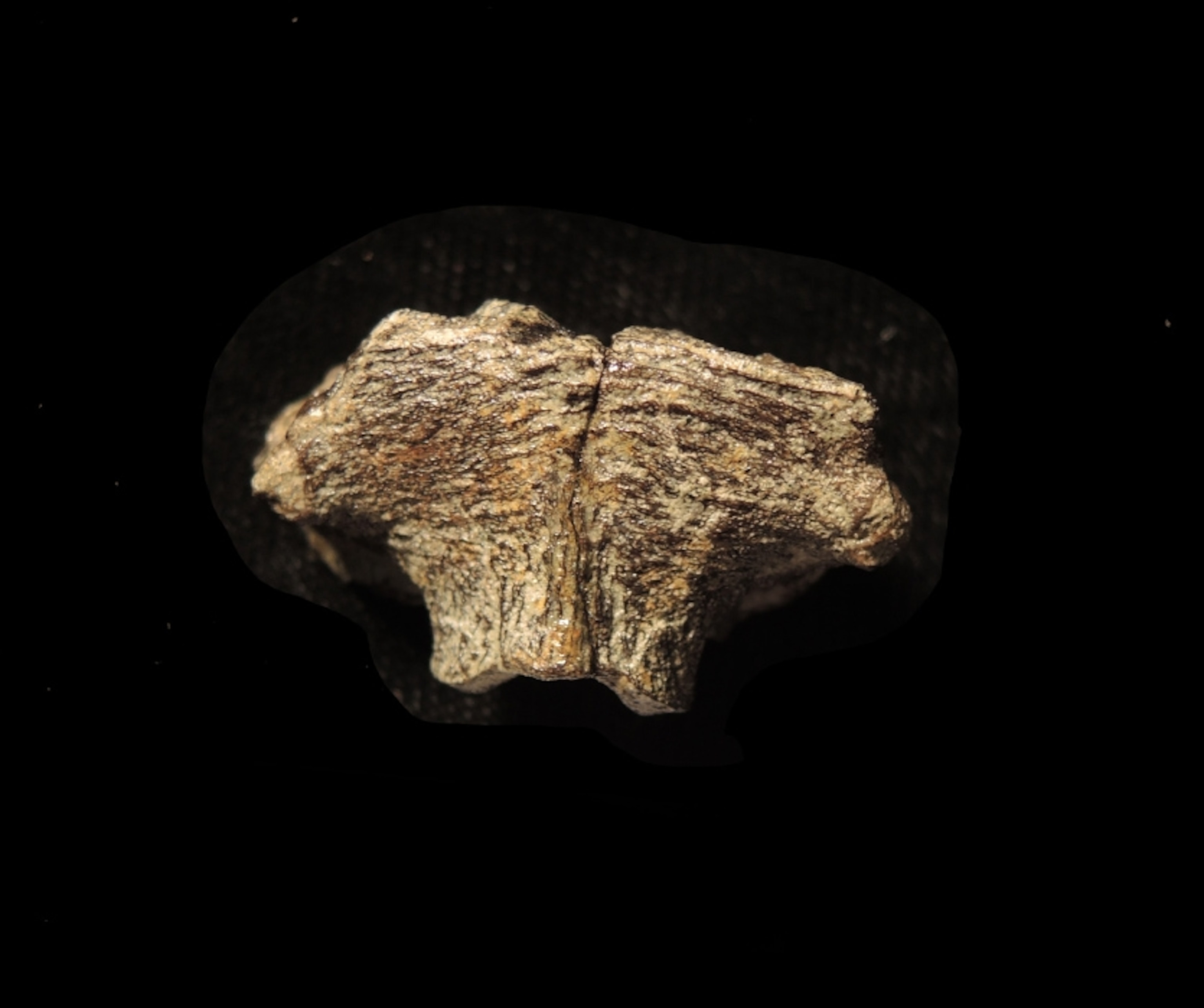

The study, published last week in National Science Review, takes a close look at two juvenile skull bones from the hadrosaur Hypacrosaurus stebingeri, a plant-eating dinosaur that lived in what’s now Montana about 75 million years ago.

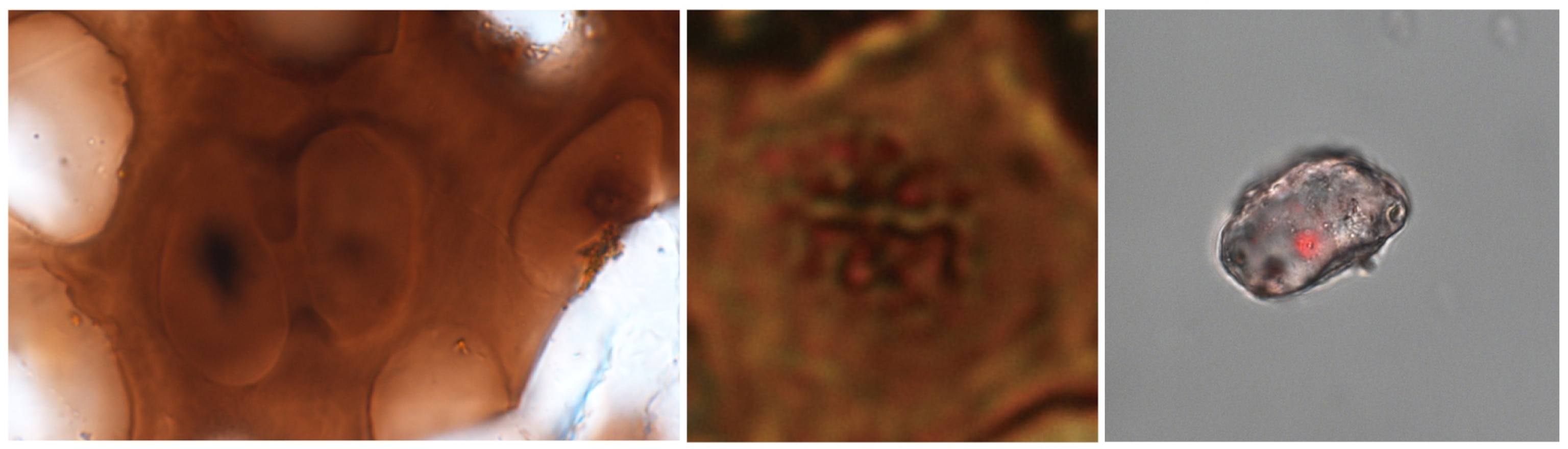

Inside the tiny fossils, researchers can see what appear to be cells, some frozen in the process of dividing. Others contain darkened balls that look just like nuclei, the cellular structures that store DNA. And one cell even seems to contain dark, tangled coils that resemble chromosomes, the condensed strands of proteins and DNA that form during cell division.

“It’s a sub-cellular level of preservation that’s never been reported before in a vertebrate,” says Alida Bailleul, a postdoctoral researcher at China’s Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology and lead author of the new study.

To test the fossilized material, the researchers applied stains that bind to DNA in living cells to the bits of dinosaur skull. These stains stuck to particular spots within the fossil cells, making them glow in fluorescent red and blue. As far as the researchers can tell, whatever the stains are binding to derived from the dinosaur’s original molecules, not an outside contaminant such as bacteria.

Does the discovery mean we can sequence dino DNA? Not even close. The researchers haven’t tried extracting DNA from the fossil cells, so they haven’t confirmed whether the material is unaltered DNA or some kind of fossil byproduct of genetic material breaking down. Scientists also caution that if DNA is present within the dinosaur cells, it’s probably in tiny fragments, chemically altered, and tangled up with what was once protein.

“We’re not doing the Jurassic Park thing,” Bailleul says.

Even so, the study serves as a reminder that fossils can preserve microscopic structures and even traces of the molecules that made up an organism’s cells, from pigments to proteins and more. One recent study even found biomolecules in a fossil of Dickinsonia, a creature that lived over half a billion years ago, and used them to confirm that the organism was an animal rather than another form of life.

“This research is still very much in its infancy, but the possibilities are absolutely thrilling if we suspend our disbelief, dig into the data, and continue to test and refine our ideas about molecular preservation in fossils,” says David Evans, a paleontologist at the Royal Ontario Museum who wasn’t involved with the study.

Shocking cells

The chance discovery of fossilized dinosaur cells began in the Montana badlands in the 1980s, when Chapman University paleontologist Jack Horner, then at Montana’s Museum of the Rockies, discovered a site that contained the bones of several nestling Hypacrosaurus stebingeri. Horner studied the juveniles’ limb bones, but he also found some Hypacrosaurus skulls among the remains. To see the skulls’ inner structure, Horner and his colleagues embedded some of them in resin and then ground them down into sections slightly thicker than strands of hair.

The slides with these little bits of dinosaur skull sat in obscurity for over two decades at the Museum of the Rockies until Bailleul—then a Ph.D. student at the museum—pulled them out in 2010 to study the small joints and sutures that hold the skulls together. As she looked at the thin sections under her microscope, Bailleul noticed little circular configurations in one nestling’s supraoccipital bone, which formed part of the back of the skull.

The circular structures looked like cells, and Bailleul noticed that many of them had smaller, darker spots within them, resembling nuclei. Some even contained tangled coils that reminded Bailleul of chromosomes.

“I freaked out a little bit—moving away from the microscope, thinking, moving back to the microscope,” she says. “I was like, Oh my god, that can’t be, there’s nothing else they can be!”

Bailleul was so stunned by what she had seen that she kept it to herself for a couple days—but one of Horner’s former Ph.D. students, North Carolina State University paleontologist Mary Schweitzer, happened to be visiting the museum. Schweitzer, a pioneer in molecular paleontology, had previously published evidence that dinosaur fossils could preserve cells and—controversially—even traces of their original proteins.

Schweitzer looked at the fossils and agreed that Bailleul had found something extraordinary. For the next decade, Bailleul worked with Horner, Schweitzer, and their colleagues to study the fossils, treating the endeavor as a long-term side project. In 2014, the team got an unexpected confidence boost when a Swedish group announced that it had found a 180-million-year-old fern with fossilized nuclei and chromosomes. “When that fern paper came out, I was like, Wow, okay, we’re not crazy,” Bailleul says.

After studying the cellular structures, the team wanted to get a better sense of what the fossils’ were made of. Bailleul visited Schweitzer’s lab in Raleigh, North Carolina, and brought the samples for testing, double-checking their work with fresh emu tissue samples (in a different lab, to avoid contamination).

First, the researchers applied chemical stains to the fossils that bind to cartilage, which suggested that the developing bits of dinosaur skull had not yet hardened into bone when the animals died, as the team suspected. Bailleul and Schweitzer then isolated some of the fossil cells and applied propidium iodide and DAPI, two chemical stains widely used in medical research to visualize fresh DNA. Unsurprisingly, the emu cells better attracted the stains—but the stains also glommed on to specific points within the fossilized dinosaur cells.

“I’m not even wiling to call it DNA because I’m cautious, and I don’t want to overstate the results,” Schweitzer says. “There is something in these cells that is chemically consistent with and responds like DNA.”

How does DNA fossilize?

If intact DNA is present in these dinosaur fossils, scientists may need to reappraise the molecule’s ruggedness. Past studies have found that genetic material disintegrates in bones after a few million years. The oldest complete genome ever sequenced comes from a 700,000-year-old horse bone found in Siberia, frozen in the permafrost since the animal’s death—and the Hypacrosaurus bones are about a hundred times older.

Bones are highly porous in life, which makes them imperfect time capsules in death. The preserved dinosaur cells were probably embedded in cartilage, Schweitzer says, which lacks pores. The structure of cartilage may have protected the cells inside—and their chemical constituents—more effectively.

“Fossilized, calcified cartilage may be an ideal place to search for exceptionally preserved biomolecules in other fossils, as this tissue may be less prone to contamination and internal decay than bone,” Evans says. “In calcified cartilage, the cells become trapped and isolated in their matrix and are more likely to be preserved in a sealed micro-environment.”

Despite cartilage’s protection, the chemical stains might not be binding to unaltered DNA in the fossils. Bailleul and Schweitzer say that if DNA is present, it may have survived because of the formation of extra chemical bonds within different parts of a single DNA strand. In living creatures, these sorts of reactions—called crosslinking—are so toxic, some anticancer drugs induce these bonds in tumor DNA. But during fossilization, the bonds might help stabilize DNA for the long haul.

Jasmina Wiemann, a Yale Ph.D. student who specializes in how biomolecules fossilize, says that crosslinking between DNA and proteins could also help with fossilization. Past studies have shown that DNA and histones—proteins that act as spools for genetic material—can bind to each other. She adds that more chemical analysis would be needed to confirm the idea.

If the dinosaur cells preserve unaltered DNA—which is a major if—the chemical stains tell us that the DNA strands contain at least six base pairs, the individual “rungs” of DNA’s ladder-like structure. While the stains provide only a minimum length, fragments that short probably wouldn’t be useful for sequencing DNA. Beth Shapiro, a paleogenomicist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, says that ancient-DNA researchers ignore fragments shorter than 30 base pairs, since pieces of genetic material that tiny don’t contain enough information to be accurately placed within a genome. Slotting DNA fragments that small into a full genome would be like trying to find a specific sentence in Moby Dick while knowing only that it contains the word “whale.”

But fossil DNA that can’t be sequenced could still be useful. Wiemann and others have shown that even highly altered fossil proteins can preserve valuable information, such as an animal’s metabolic rate, and the same could be true for the remnants of DNA.

More chemical analysis is needed to pin down precisely what’s contained in these bits of dino skull, but Bailleul hopes that in the future, scientists will fully understand how DNA can fossilize—and what genetic information those preserved bits might contain.

“We would be crazy scientists if we left it there and did nothing,” Bailleul says. “I know that it’s preliminary work, but if no one starts with something, then it’s never going to go anywhere.”