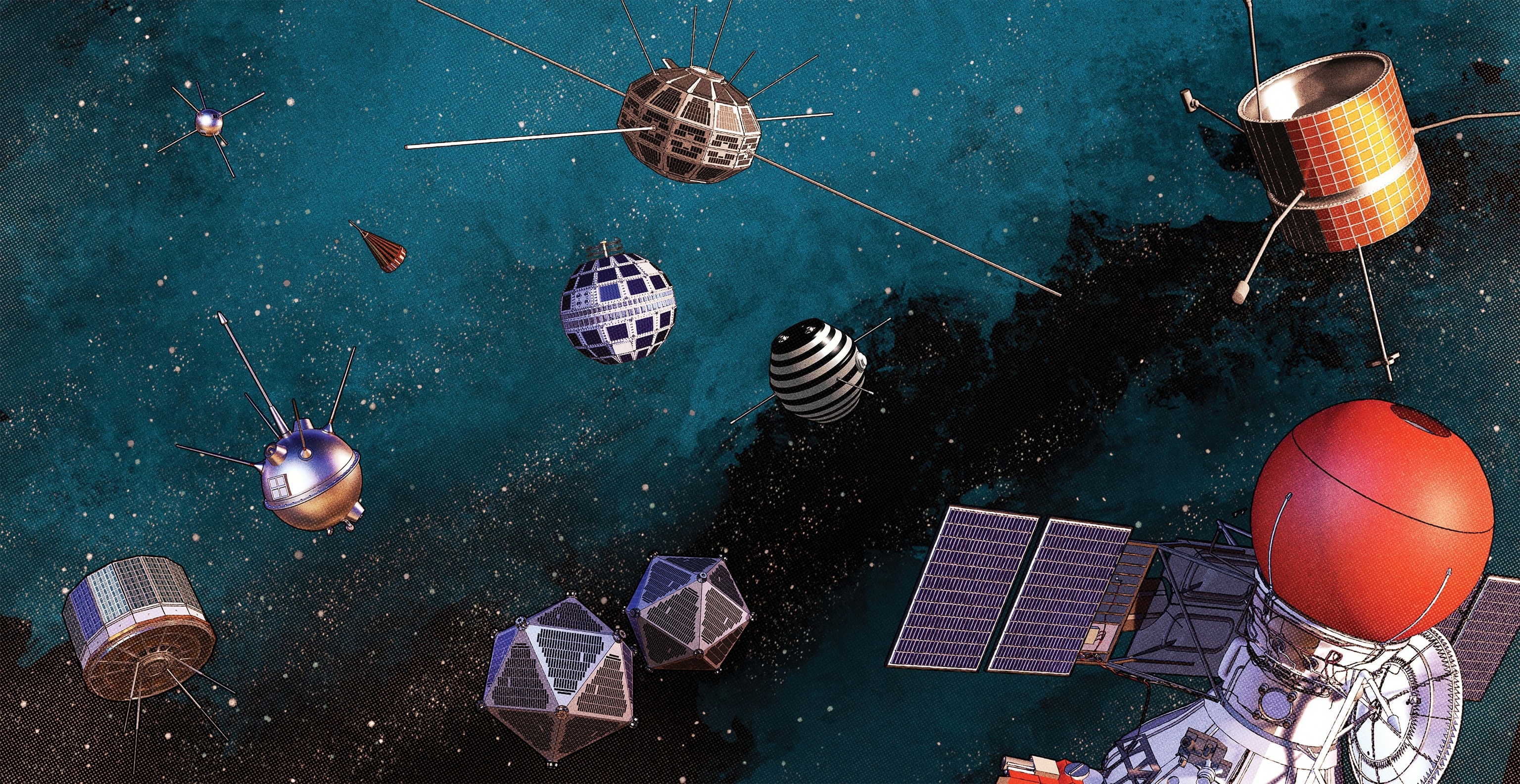

In one view, Vanguard 1 is a quintessential piece of space junk: an antennaed aluminum ball that Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev dismissively compared to a grapefruit. The United States launched it in March 1958, and the satellite returned radio signals until May 1964. Defunct ever since, it’s the oldest human-made object in orbit.

But to space historian Matt Bille, that grapefruit is “one of the most precious objects” of the early space age, deserving of a place in the Smithsonian. And scientists, he says, could glean much from it about long-term exposure to space. Bille, along with a few like-minded engineers and historians, made this case at a recent conference of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, where Bille is an associate fellow, presenting detailed plans for a hypothetical mission to deorbit Vanguard 1 and bring it home. Though expensive and challenging, they argued, such a mission is feasible—and might appeal to a robotics company or an agency looking to showcase its grappling tech.

(How the space race launched an era of exploration beyond Earth.)

The idea has turned heads, not least for challenging a preference for in situ preservation that’s increasingly enshrined in heritage fields, including the burgeoning discipline of space archaeology. Old satellites “need to be left where they are,” says Alice Gorman, who sits on the International Council on Monuments and Sites’ aerospace committee. They’re safer in orbit, she says, where they belong to no one nation and can be studied via photography and other remote sensing methods.

But space is getting crowded, Bille notes—more than 14,000 satellites orbit the Earth, to say nothing of debris. He and his co-authors frame their technical paper as a thought experiment: Should we ever consider nabbing historically significant satellites? Which might merit consideration? They offer 11 more candidates, each a national first or a pioneering mission, and all conceivably retrievable, Bille says, if one dreams big.

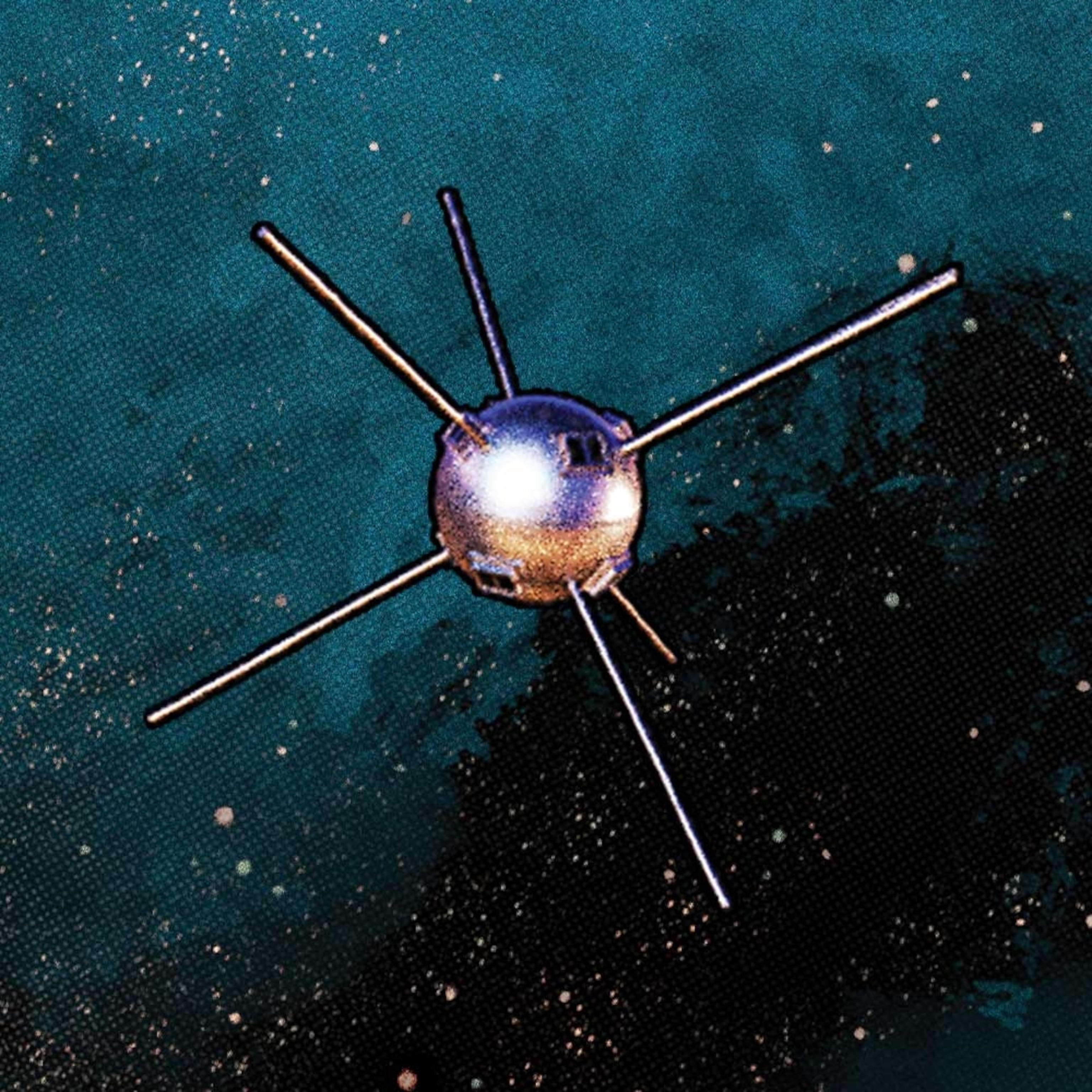

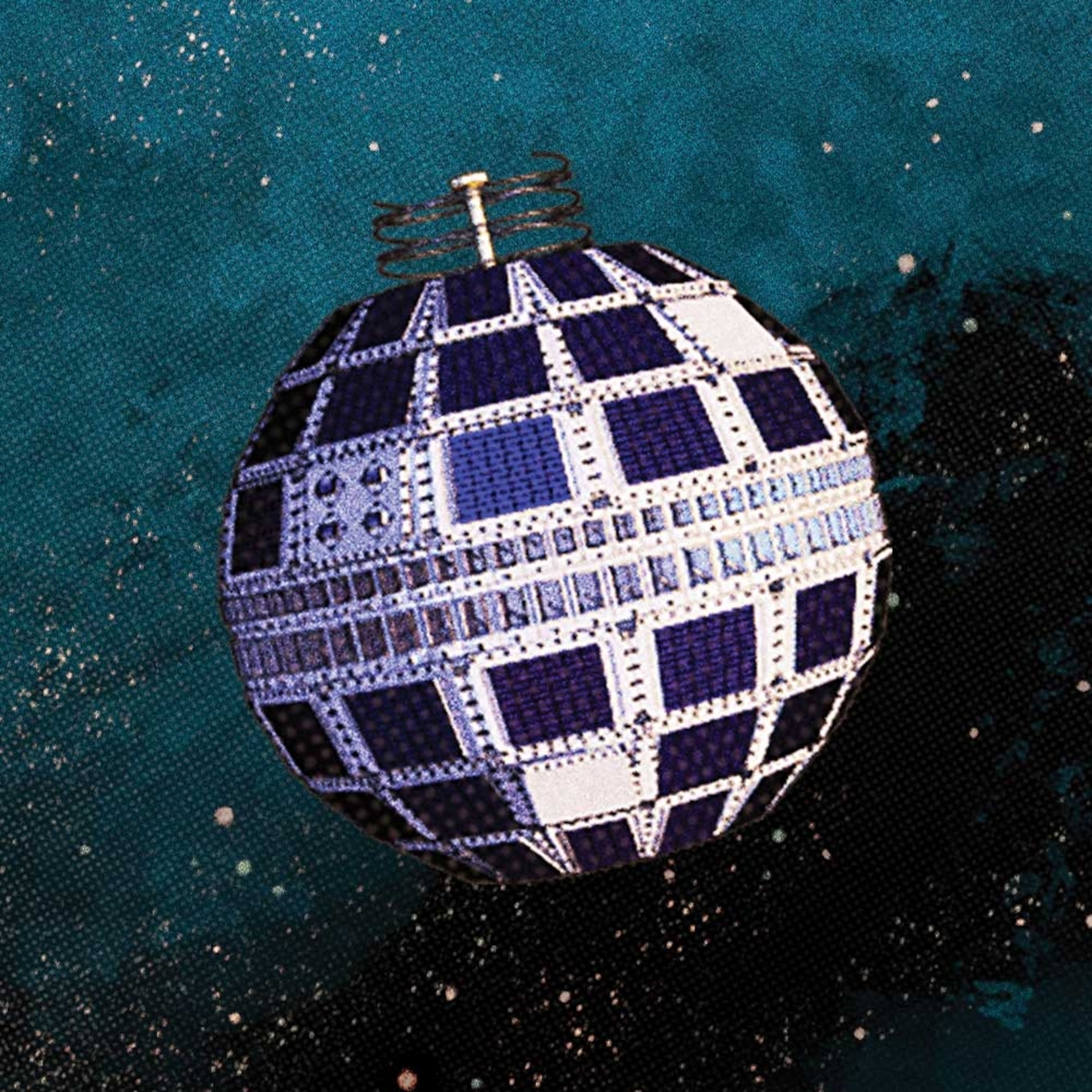

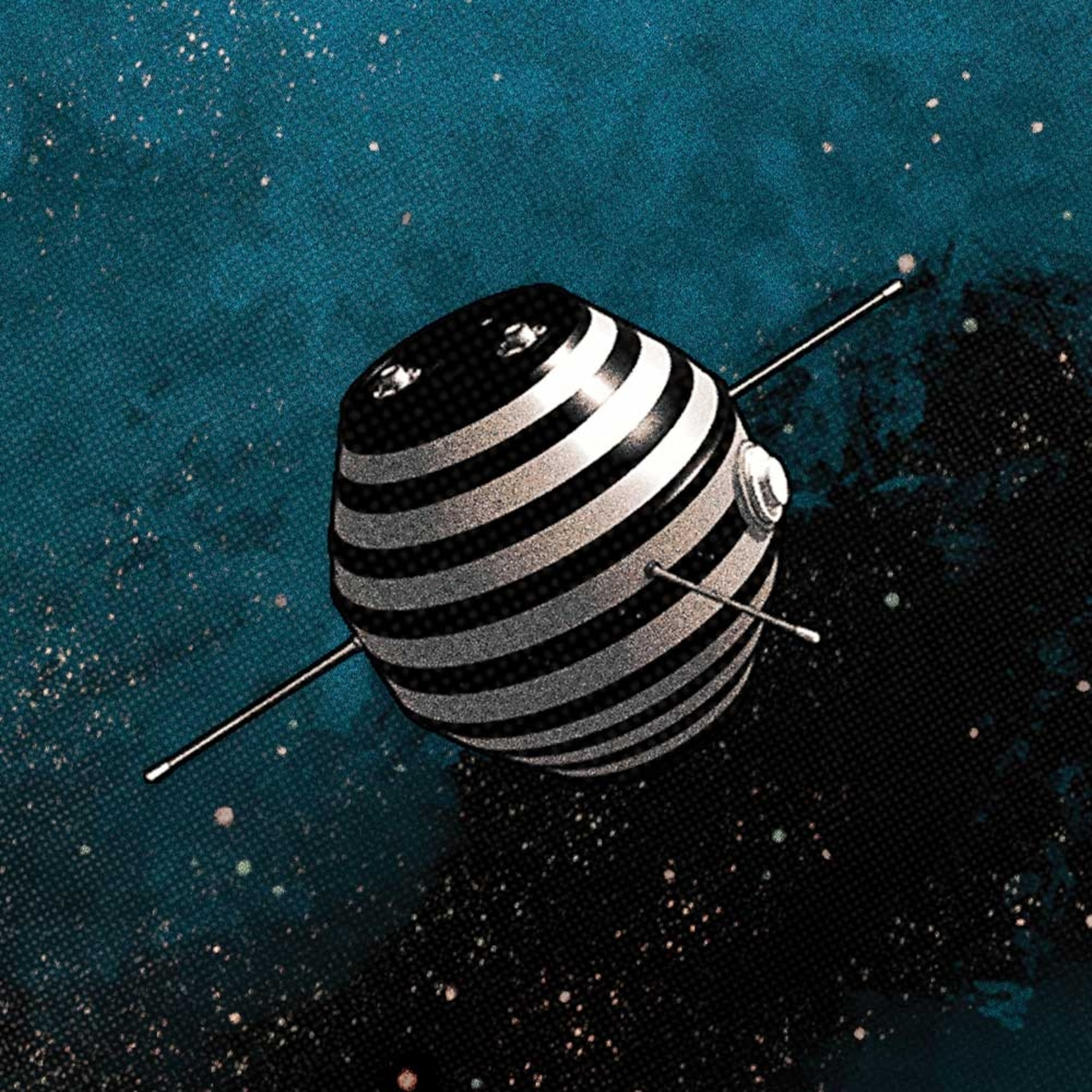

Vanguard 1

U.S. • Launched on March 17, 1958 • Low Earth orbit

The second U.S. satellite in orbit (the first, Explorer 1, burned up upon reentry in 1970), its most distinguished contribution was to confirm, via variations in its orbit, that Earth was less round than supposed, bulging around the Equator.

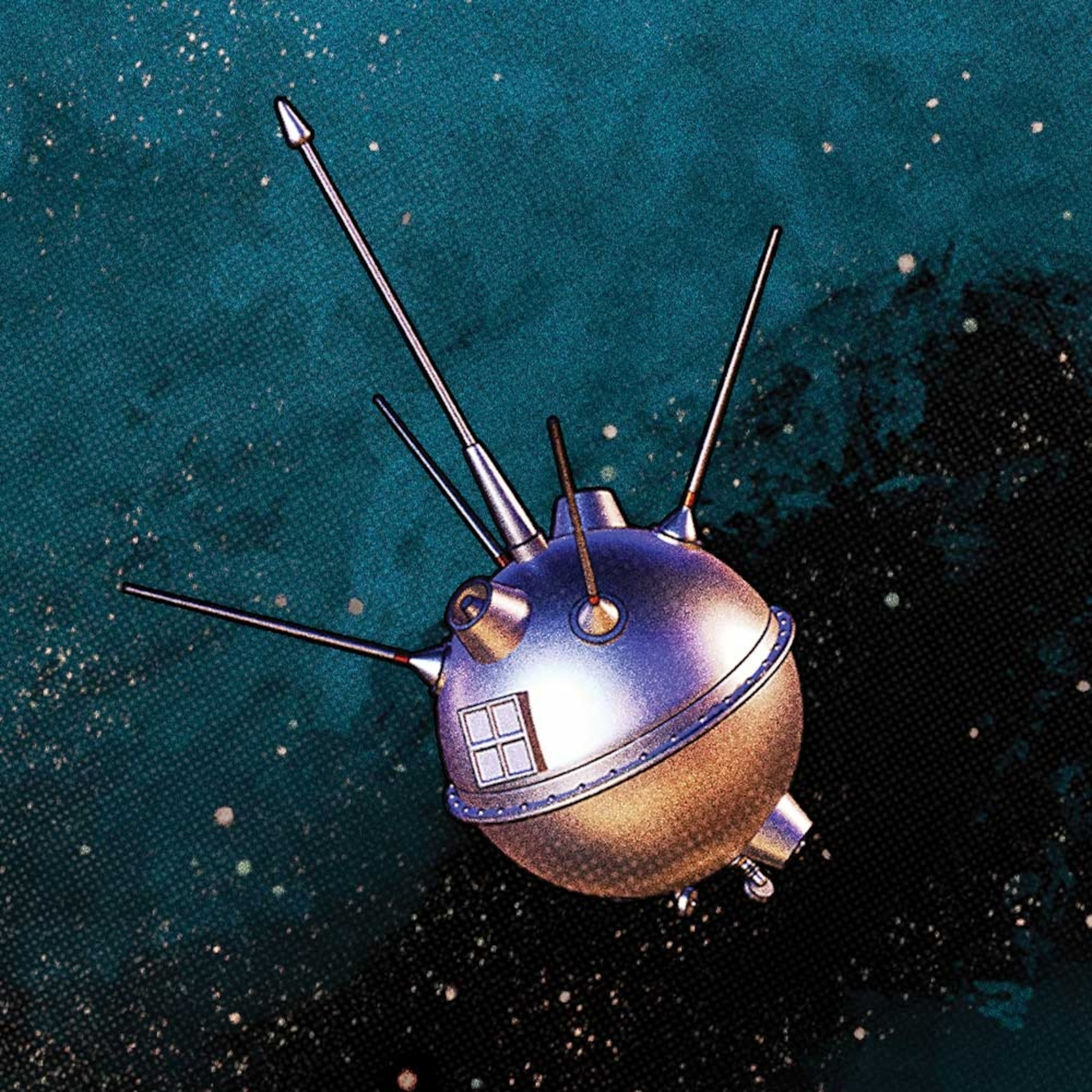

Luna 1

U.S.S.R. • January 2, 1959 • Solar orbit

A yoga ball to Vanguard 1’s grapefruit and the first spacecraft to escape Earth’s gravity. The Soviets aimed for the moon and missed by some 3,700 miles. Luna 1 became, instead, the first spacecraft to settle into orbit around the sun.

Pioneer 4

U.S. • March 3, 1959 • Solar orbit

Like Luna 1, the first American craft to travel beyond Earth’s orbit also blew its objective, passing too far from the moon to photograph it as planned. It returned good data, though, on the Earth’s

encircling radiation belts.

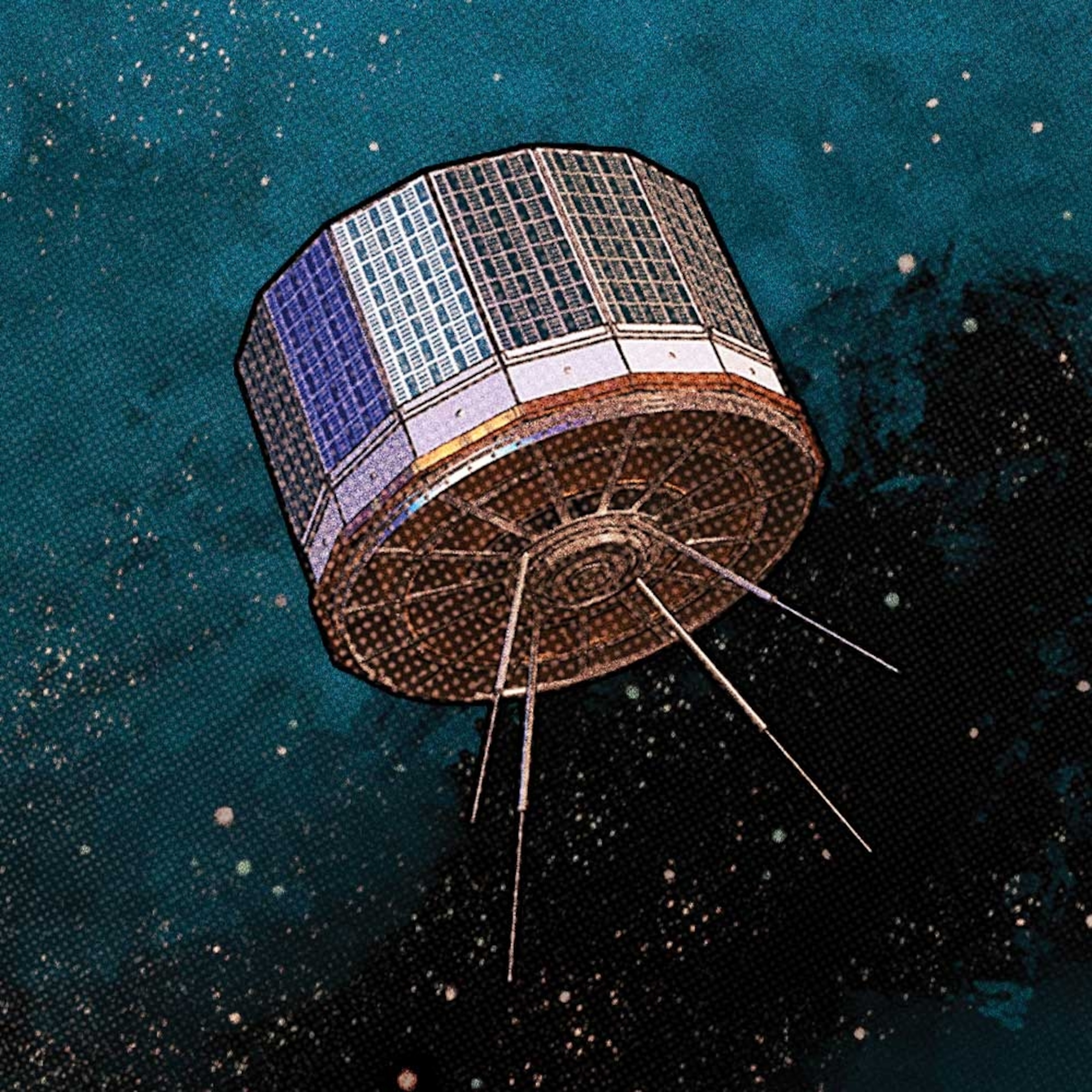

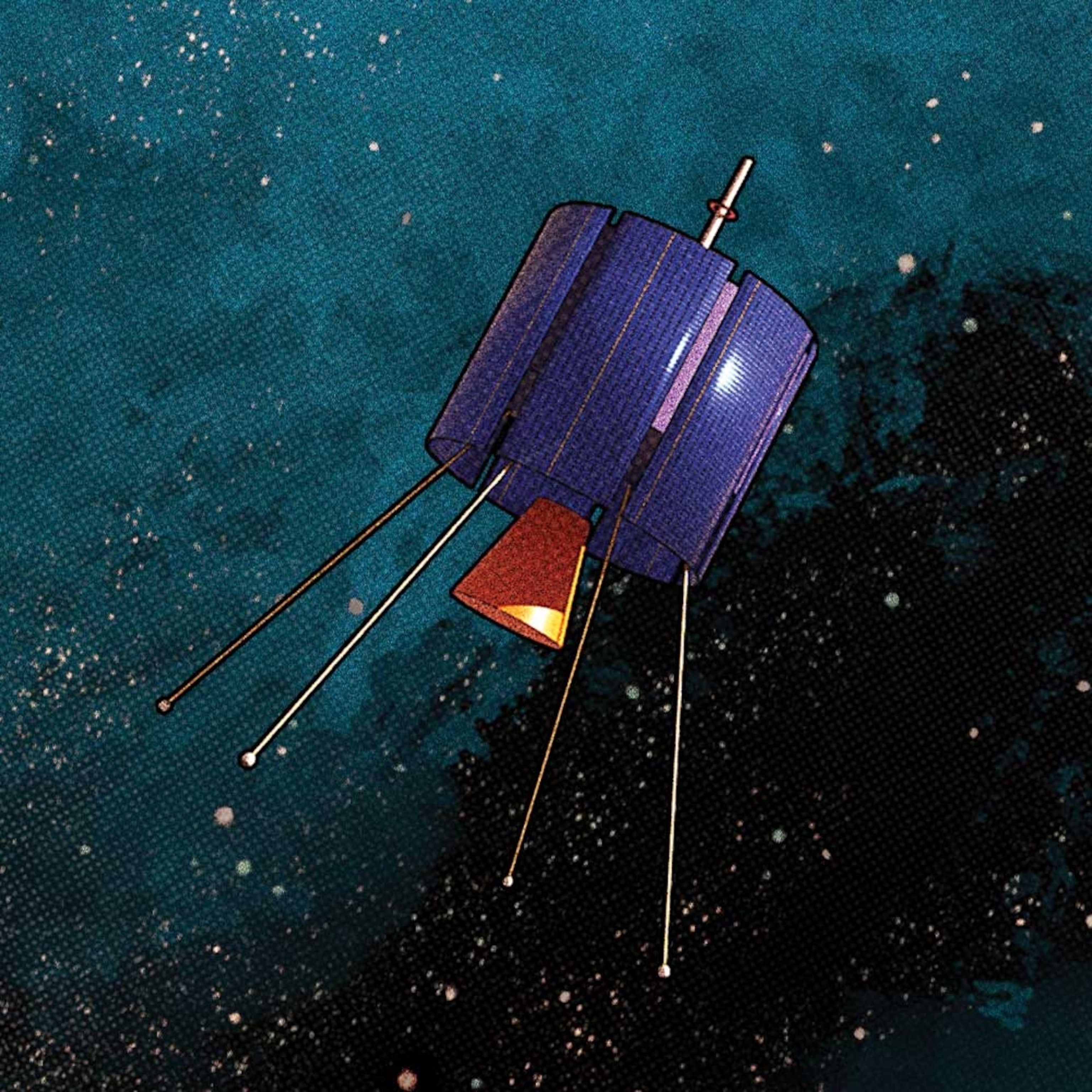

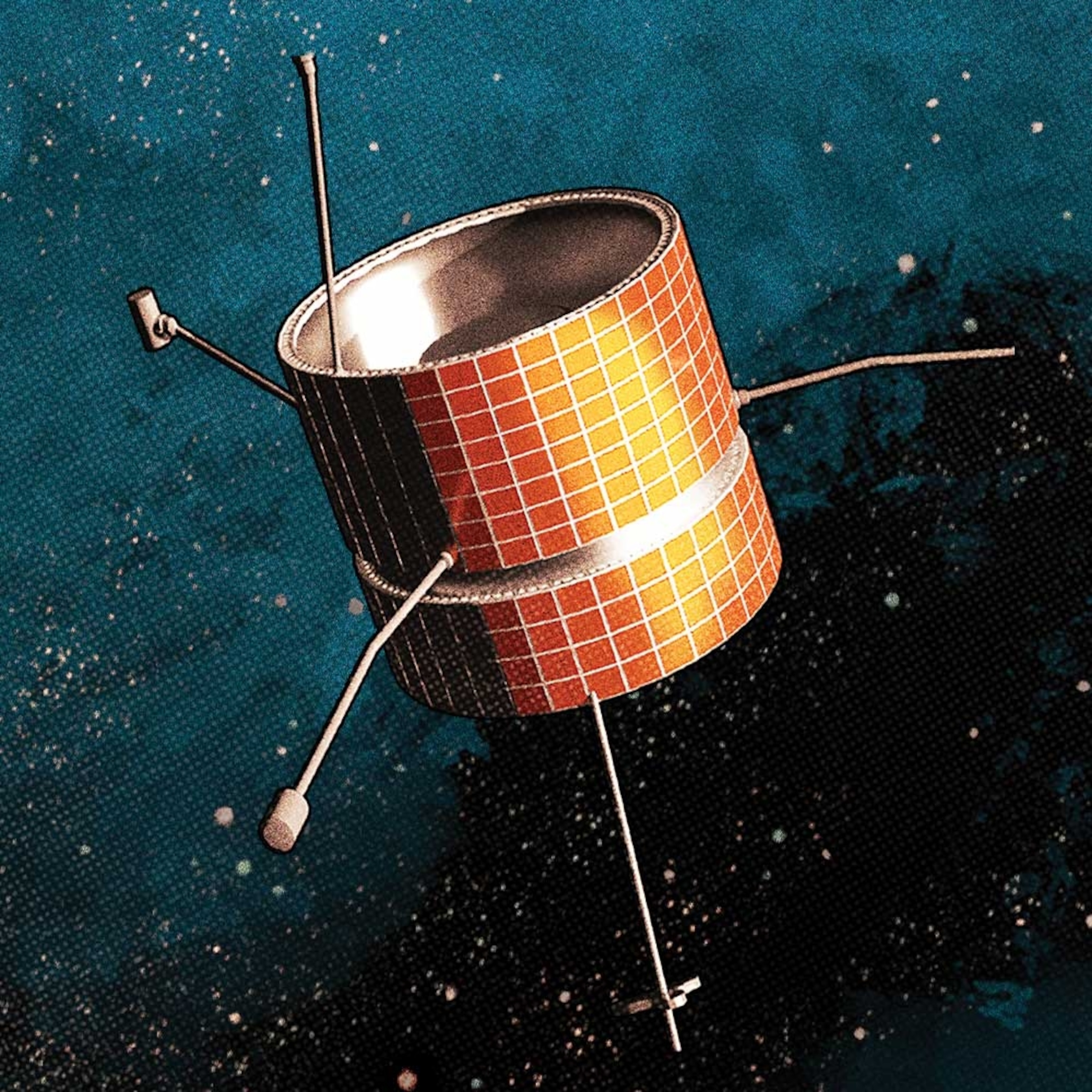

Tiros 1

U.S. • April 1, 1960 • Low Earth orbit

Today we take weather-observation satellites for granted, but when NASA sent up its first attempt at one—“a flying ladies’ hatbox,” as

one newsreel called TIROS 1—just how useful it would be for forecasting was still an open question.

Telstar

U.S. • July 10, 1962 • Low Earth orbit

The first ever active communications satellite sporadically relayed TV images across the Atlantic until, as space historian Bille puts it, “we sort of killed it by accident.” Radiation from

a high-altitude nuclear test knocked it out after seven months.

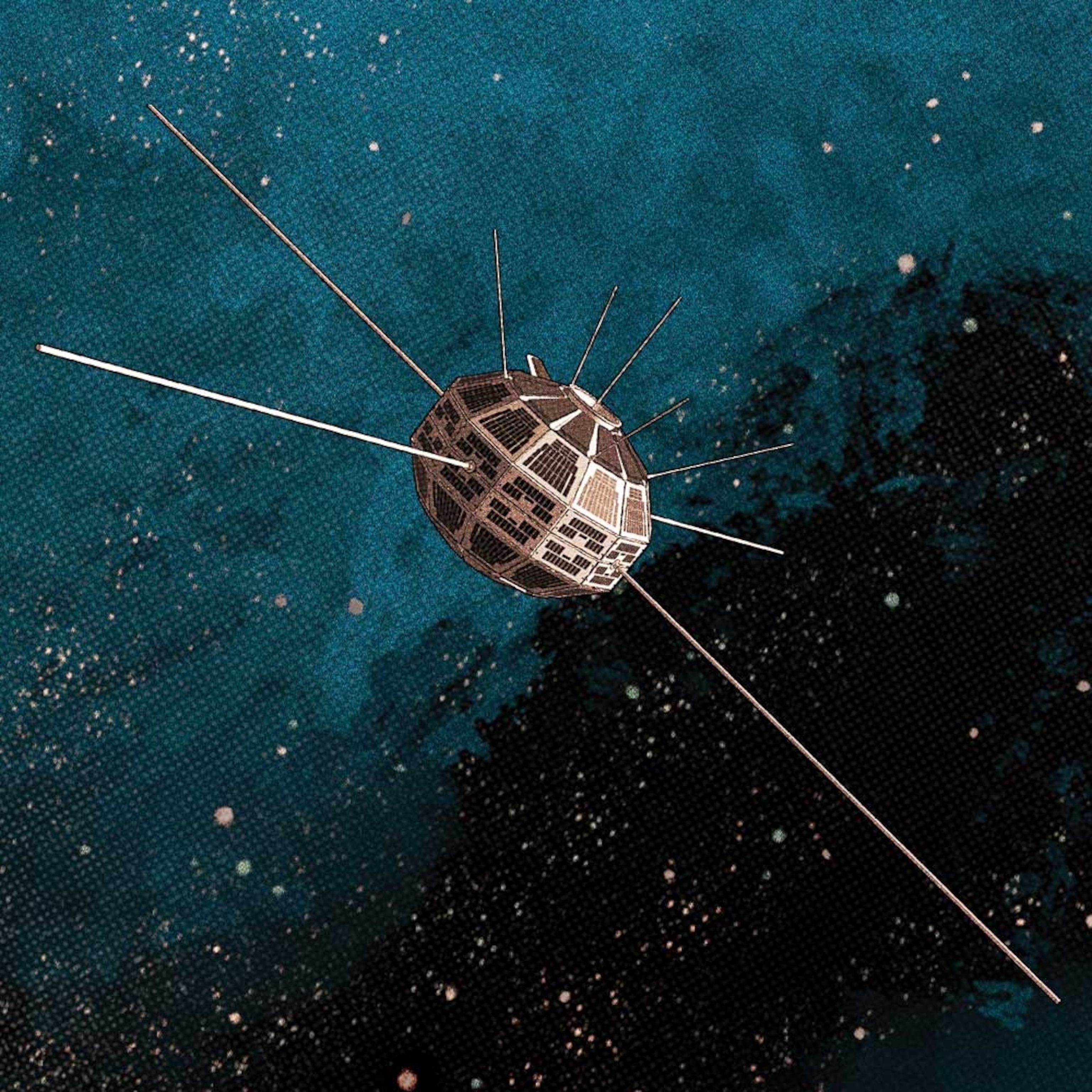

Alouette 1

Canada • September 29, 1962 • Low Earth orbit

Canada became the third nation in space with this workhorse, which sent back some two million data snapshots of the ionosphere—the atmospheric layer that reflects radio waves—during a record-setting 10 years in operation.

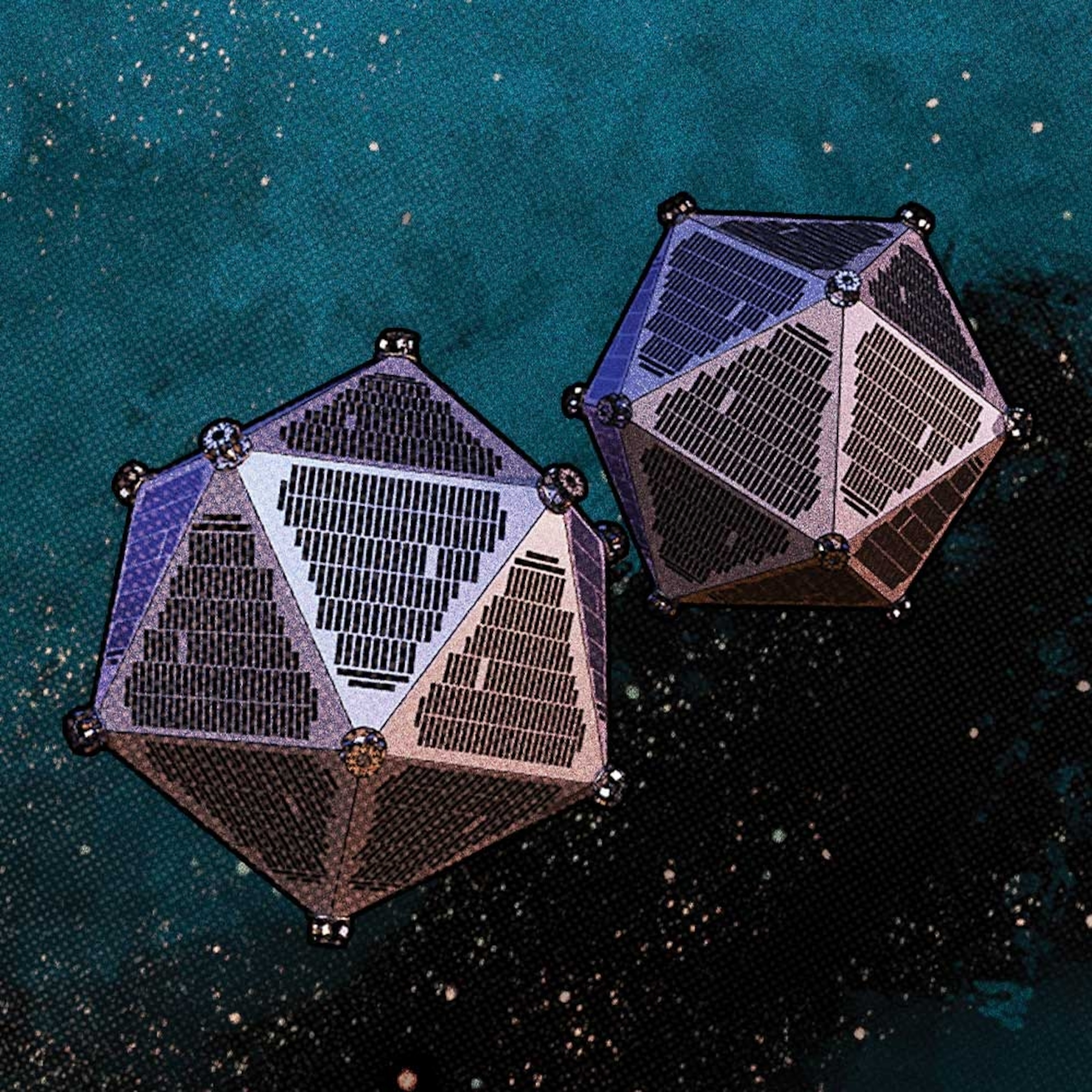

Vela 1A & B

U.S. • October 17, 1963 • High Earth orbit

From the Spanish velar: to watch. This pair of polyhedrons went up weeks after the U.S. ratified the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, designed to detect nuclear explosions and work together to triangulate their location.

Early Bird

U.S. • April 6, 1965 • Geostationary orbit

It was the first commercial communications satellite in a stationary orbit, and staying put over its coverage area permitted uninterrupted transmission. Cable TV viewers in the 1980s or ’90s can thank geostationary satellites that followed Early Bird’s lead.

Astérix

France • November 26, 1965 • Low Earth orbit

France’s first foray into orbit—and the first satellite named for

a comic-book character, a pint-size Gaulish warrior—was damaged upon ejection from its rocket and transmitted no or next to no data.

Pioneer 6

U.S. • December 16, 1965 • Solar orbit

“We were gearing up to go to the moon,” Bille says, “and we wanted some idea of what conditions were like in interplanetary space.” The first probe to study things like solar wind and the interplanetary magnetic field, it fed data to NASA into the ’90s.

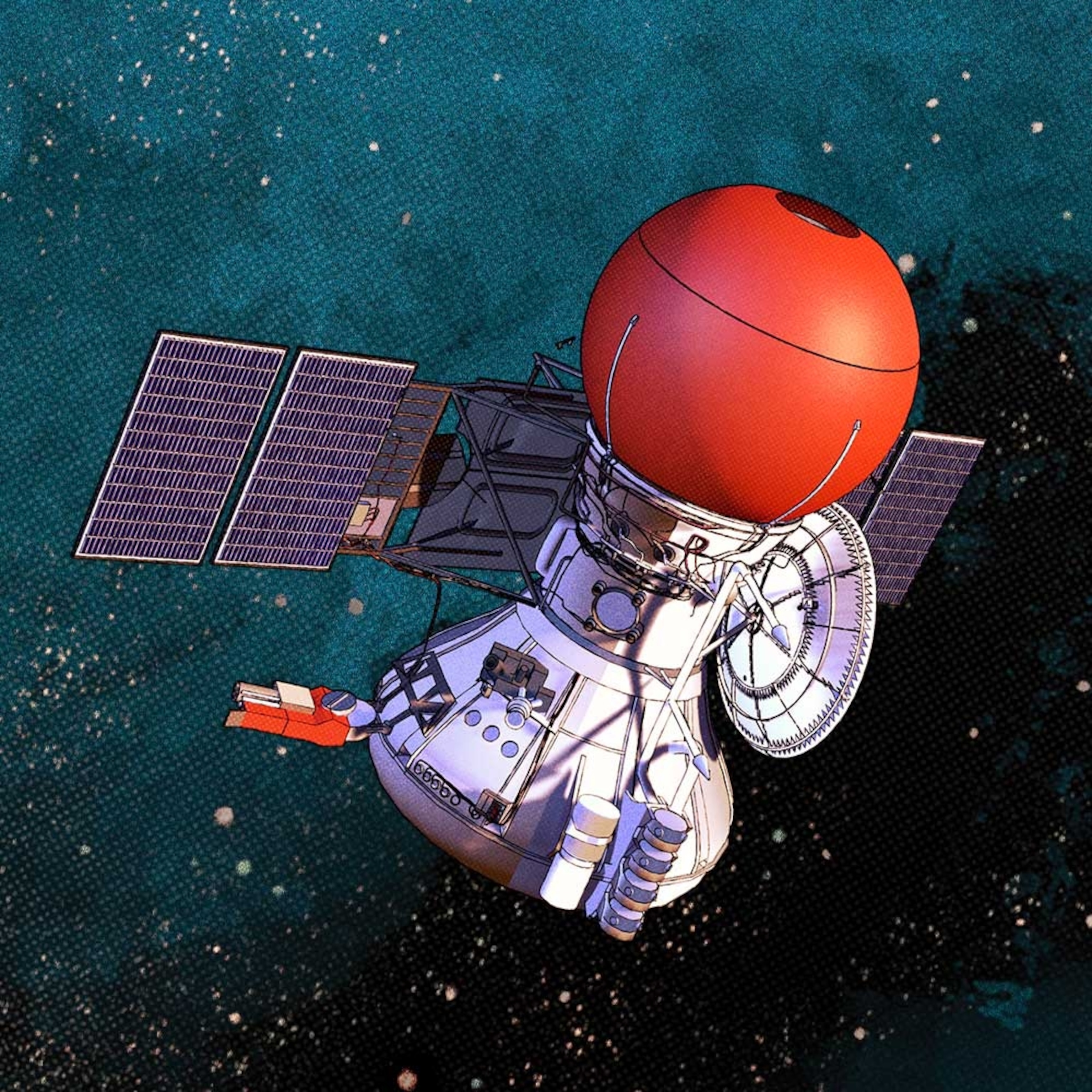

Vega

U.S.S.R. • December 15, 1984 • Solar orbit

Scientists cooperated across Cold War lines on a mission that sent this massive satellite on

a journey that included a Venus flyby and a pass through the gas cloud surrounding Halley’s comet.

A version of this story appears in the

October 2025 issue of

National Geographic magazine.