How elite athletes train their nerves for Olympic pressure

New research on heart rate variability suggests that composure isn’t a personality trait. It’s a physiological skill the nervous system can train—one that may determine who thrives when the stakes are highest.

Most Olympic races are decided by fractions of a second. Sometimes, they’re decided before an athlete even begins.

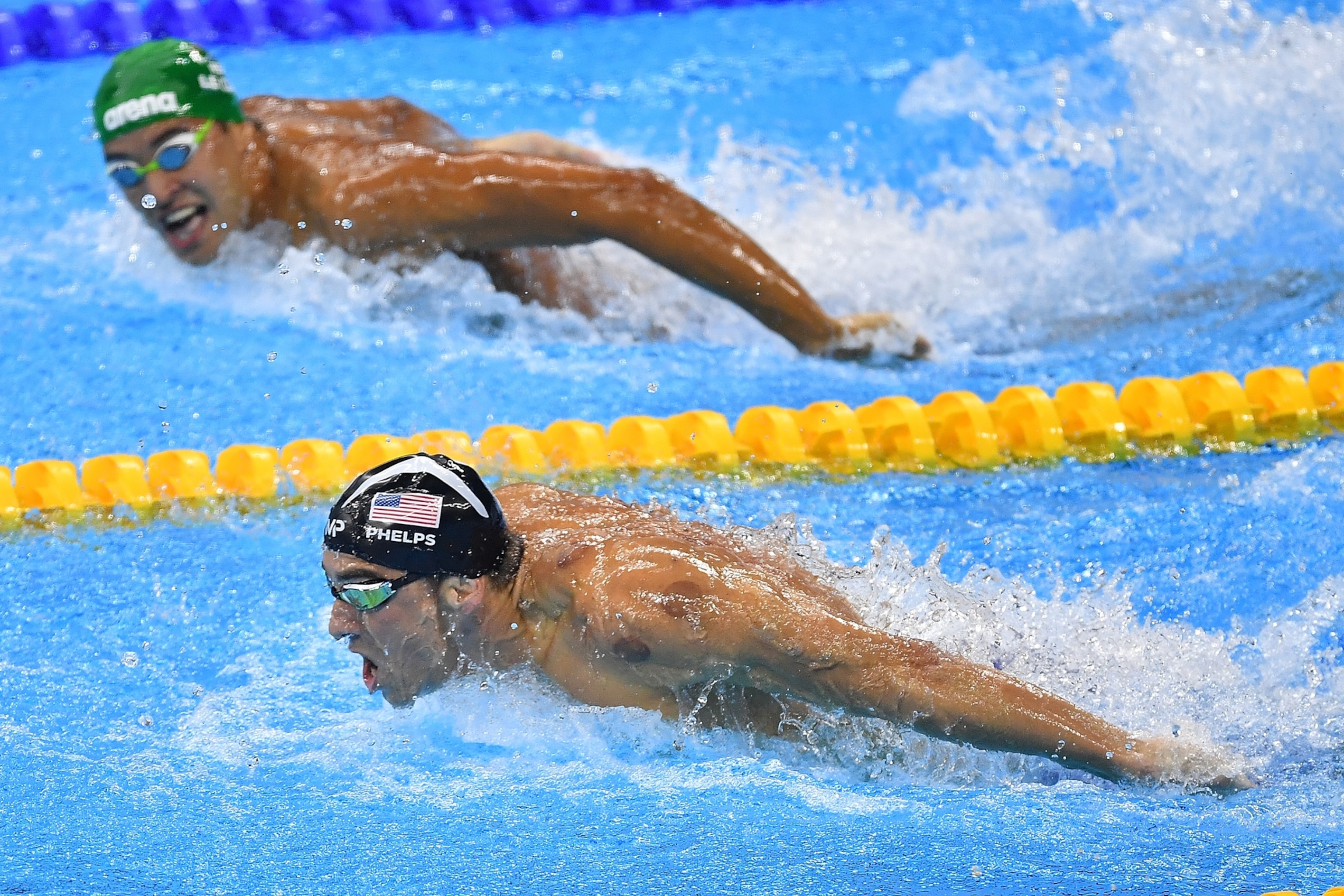

At the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro, just minutes before the 4x200-meter freestyle relay, Michael Phelps tore his swim cap on the pool deck. It was the kind of tiny malfunction that can bloom into a catastrophe at the highest level of sport. There were cameras, sponsors, and a stadium full of noise. Yet he reacted with the speed and ease of someone buttoning a shirt. He flipped a teammate’s cap inside out, pulled it on, and swam the anchor leg to gold.

The moment looked like instinct. It wasn’t. It was rehearsal—so deeply practiced that it had become physiological.

For years, Phelps had imagined every possible race. In quiet moments, he would “play the tape,” envisioning various versions of the same swim: the ideal execution, the sloppy one, the one where something went wrong. By the time it happened in Rio, the surprise was familiar.

“We did this thing called visualization,” he explains. “Swim the race three different ways in your head. If something does happen, you’ve already thought about it.”

That preparation helped build a physiological skill that scientists are only now learning how to measure.

The body’s ability to shift gears

For decades, moments like Phelps’ have been explained using language such as “mental toughness” or “clutch performance.” Researchers who study performance under pressure now see something more precise—and more measurable— at work.

Heart rate variability, or HRV, reflects how efficiently the body absorbs stress and returns to equilibrium. In high-stakes settings, that flexibility may matter as much as strength or endurance.

Measured over time, HRV serves as a noninvasive biomarker that helps researchers and coaches monitor adaptation, stress, and recovery. It doesn’t replace fitness metrics. But HRV does add context to what fitness does not capture well: whether the system is ready to handle stress today and whether it can return to baseline afterward.

Vikram Chib, a neuroscientist who studies motivated performance, focuses on how the brain integrates incentives with motor output. In laboratory tasks designed to simulate high stakes, his group has found that people who are highly sensitive to rewards are more likely to choke. Money, status, and the gaze of an audience all register as incentives. The brain encodes them into value signals that can interfere with smooth execution.

(‘Hysterical strength’? Fight or flight? This is how your body reacts to extreme stress.)

“People often think performance is just motor learning, learning repeated movements. But you never do those movements in isolation,” Chib says. “You’re performing while the brain is processing incentives, and that processing changes what the body does under pressure.”

In those moments, the nervous system can struggle to distinguish a championship final from genuine danger.

When that happens, that shift does not stay confined to decision‑making circuits. It’s associated with changes in breathing, muscle tension, and heart rhythm, shifting the balance of the autonomic nervous system, which can be measured through heart rate variability.

Crucially, this disruption does not stay confined to the brain. It shows up in the body.

A measure of flexibility

A healthy heart doesn’t tick like a metronome. It constantly adjusts, speeding up, slowing down, responding to stress, and then easing back toward calm. That rhythm reveals how adaptable the nervous system really is.

In athletes, higher resting HRV has been linked not just to aerobic fitness, but also to agility, coordination, and sleep quality. That matters because consistency under pressure relies on more than physical strength. It depends on a nervous system that isn’t already braced for threat.

(Can scientists ‘solve’ stress? They’re trying.)

Research suggests that intense effort can disrupt that regulation even when the body feels strong. A 2024 study found that exhaustive exercise led to sharp drops in several HRV measures linked to autonomic recovery. In practical terms, it helps explain why an athlete can feel physically capable while their nervous system is still struggling to regain balance. HRV does not offer a simple green or red light, but when tracked over time, it can provide a physiological cue for when to push and when to restore.

Closely related is interoception, the ability to sense internal signals such as heartbeat or breath. That awareness becomes critical when stress or fatigue pushes the body into unfamiliar territory. Many cognitive and behavioral strategies work, Chib suggests, not because they erase pressure, but because they steady this internal feedback loop, making it easier to notice rising tension and adjust before it takes over.

“Being able to sense what’s happening inside your body becomes critical under stress or fatigue,” Chib says.

Seen through this lens, composure stops looking like a personality trait. It’s physiological capacity.

Regulating the body first

That understanding helps shape the work of sports psychologists like Caroline Silby, who oversees mental performance and mental health services for U.S. Figure Skating. The first step, she says, is recognizing that stress response is not a verdict on performance.

“The mind automatically tries to protect us by searching the environment for anything we need protection from,” Silby says. “Even when people are performing really well, the mind still does this.”

One tool she uses with athletes is the “rule of opposites.” If anxiety speeds them up, they deliberately slow down. They might walk backward instead of pacing forward or exhale when they notice themselves holding their breath. Small tactile cues, such as gently tugging on the ears, tensing and releasing a nondominant fist, or tapping pressure points, pull attention toward neutral sensation.

Those interventions seem simple. But they reflect a broader scientific rethinking of what it means to perform under pressure.

Composure isn’t stoicism. It’s regulation— the ability to feel a surge of arousal and steer it.

One way to blunt the pressure encoded in the brain’s reward circuits is reframing. Instead of treating a single performance as a career‑defining verdict, athletes learn to see it as one moment among many. In Chib’s experiments, that shift improves performance under pressure by restoring a sense of scale and physiological balance.

Athletes who excel under pressure are not free of arousal. They are skilled at navigating it. Their nervous systems have learned that surprise is survivable, that discomfort is not danger, and that equilibrium can be practiced.