What This Unprecedented 13-Million-Person Family Tree Reveals

For starters, the new tree calls into question a prevailing theory for why people stopped marrying close relatives.

The information tucked away in the branching lines of family trees can help individuals answer questions about the movement of their ancestors around the world, their physical traits, and even their risk of disease.

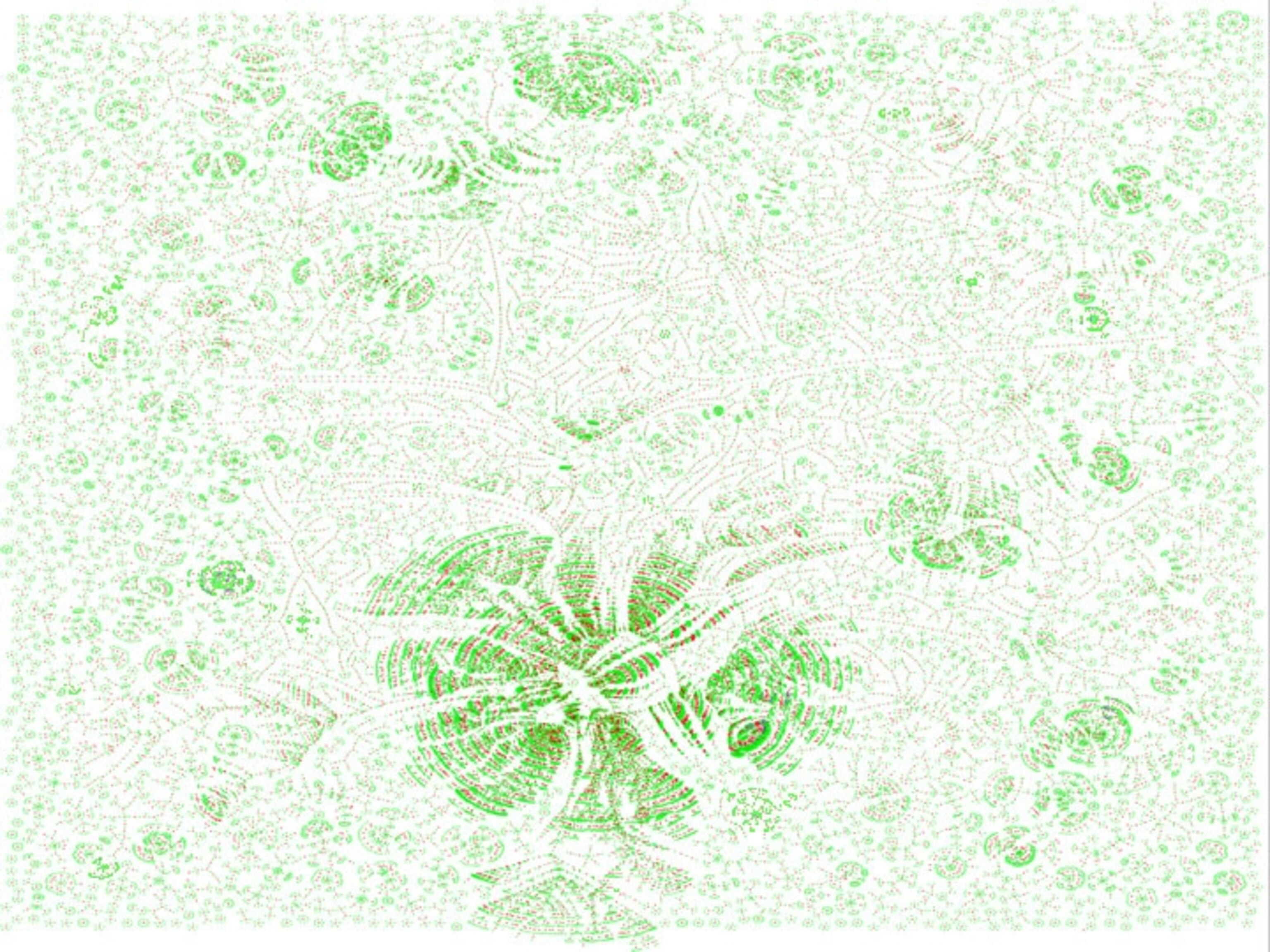

Now, scientists have created a massive family tree of 13 million people that spans 11 generations to try and find answers to larger questions about the human population, from the heritability of long life to the ways whole families dispersed and intermarried over the past few centuries. (Recently, a new DNA map offered some surprises about Irish ancestry.)

The huge new dataset is the largest scientifically validated family tree based on publicly available information, says Yaniv Erlich, a data scientist and computational biologist at the New York Genome Center. His team presents their work in a study published today in the journal Science.

(Genealogy 101: Discover Your Roots)

Working with the data was difficult, because the team couldn’t draw on any pre-existing methods. “Genomic datasets have specific tools, data structures, methods, but we didn’t have any of that for this,” Erlich says. “We were inventing the wheel as we went.” (Find out how DNA is reshaping how we see ourselves and our history.)

As it stands now, the profiles are geographically limited, with 85 percent coming from North America and Europe. And in general, ensuring the accuracy of such a large dataset—especially one collected from independent individuals—is a challenge. Any conclusions drawn from one should be approached cautiously, says Paola Sebastiani, professor of biostatistics at the Boston University School of Public Health.

“In terms of science, you need to have really clean data to make really good, reliable scientific discoveries,” she says. Still, Sebastiani applauds the team’s efforts at validating and analyzing the complex data. “It’s impressive, what they’ve done.”

Growing the Family Tree

Erlich and his team built their family tree using information pulled from the genealogy website Geni.com (Erlich is now the chief science officer at MyHeritage, the parent company of Geni.com). The team started with 86 million profiles and pruned out obvious improbabilities—people that seemed to have three biological parents, for example, or whose information said that their parent was also their child.

Once they’d winnowed down the sample to valid data, they ended up with 5.3 million trees, the largest of which was the 13-million-person set.

It’s time-consuming and difficult to build comprehensive genealogies by hand, Erlich says, which is why the crowd-sourced information was so valuable. It also allowed for a wider range of data sources than past projects: “Most usually use church records from a particular location,” Erlich says.

To check that it wasn’t only people of a certain socioeconomic class uploading their information, the team compared their data to death certificates from the state of Vermont. About a thousand of the people with profiles in the dataset overlapped with the Vermont records, and that chunk included the same traits as those from the entire state. This indicates to the team that their data reflected the population at large, at least for that state.

The team then selected questions around longevity and family dispersal to test the utility of their family tree, Erlich says. First, they compared the distances between the birthplaces of married couples to the familial relationship of that couple across multiple generations. Between 1650 and 1850, married couples were, on average, fourth cousins.

Theories in evolutionary studies suggest that the farther apart spouses are born, the lower their genetic relationship will be. But while the rise of railroad travel in the early 1800s increased that distance for people born between 1800 and 1850, married couples were actually more related during that time period. Genetic relatedness only dropped off in the following decades.

Based on those results, the authors suggest that cultural changes, not transportation changes, made people stop marrying their cousins, although they aren’t ready to speculate about what those cultural factors may be.

Untangling Long Lives

The team also analyzed three million pairs of relatives in the dataset (the entries that had an exact birth and death date), to look for patterns in longevity. They found that heritage contributes about 16 percent to longevity—around 10 percentage points fewer than the 25 percent commonly cited in research on long life.

But Sebastiani, who studies longevity and human aging, says not to overinterpret that conclusion. “There’s a lot of confusion about the definitions of longevity,” she says.

Defining it broadly and looking at individuals living to their 80s and 90s does generally lead to results showing a low genetic contribution. However, for people who live to be over 100, genes begin to emerge as a significantly more important factor, Sebastiani says. But people who live that long are rare.

“That’s why it’s probably not the best to study longevity with big data,” she says.

Geni.com and MyHeritage recently established their own DNA test, and Erlich says future work could map genetic information that people provide through that product onto the existing genealogy data.

Also, the family tree Erlich and his team built is publically available, and he’d like to see other researchers take advantage of the resource to answer any number of genealogical and scientific questions.

“We hope people use it,” he says. “You can look at local disasters, individual families, anthropological questions, fertility rates—the data could be used for all of those things.”