Actress Jane Alexander Tells Tales of Wild Things and Places

“Conservation changed my life,” says the movie star.

Jane Alexander starred in films like All The President’s Men and Kramer vs. Kramer and passionately defended the arts as chairperson of the National Endowment for the Arts, but since childhood she has had another passion: nature and conservation. In her new book, Wild Things, Wild Places: Adventurous Tales of Wildlife and Conservation on Planet Earth, Alexander shares a lifetime of travel to places as farflung as Bhutan and Belize, where she encountered some of the world’s most endangered species.

Talking from New York, she describes why conservation is a spiritual belief; how she traveled up the Amazon with a group of singers and actors; and why, of all the places she has been, her home patch on Nova Scotia is closest to her heart.

You are famous for being a movie star. But you have had a parallel life as a conservationist and nature lover. Talk about the relationship between the two.

My two passions are art and nature. Nature's the great creator—Mother Earth, God, Allah, whatever you want to call it—with more imagination than anything we human mortals can come up with. But we do pretty well in the arts. So I look at the two as not dissimilar, except the natural world is so much bigger. “There's more in heaven and earth, Horatio, than is dreamt of in your philosophy,” says Hamlet. And that's how I think of it.

You say your “life as an adventurer began at three years old.” Talk about your early life in Massachusetts and how it inspired you to become involved with conservation.

My mother was from a Nova Scotian family. She had grown up in a rural area, which was also by the ocean, so she was very comfortable around the natural world. She named the birds for me from a very early age and taught me about things like sea cucumbers. During the war years, my dad was a surgeon with the Fifth Army hospital in Europe, and we lived with a family who rented the Olmstead house. This is Fredrick Law Olmstead's house in Brookline, Mass., which he built and where he created the original landscaping and gardens. That was my introduction to beauty.

You write, “Conservation is an attitude, a spiritual belief or regulation.” Unpack that idea for us.

By attitude I mean, as George Schaller, the eminent field biologist, has taught me, that conservation is not an event, it's a process. In other words, if you have the attitude that everything you meet in the natural world and life has its own reason for being, and you're not there to destroy it, then it becomes an attitude about life. I approach all of nature and what it brings to me every day as something wondrous and something to be greeted.

The spiritual belief is that this is far greater than anything we can comprehend. As E.O Wilson says about spiders and tiny things in the soil, they are the things that run the world. We cannot comprehend the connectivity that makes it all work. We heedlessly go out and spray some Roundup to get rid of whatever it is that's eating our plants. But we don't know what the creatures it will kill might be doing in the soil.

Conservation also has to be regulated. As Tom Lovejoy, the ecologist, has said—I'm paraphrasing—we are heedlessly destroying the very Earth, our home, which we need for everything in our lives, and so we have to manage the planet. That's where regulation comes in. It begins at home, with each one of us understanding that we have to help in the effort to make the Earth whole and not abuse it. We also have to make it a political issue. We have to put pressure on our local politicians, our state and federal government, and ultimately, global institutions.

U.S. Wildlife Services comes in for some particularly vehement criticism in your book. Explain what they are doing wrong.

U.S. Wildlife Services began as a pest control service in the Department of Agriculture over 100 years ago, for extreme problems with pests in crops. Today, you can go online and see what they have killed in any given year at the behest of private citizens and public entities, and the list is alarming! I mean, I don't see any reason on Earth to kill ravens in the number that they do. In 2014, they killed something like 500 ravens. Why? These are some of the most intelligent birds in the world.

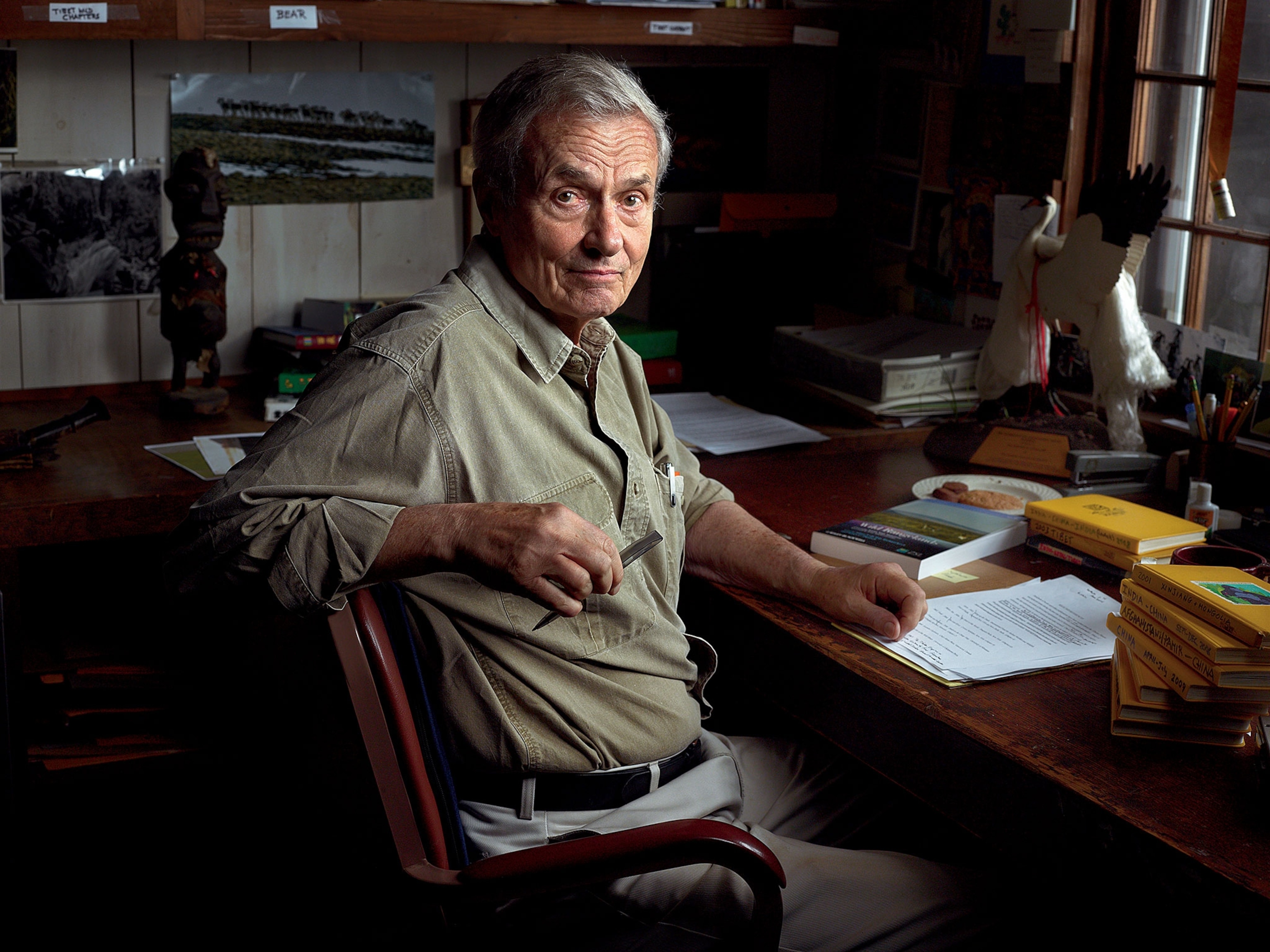

Your book is also a love letter to a number of conservationists who have inspired you. Tell us about George Schaller and why you admire him so much.

There's no one so eminent in the world today in field biology. He is now in his eighties. In his later years, George is seeking the last, great wild places on the planet, where he can travel and be quiet and alone. A few years ago I met him after he came back from Mongolia, and he said, "I drove for a thousand miles and didn't see anyone!"

He loves animals. George is the person responsible for the interest in primates that was taken up by Dian Fossey and Jane Goodall. He was the first to do studies on gorillas in the Congo, lions in Africa, and pandas in China. You name it, George has done it. But most people do not know his name. Everybody has heard of George Clooney. But the name George Schaller is not on the tip of everybody's tongue. And I would like to help right that wrong.

Birding is your particular passion. Talk about that passion and recall for us the moment you saw a monal pheasant in Bhutan.

I've always been attracted to birds and wanted to fly from a very early age. [Laughs.] I was constantly building little wings and jumping off dunes and little cliffs, to no avail. Then I became an actress and, of course, birding and theater are at odds with each other. The early birder catches the bird, and when I was in theater I rarely went to bed before 1 a.m., so for quite a few years I only did sporadic birding. Filming is a much better schedule for birders. Often we are asked to be up before dawn to go into makeup and so on. So I did a lot of birding on location.

Some years ago, my husband and I went to Bhutan with George Archibald, the crane expert, to see the black-necked crane. But I also wanted to see a monal pheasant. There is a pair at the Bronx Zoo. But they're in a shaded cage. I wanted to see one in the sunlight and in its natural habitat. This is a bird that lives up at 11,000 feet, and one morning our guide said, OK, I know a monk in a monastery way up in this area we're in now, so whoever wants to go with me will have a chance of seeing a monal pheasant.

It was a beautiful dawn morning, with steam rising off the grass and the backs of the horses. We wound our way up to this little monastery just as the sun was hitting the red tiled roof. There in the courtyard was a very old monk, feeding about 11 monal pheasants!

Most of them were hens, but there were a couple of males. I got prickles all over my arms. Then the most astonishing thing happened. This one male leapt up to where I was standing on a little ledge above the courtyard. It came right up into the sunlight just in front of me and then walked into my shadow. My heart stopped! This is the bird I most wanted to see and it was as though I had called him in. He came right to me, Simon, and sparkled in the sunlight, just sparkled. The iridescence of each feather looked like it was trembling in the light. It was extraordinary!

Your first trip to the Amazon was on a riverboat with a group of traveling players. Was it as exotic as it sounds?

It was so much fun. [Laughs.] There were about a dozen of us, singers and actors, on this small ship, with 300 passengers. We set out after Carnival in Rio and made our way up the coast, stopping at ancient towns like Salvador, then started into the mouth of the Amazon. It’s roughly another 1,000 miles up to Manaus and, foolish me, I would get up at dawn every day with my binoculars thinking, Oh, I'm going to see the birds on the banks. But what I didn’t realize is that the Amazon is so huge, it's like being on an ocean voyage. Often, you don't see land at all.

One morning, I got up at dawn and saw the Greek captain, up on the bridge, looking around. I said, "Good morning, Captain, what are you doing?" He said, "I'm looking for the boto, the pink dolphin." I said, "Oh, how wonderful!" He said, "The pink dolphin lives in the deep water, so he will tell me the way to go, because we're almost grounding." [Laughs.] Within a few minutes, a pink dolphin curled up out of the water. The captain was very happy. He said that's the way we're going!

You write, “Of all the places I have been, my own backyard, my ‘patch,’ is the place I know and love the best.” Tell us about your love for Nova Scotia and your work as a piping plover guardian.

My family goes back about 260 years in Nova Scotia. They were some of the original founders from Germany, on the south shore. Today, I live on the south shore not far from where my ancestors put down roots, and I feel deeply at home there. It's almost a visceral connection, like it’s in my DNA or something. When my husband and I moved there over 20 years ago, as I do everywhere, I wanted to know whom I'm sharing my home with, what wildlife lives there as well and has predated me by millennia. And there is abundant wildlife: mink, weasels, muskrat, beaver, porcupine, coyote, and plentiful birds. Mostly, because I'm on the ocean, it’s shorebirds and the seabirds I can see from land. So I became captivated.

I became a piping plover guardian about 18 years ago. I help monitor their mating and nest building, and try to educate people not to have their dogs off leash when the piping plovers are nesting and take away trash so that seagulls and crows aren’t attracted and then take the eggs or chicks. In the last two years we've had a lot of predation, but we don't even know what's attacking them, whether it's a fox or an owl or a gull.

At the end of the book, you write, “The glory of life is the incalculable variety of forms and functions that exist.” Unpack that idea for us.

Conservation changed my life, Simon. When I began to fall in love with wild things and wild places, and then meet people like Alan Rabinowitz, who introduced me to the rain forests of Belize, my eyes were opened. I became aware and awake. Scientists say today that in a teaspoon of soil, there can be as many as 10,000 bacteria. We haven't even begun to discover the variety of wild things in the world. It's a constant state of wonder for me.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.