Nanotyrannus likely was a tiny adult dino and not a teen T. rex

Short king confirmed? Together with a blockbuster October study, a new throat bone analysis delivers a “one-two punch” to the 40-year debate over whether Nanotyrannus lancensis was a distinct species.

Nipping at the heels of a landmark study from October that crowned the short king Nanotyrannus as a legitimate dinosaur, a second team of paleontologists has independently reached the same conclusion: the tiny carnivore was no teen Tyrannosaurus rex but its own distinct species.

The new research, published Thursday in Science, comes from an analysis of a small throat bone of the very specimen that set off the decades-old debate. By studying the microscopic details of a peculiar part of the hyoid, called the ceratobranchial, which change with age and comparing it with bones from other animals, such as ostriches, alligators, T. rex, and Allosaurus, the researchers could estimate how mature it was. Their analysis indicated that the fossil was an adult, not a teenager.

The results were surprising, says Caitlin Colleary, a paleontologist at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where the specimen’s skull and throat bone are held, and an author of the study.

“Everything that I had heard when we started the project was that most experts agreed the skull was a juvenile T. rex,” she says, “so I went into it thinking that more than likely we were going to provide additional evidence for that hypothesis.”

Found in 1942 among the rocks of Montana’s famous Hell Creek Formation, the Cleveland skull was originally named Gorgosaurus lancensis for its resemblance to the tyrannosaur Gorgosaurus from the same region. As the years rolled on, however, it became clear that the specimen represented something else. While some experts suggested it was that of a juvenile T. rex, which were virtually unknown in the fossil record at that time, a 1988 study proposed that the skull belonged to a distinct genus of small-sized tyrannosaur and so was dubbed Nanotyrannus lancensis.

Some forty years of debate followed during which the case for Nanotyrannus often seemed flimsy to some scientists. That is until the two research papers published this year.

“This study provides important confirmation that Nanotyrannus is valid,” says James Napoli, a paleontologist at Stony Brook University in New York who co-authored the October study in Nature, but was not involved in the latest paper. “This study elegantly shows that the Nanotyrannus lancensis specimen was at least near maturity at death, and that it therefore cannot be a juvenile T. rex.”

The scientists estimate that an adult T. rex was roughly three times longer than Nanotyrannus lancensis and weighed an order of magnitude more. The research also provides further evidence that Nanotyrannus lancensis was a Late Cretaceous predator that stalked forests and floodplains alongside the voracious T. rex, possibly competing against its young for food.

Deciphering dinosaur throat bones

In 2021, Christopher Griffin, a paleontologist from Princeton University and lead author of the study, wanted to see if throat bones of crocodiles, birds, and dinosaurs could provide insight into an animal’s growth and maturity. He thought a good place to start would be studying modern birds and crocodylians to investigate if the bone might help reveal clues about dinosaur growth.

Around the same time Griffin was beginning his study, Colleary says, she was beginning work as paleontology curator at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History where the much-debated Nanotyrannus skull was kept.

“I didn’t think much about it until I noticed the ceratobranchial sitting in a little box next to the skull,” she says. That bone gave Griffin’s growth study a potential application among dinosaurs.

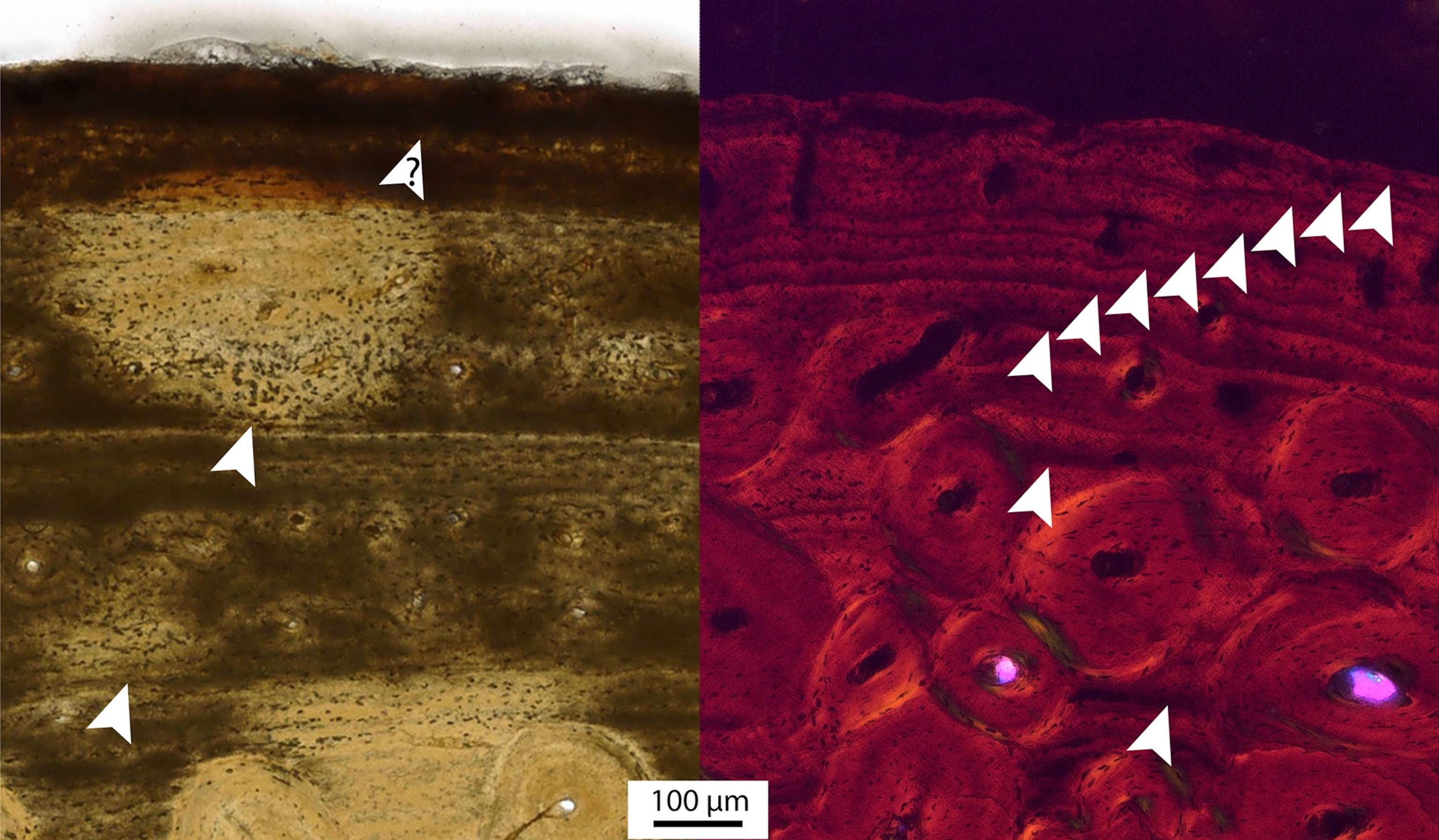

The Cleveland tyrannosaur’s throat bone was challenging to study. Part of the slender bone showed signs of injury, making a portion difficult to interpret. But two other sampled locations along the bone were less ambiguous. The bone tissue had been heavily remodeled and appeared to be compact, different from the messy and more open appearance of bone tissue found in younger animals.

Colleary and colleagues identified the stack of lines in the bone tissue as an external fundamental system, or EFS. The EFS is often taken as a sign of when a dinosaur has effectively ceased growing, which indicated the Cleveland specimen was skeletally mature at death.

Jared Voris, a paleontologist at the University of Calgary who was not involved in the paper, expressed some caution about the findings. He notes that what the researchers identify as an EFS may actually be a series of a different kind of growth ring clustered close together. If that’s the case, then the throat bone might indicate the dinosaur was still growing and was not as skeletally mature as the new paper proposes.

Further study of the known Nanotyrannus specimens like the Cleveland specimen and the “dueling dinosaurs” from Napoli’s paper will test the new identifications. Nevertheless, the revival of support for Nanotyrannus indicates a significant shift in dinosaur science.

Colleary says that she and her colleagues knew about Napoli’s Nanotyrannus research happening in tandem, as it involved CT analysis of the Cleveland skull. As a curator, she says it’s important to her to provide researchers with access to her museum’s specimens and that the new findings together open the door for future studies into the carnivorous dinosaur family.

“More people working on something makes the science so much better,” Colleary says. “To have the two studies come out so closely together really makes me feel like it's a one-two punch for Nanotyrannus.”