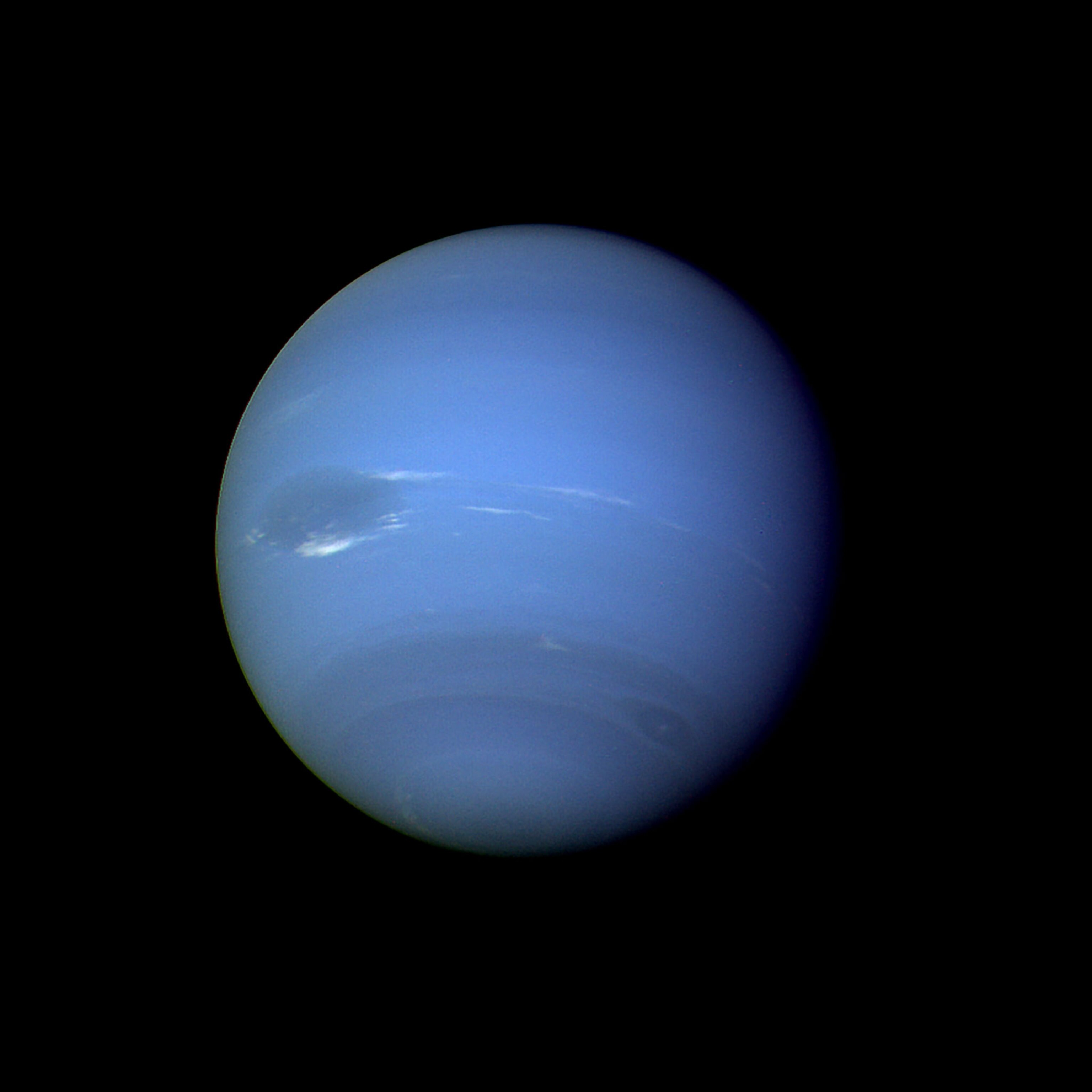

Strange Storm as Wide as Earth Appears on Neptune

The bright tempest is the first ever spotted near the planet’s equator, raising questions about how it formed and persisted.

Neptune’s wild, windy weather has taken a turn for the worse, with a new storm erupting in a surprising spot near the beautifully blue planet’s equator.

Estimated to stretch roughly as wide as Earth, the young storm system is a big, bright cloud that’s probably raining methane ice into the planet’s interior. In recent images from the Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, the cloud appeared to brighten between June 26 and July 2, and it was still roiling as recently as July 25.

Though storms have been seen evolving on Neptune before, such a massive storm has never been seen near Neptune’s equator—the planet’s bright stormclouds generally appear to cluster closer to the poles.

“This one is weird, because it’s really big and it’s not dark. It’s bright, and the bright stuff is probably sort of like cirrus clouds on top of a thunderstorm that’s underneath,” says Bryan Butler of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. “And it seems to be staying steady, for it’s been a month or something now.”

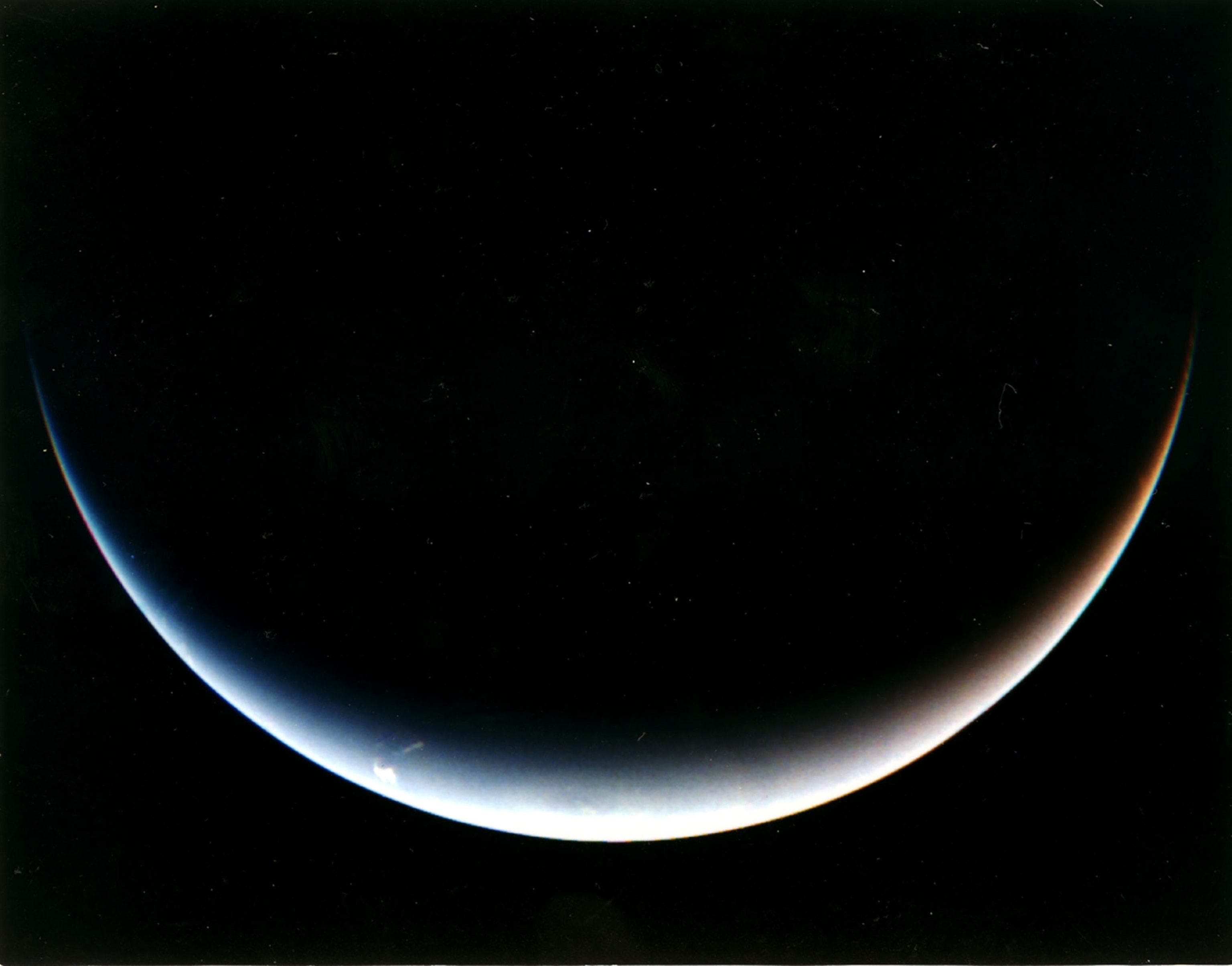

It’s not often that we get to watch tempests evolve on the solar system’s farthest-flung giant planets. Neptune orbits an average of 30 times farther from the sun than Earth, and it has not had a spacecraft visitor since 1989.

That means it’s a world that astronomers know precious little about, but they do know that Neptune’s record-setting winds whip and churn through its atmosphere at more than a thousand miles an hour. The planet’s weather is among the most severe in the solar system, although it’s not clear how the frigid world generates enough energy to fuel its furious winds.

Based on the observations we have, it seems that bright, icy wisps of clouds come and go, as do the dark, giant storms that smear the planet’s face. In 1989, the Voyager 2 spacecraft observed a Great Dark Spot—a roundish cyclone—that rivaled Jupiter’s Great Red Spot in size and bested it in windspeed. But by the time the Hubble Space Telescope swiveled to look at the planet in 1994, that spot had vanished. Instead, Hubble observed a smattering of bright clouds in the north.

When UC Berkeley graduate student Ned Molter first saw this massive cloud through Keck’s eyes in June, he and his advisor Imke de Pater thought it might be the same storm Hubble saw 28 years ago.

It wasn’t. Now, the team is working on figuring out how such a humongous cloud emerged, formed, and stayed put near the planet’s equator.

“Since it must have been around for a few weeks at least ... something must hold it together,” de Pater says.

One possibility is that, like the titanic storm that marched across Saturn’s face in 2011, this cloud is simply a feature of the upper atmosphere that could ultimately dissipate.

Another intriguing idea is that the storm is anchored to a deep, dark vortex that dredges up warmer gases from the planet’s interior. As those gases meet the planet’s frigid atmospheric fringe, they condense into clouds that shine brightly to Keck's telescopic eyes.

”If it’s tied to this underlying thunderstorm, then it will probably be long lived,” Butler says. “You can look underneath the clouds by doing radio observations, because that sees deep down into the atmosphere. The problem is, it’s tricky.”

Still, solving some of the mysteries about planets in our cosmic neighborhood could help astronomers better understand the thousands of alien worlds found across the galaxy thanks to planet-hunting spacecraft like NASA’s Kepler telescope.

“The thing that’s important about the ice giants is that the bulk of the planets that Kepler has found are ice giant size,” says Butler. “If we’re going to understand exoplanets at all, we better understand Uranus and Neptune.”