Newly discovered rat that can’t gnaw or chew

If you only looked at mammals, you could reasonably believe that the chisellers have inherited the earth. Of all the various species of mammals, forty percent are rodents. Rats, mice, squirrels, guinea pigs… all of them have the same modus operandi. They gnaw their way into their food with self-sharpening chisel-like teeth.

Whether tiny gerbil or huge capybara, rodents eat with the same special teeth. The upper and lower jaws each have a single pair of incisors that grow continuously through their lives. The front of each tooth is made from hard enamel, while the back is made of soft dentine. As the rodent gnaws, the incisors scrape at each other, and the dentine wears away faster than the enamel. This creates a permanently sharp edge, useful for cracking into wood, nuts and flesh alike. Once gnawed, the rodent passes its food to the back of their mouths to be chewed by grinding molars.

But on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, Jacob Esselstyn has discovered a new species of rodent that radically departs from this universal body plan: a “shrew-rat” that he calls Paucidentomys vermidax.Its name –a mash-up of Latin and Greek—gives a clue to its lifestyle. It means “worm-devouring, few-toothed mouse”.

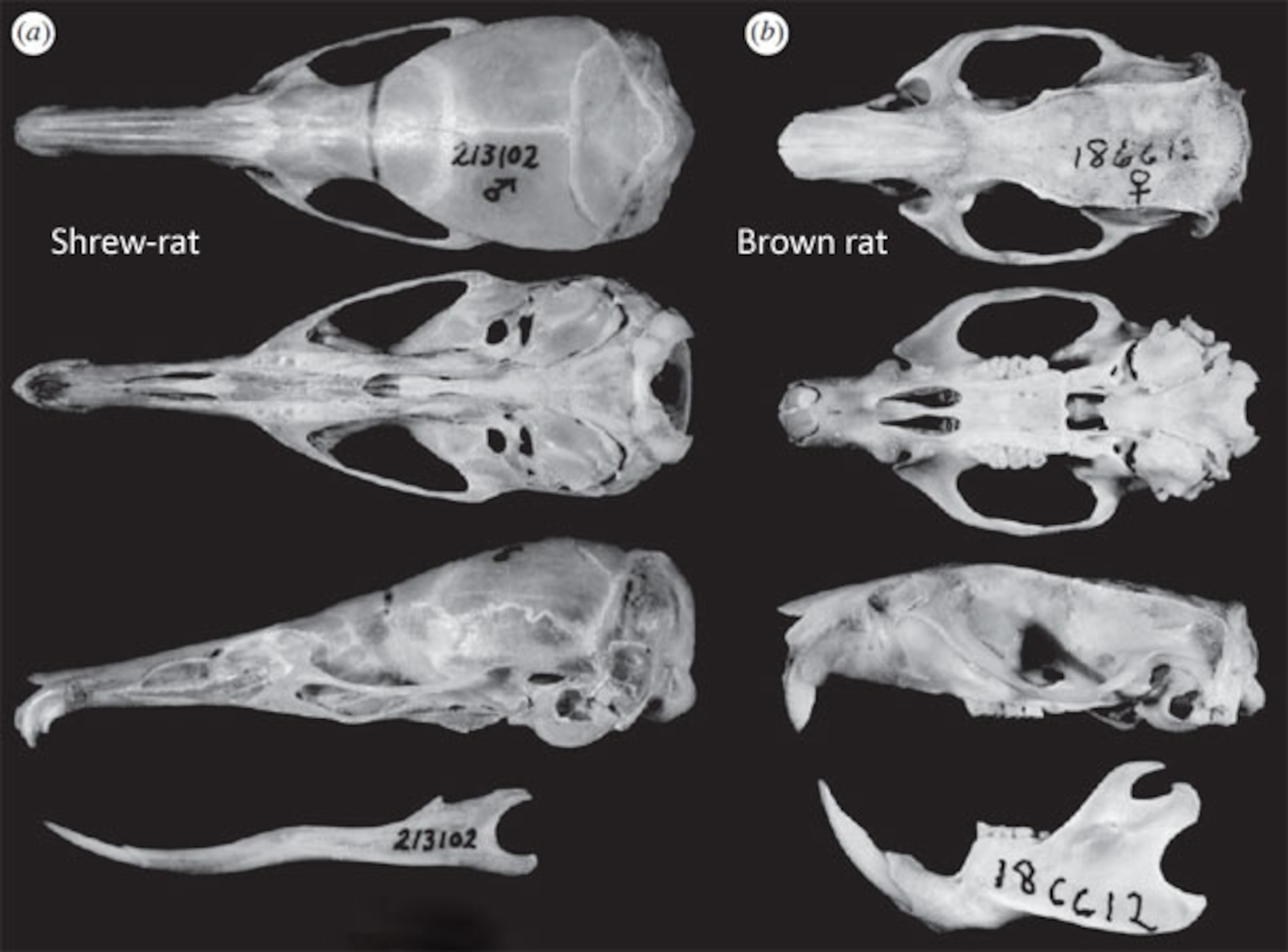

The shrew-rat is just a few inches long, with small eyes, large ears, and a soft coat. Its most distinctive feature, however, is its long snout, reminiscent of the distantly related shrews that it is named after. At the end of the snout, the lower jaw has the usual flat-edged incisors, but the upper jaw has a pair of bicuspids (like the ones next to your pointed canines). And that’s it. Unlike every other rodent, this one has no molars—just four incisors, nothing else.

There are other shrew-rats in Indonesia and the Philippines, and while all of them have lost the ability to gnaw, none have features quite as extreme as Esselstyn’s new find. (All of them, for example, have molars.) They’re an odd group, united by their common long-snouted appearance rather than by any evolutionary similarities. Rather than forming one unified branch of the rodent family tree, the shrew-rats represent twigs on separate branches. They evolved their odd shapes independently.

Shrew-rats typically eat earthworms and other soft-bodied creatures that don’t require gnawing teeth. That’s exactly what Esselstyn’s new species does. He collected two of the animals in March 2011, and when he examined the stomach contents of one, he found earthworms and nothing else.

Esselstyn thinks that the shrew-rat has lost the ability to chew and gnaw because it only eats soft prey. It only needs teeth for capturing food rather than processing it. As such, it has lost everything except for two front incisors, used to snag worms and cut them into easy-to-swallow pieces. Like the lost limbs of snakes and whales, the missing teeth of the shrew-rat are a reminder that evolution disposes of body parts that are no longer useful, and that those same losses can open up new opportunities.

Reference: Esselstyn, Achmadi & Rowe. 2012. Evolutionary novelty in a rat with no molars. Biology Letters. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.0574

Images from Esselstyn et al.