A National Geographic expedition led by explorer Robert Ballard has found what is believed to be the remains of John F. Kennedy's PT-109. Experts from the U.S. Navy recently confirmed the May 2002 find is most likely the World War II patrol boat.

PT-109 sank in the Solomon Islands when a Japanese destroyer sliced through it, setting into motion the survival odyssey that became a cornerstone of the Kennedy legend.

Nearly 60 years ago a Japanese destroyer materialized out of a moonless night and smashed through PT-109, sending 26-year-old skipper John F. Kennedy into fiery waters to save his crew. Six weeks ago explorer Robert Ballard patrolled the same South Pacific beat, searching for the ruins of that seminal 1943 night.

What Ballard found some 1,200 feet (360 meters) down—a torpedo and torpedo-launching tube caked in coral and rust—may lack the majesty of his most famous find, Titanic. But, he said during the expedition, "I'm very pleased, because it was a real needle in a haystack, probably the toughest needle I've ever had to find."

At 5 by 7 miles (8 by 11 kilometers), the search grid is small by Ballard's standards. But it bristles with false targets such as rocks and other war wrecks, and much of the seafloor here is covered with dunes he likens to an undersea Sahara.

Due to the shifting dunes, "we were lucky just to see the tubes uncovered," said Dale Ridder, a weapons and explosives authority on the U.S. Marine Forensics Panel. "At another time we might not have even gotten that."

The scant remains, given their location and telling details, were enough to convince Ridder on the day after the May 22 find. "We have torpedo tubes off of one PT-109.No doubt!" he shouted while reviewing video captured via remotely operated vehicle (ROV). "This is it!"

The final word, however, had to come from the U.S. Navy.

The Evidence

Recently, U.S. Naval Historical Center curator Mark Wertheimer and underwater archaeologist Claire Peachy convened at National Geographic's Washington, D.C., headquarters. At a closed-door screening of wreck footage, they were joined by Welford West, who as a World War II torpedo man helped rescue the PT-109 crew. Ballard, a National Geographic explorer-in-residence, sat in via telephone.

National Geographic did not want to disturb PT-109's remains, and without artifacts recovered from the site, the Navy could offer only conditional confirmation. Still, Wertheimer concluded, "Given all the evidence presented, it appears to be the PT-109." That evidence includes the find's location, the types of torpedo and torpedo tube, and a cranking mechanism.

First, location: No other PT (patrol torpedo) boat was lost in the search area. Plus, the location of the find is consistent with historical accounts of the PT-109 bow's drift. (The stern, or rear, sank at impact.)

Following the course established by an isolated Australian coastwatcher the day after the collision "and Kennedy's own accounts into that night, it would place the bow section at the southeastern end of Blackett Strait near the entrance to Ferguson Passage," said Ballard. "This is exactly where we found PT-109."

Second, the types of torpedo and tube found—Mark 8 and Mark 18, respectively—were used mainly on PT boats during World War II.

Third, a PT-boat training gear—a cranking mechanism used to position a torpedo tube for firing—was identified next to the tube at the wreck site.

Where Is the Rest of the Boat?

That last detail—the training gear—combined with readings from sonar (which can penetrate the seafloor) have Ballard convinced at least part of the rest of the bow is buried and connected to the tube.

The gear is positioned as it would have been on an intact boat. And the search team tried to nudge the gear with an ROV attachment. "It didn't budge," said Ballard during the expedition. "That says it's intact."

In addition, "Our sonar record is seeing much more than our eye is seeing," said Ballard. Sonar showed a target some 7 meters (23 feet) wide, roughly the width of a PT boat.

If buried, most of the largely wooden hull would likely have disintegrated or been eaten by woodborers in these sand-scoured, oxygen-rich waters. For the most part, only metal would remain: engines, gas tanks, torpedo tubes.

And the stern? It sank at the collision site, approximately five miles (eight kilometers) north of the bow site—if it remained intact at all. "This was probably so utterly crushed in the initial collision," said Wertheimer, "that you won't find much of anything recognizable." Not that Ballard was looking for long.

In what he calls "a snap decision," Ballard gave up looking for the stern on about the fourth day of the weeklong search. It was, he said, "the pivotal point" of the expedition. Had they kept searching for the stern, he said at the end of the expedition, "We would be going home without a success."

How They Found the Wreck

Ballard's initial target was PT-109's stern. It would be easier to find, the logic went, because it went down at a known location, whereas the bow floated at least 12 hours, according to crew accounts, before sinking.

The search began with methodical, round-the-clock sonar scans of the predetermined search zone. Sonar showed "thousands and thousands of targets that fit the description of PT-109," said Ballard—most likely shipwrecks, ridges, and boulders.

"I knew it was hopeless," said Ballard. "So I said, Now what am I going to do? Well, the only thing left was to go after the bow. And that proved to be a very nice decision," he laughed.

In his newly narrowed search area—about a mile and a half square (four kilometers square)—Ballard found "the best target we saw in our whole survey." He added: "Some people thought it was a barge. We said, let's go look at a barge anyway."

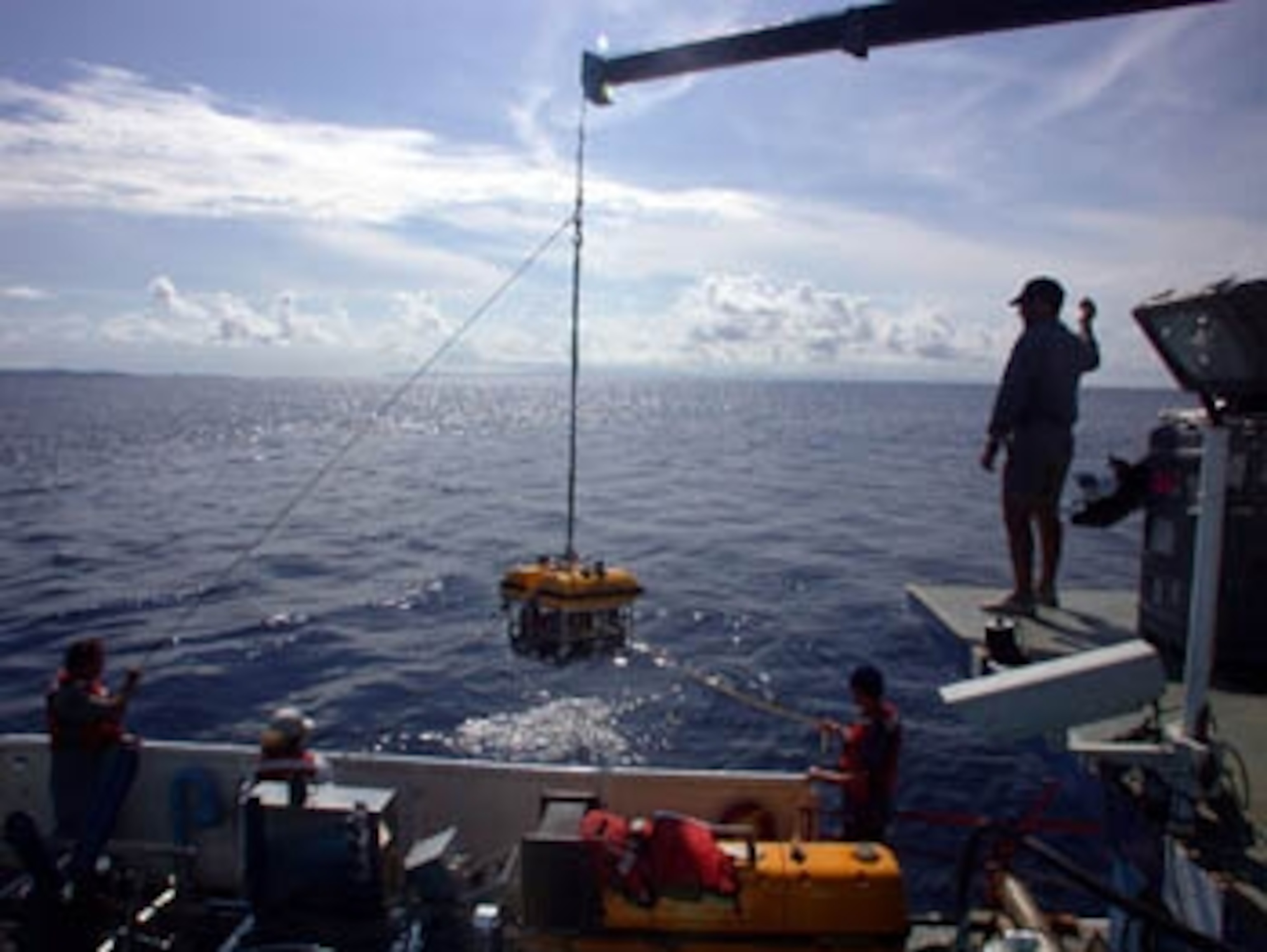

Target secured, the team deployed their two ROVs: Little Hercules, used primarily for filming, and Argus, used mainly as a lighting rig for "Herc."

Three days before the charter expired on their search ship, the team got visual confirmation: "It turned out it wasn't a barge at all," said Ballard. "I'm glad we looked."

The Story of PT-109

Asked why he wanted to look for the PT-109 in the first place, Ballard said, "Many young people these days don't even know the story of PT-109. [Kennedy] emerged from this experience the person who went on to become the President of the U.S."

Asked how he became a war hero, Kennedy once answered, "It was easy—they sank my boat." But the sinking may have been the only easy thing about it.

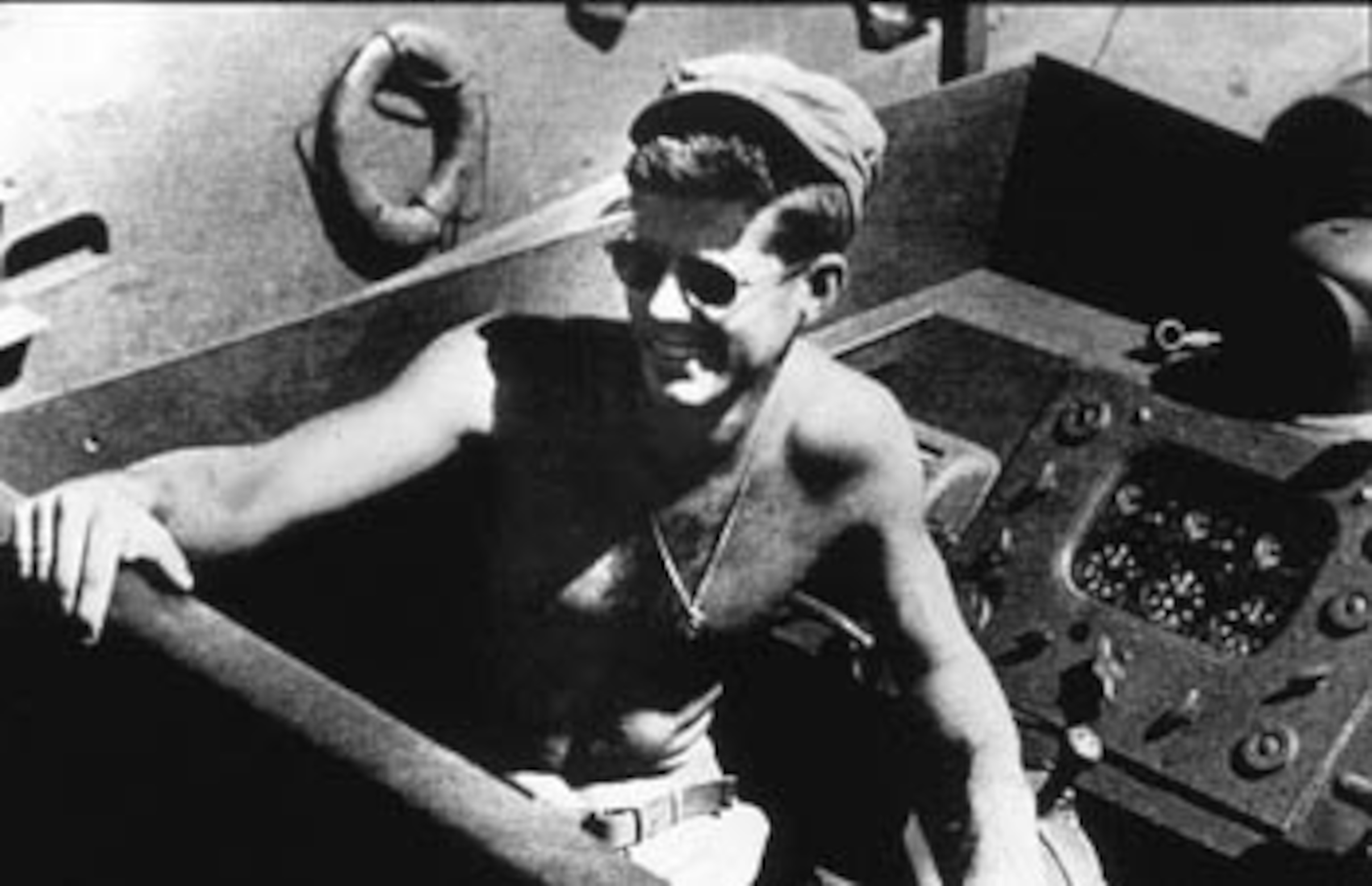

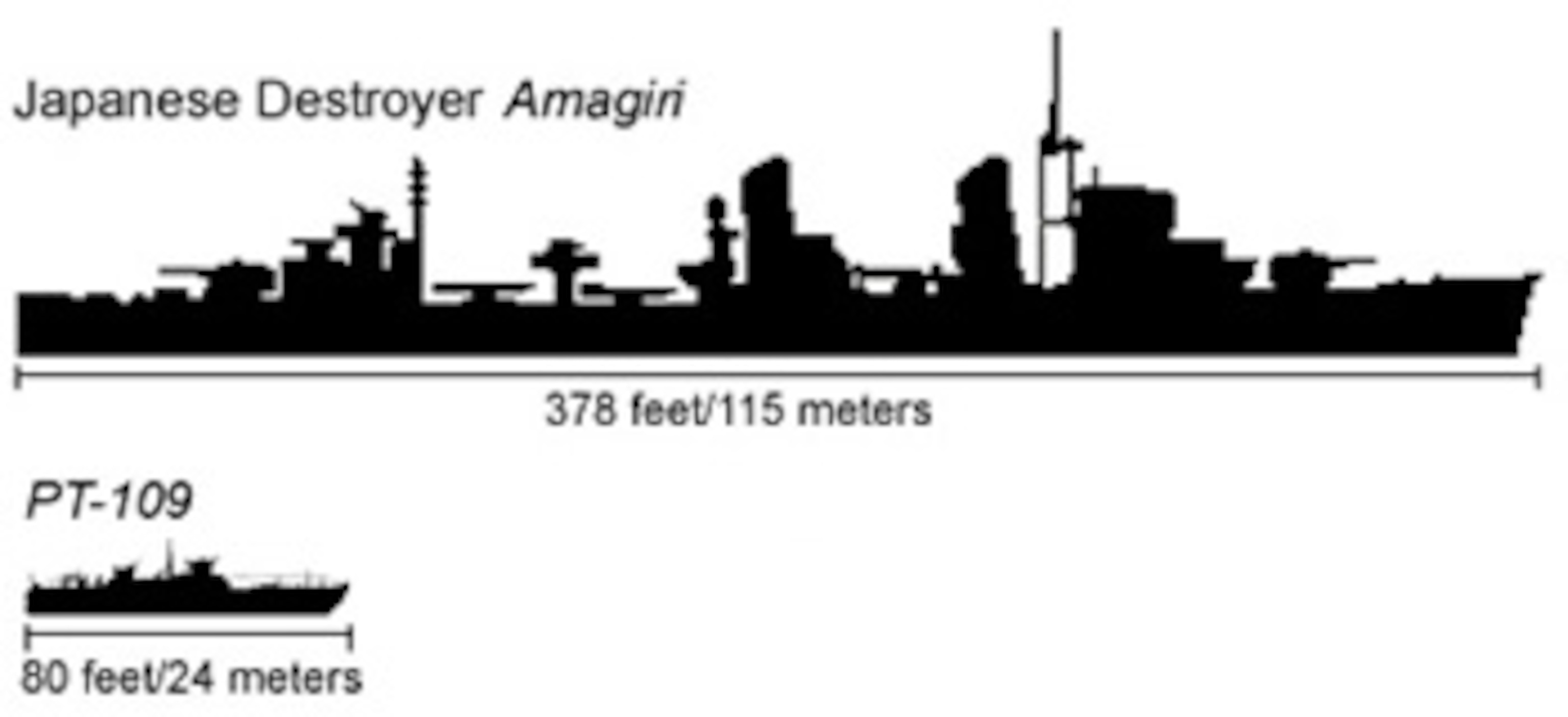

The dashing new lieutenant was likely drawn to the adrenaline and independence of PT service. With crews of 12 to 14, the high-speed, 80-foot (24-meter) "mosquito boats" nimbly harassed much larger enemy ships. And in World War II, PT service was nearly the only way a relatively new officer could skipper his own boat.

When Kennedy took charge of PT-109, on April 25, 1943, he was already a millionaire heir, society figure, and ambassador's son. But fame and fortune were scarce comfort to him on August 2, 1943.

That night at about 2 a.m., the Japanese destroyer Amagiri, by accident or by design, bisected the much smaller PT-109, killing two of Kennedy's crew.

Kennedy spent the rest of the night helping rescue injured and wave-tossed crew members. By dawn the survivors were all clinging to the still-floating bow.

By afternoon they were making a several-hour swim—the strong towing the injured—to a deserted island. Despite a back injury, Kennedy himself pulled the worst case, tugging the sailor's life vest with his teeth.

The following days (see detailed time line at right) saw several fearless attempts to be rescued. The men were weary with starvation and thirst, when they were eventually rescued by Solomon Islanders loyal to the Allies.

The islanders could operate in daylight without arousing Japanese suspicion, and many served as scouts for Allied coastwatchers operating behind enemy lines. Two of them helped deliver to a coastwatcher a coconut Kennedy famously carved with a rescue message.

After receiving messages from the 109 crew, the coastwatcher radioed the PT base to arrange a rescue. Six days after their stranding, Kennedy and crew were safe aboard a sister ship, PT-157.

The PT-109 survival story passed into popular culture and became perhaps Kennedy's greatest political asset.

Kennedy the President had a PT-109 float in his inaugural parade, doled out 109 tiepins to visitors, and kept his medals on permanent display. And on his Oval Office desk sat, lacquered and almost illegible, the world's most important coconut.

Raise the Wreck?

Despite its sorry state, PT-109 is an icon of courage and presidential glamour. Should it be raised? Ballard isn't biting.

"I'm actually content to leave it buried," the explorer said. "I think it's a grave, and it's apropos—showing us enough to know but burying the rest."