Inside the quest to build the ultimate nonalcoholic beer

Scientists in Belgium—that celebrated bastion of ancient beer culture—are harnessing genetic breakthroughs and machine learning to reimagine how great booze gets built. Here’s how their revelations in the lab could transform the global beer industry.

The secretive beer lab inside the headquarters of the world’s biggest brewing company doesn’t often allow visitors. But today AB InBev has something it would like to show off. So David De Schutter, the head of AB InBev’s Global Innovation and Technology Center—the official name of the beer lab—is showing me around the squat black building on the outskirts of Leuven, Belgium, about a half hour east of Brussels. Belgium is one of beer’s ancestral homelands. Across the street from the lab is the brewery that makes Stella Artois. Leuven is crisscrossed by canals originally built by brewers to move their product. This is a beer company in a beer town in a beer country. So the office building has a dedicated tasting room. With a kegerator. When we get there, De Schutter’s colleagues have arrayed some snacks along with 12 different kinds of beer for me to try. That’s enough beer to give Homer Simpson pause. Taste-testing alcohol typically demands small sips, copious notes, and a lot of hepatic fortitude. But not today, because most of these beers are alcohol free. This might come as a surprise. After all, in addition to Stella, AB InBev owns Budweiser, Corona, Modelo, Michelob, and several other well-known brands. It is to beer what Google is to the internet or ExxonMobil is to oil. And beer is generally understood to be alcoholic.

Yet here I am, taking a skeptical sip of Michelob Ultra Zero and Corona Cero, AB InBev’s state-of-the-art, flagship nonalcoholic beers. As a technical matter, it’s not hard to get the alcohol out of beer, but it’s hard to make the result taste good. You tend to get something that is, to paraphrase the author Douglas Adams, almost but not quite entirely unlike beer. AB InBev introduced Michelob Ultra Zero in early 2025 as the worldwide market for NA beers was quickly ramping up, and these were the best-tasting examples its science could deliver. They were … fine. De Schutter is proud of these beers, but he must know they’re merely fine.

Then he offers me a bottle of the new state of the art. This is AB InBev’s latest biotechnological innovation: nonalcoholic Negra Modelo, made with something dubbed “smart yeast”—a new strain of the essential microorganism that makes all beer possible. Modelo is typically bottled at 5.4 percent alcohol. Smart Yeast Modelo, as I came to call it, clocks in at 0.4 percent. At the moment, Smart Yeast Modelo is available only in Mexico. It’s basically still in beta.

Modelo is my usual order with Mexican food, so I’m familiar enough to detect deviation from spec. In beer terms, Negra Modelo is a Munich-type dunkel, mahogany-colored and malty. I take a whiff. It has the same roasted, hoppy aroma of Modelo. Now a sip: It has a good balance of sweeter malt and bitterness. The mouthfeel seems a little thin, maybe, slightly too astringent. It wasn’t quite Modelo, but it was eminently drinkable.

De Schutter takes a sip too, then looks at me. “We’re super excited about this,” he says.

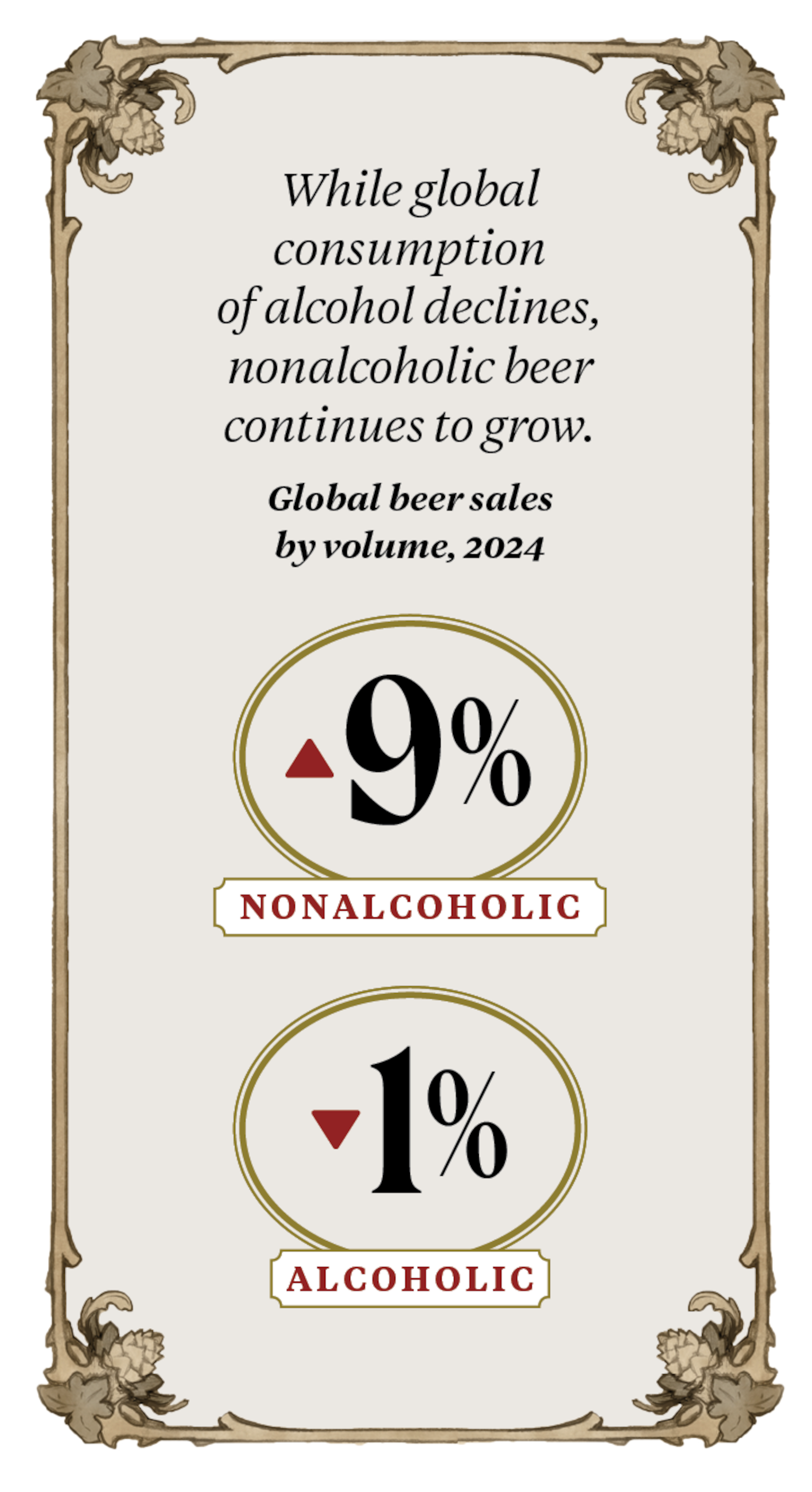

In 2024, AB InBev made $60 billion and produced 15 billion gallons of beer. But today, for the first time, after thousands of years of uninterrupted success, the nearly trillion-dollar beer industry is in decline. In beer-drinking epicenters like Belgium and Australia, consumption has gone down by 50 percent in the past half century. Beer consumption in the United States is down 25 percent since 1980; in 2023, Americans bought less beer than in any other year this century.

Younger people, in particular, are drinking less, and no one’s quite sure why. It’s happening in places where marijuana is legal and where it’s illegal, so that’s not the culprit. They’re certainly more health conscious and more skeptical of even moderate amounts of alcohol. A recent report from Rabobank hinted that Gen Zers spend less on booze because they have less money overall. But then why are canned cocktails surging? Do Gen Zers really prefer a tall can of salted caramel banana piña colada?

What’s abundantly clear is that beer is taking the hit category-wide, from ultrabitter West Coast IPAs to English pub-style ales, with just one glaring exception: nonalcoholic beer. Sales of NA beers, defined as under 0.5 percent alcohol by volume, were up 29 percent in 2024 in the U.S.

The marketing team at AB InBev saw this coming. For years, it has seen strong sales of so-called light beers, lower in calories and with less alcohol than a standard brew. And from a business perspective, nonalcoholic beer is all upside. “It’s a premium, high-priced product,” says Dave Infante, author of the booze-industry newsletter Fingers. And in the U.S., the companies don’t pay excise taxes on beer with no alcohol, “so the margins are really attractive.” NA beer could be the win that the industry sorely needs now.

So AB InBev’s scientists went back to the lab, hunting for a new way to make beer without alcohol that tasted as good as beer with it. They found a lot more—something that might explain not just how to make a new beer, but why people like it in the first place. If the science of beer-enjoying has a unified field theory, this was the god particle.

The key was the yeast. Yeast ferments—which is to say, it eats sugar and poops out carbon dioxide and alcohol. That is its whole ontological deal. But what if you could engineer a yeast that doesn’t make alcohol at all? It would be a biochemical oxymoron—like a tree that grows bacon. In theory, such a yeast could be a building block for NA Negra Modelo and every other label on InBev’s shelf.

To create this mycological unicorn, the company turned to one of the world’s foremost scientists of beer—a yeast whisperer of sorts, named Kevin Verstrepen, whose lab happens to be on the other side of town from AB InBev HQ. Led by its mad beer scientist, the company embarked on a quest almost Frankensteinian in its ambition and implications, with the potential to unlock not just nonalcoholic beer but also NA wine, gin, whiskey … The god particle of beer holds the potential to be infinite in its beneficence.

Get some grain; usually barley. Malt it—that is, let the seeds germinate, so they start making enzymes that convert their starch into sugar. Grind that up and put it in boiling water. Wait. Add yeast. Wait. Congratulations: You have made beer. Brewers are lovely nerds who delight in making things complicated, but basically, that’s it.

Yet for all that simplicity, beer is also deceptively complex. Amid a zillion variations of method and recipe, any given beer comprises not only the fizz of carbon dioxide and the sting of alcohol but also flavors drawn from the grain, from the bitter flowers of a plant called hops—and from the biochemical transformations of yeast.

Yeast—specifically, Saccharomyces cerevisiae—is found just about everywhere on Earth. It’s the key to the foods that civilized humankind. Bread, for one; beer, for another. The first beerlike drinks date back some 8,000 years, though brewers didn’t know what yeast was until the mid-1800s. Early brewers simply relied on the alchemy of fermentation to turn little more than breakfast porridge into a flavorful beverage that also made people feel good, and sold for good money. If yeast didn’t exist, we’d have to invent it.

By 2012, AB InBev had determined that the combination of flagging beer consumption and flavorless NA beer represented both a business and biotechnological opportunity. There was just one problem: Nonalcoholic beers have historically been, in a word, bad. Brewers made “near beers” by shortening fermentation time. The yeast made less alcohol, and the results tasted like watered-down Wheaties.

“No-alcohol beer was quite stagnant,” says De Schutter. “Nobody had really put effort into R and D.”

As De Schutter’s team started digging in, the tech improved. Membranes and reverse osmosis, like water purification, could filter out alcohol. Heating beer with steam would cause the alcohol to evaporate. This new generation of NA beer was better but still had some problems. Beer contains proteins, and heating them produced dimethyl sulfide—the aroma of boiled vegetables, “components that are not necessarily part of the fresh beer aroma,” De Schutter says, with a diplomat’s touch. “So we set ourselves the goal, the dream, to make no-alcohol beer as good as regular beer.”

That’s a tall order. AB InBev is going to put NA beer into a bottle that says “Budweiser”? Really?

De Schutter insists this isn’t about replacing Bud for a beer-agnostic generation. It’s about building something new. “The way we measure that is with consumer tests,” he says. “ ‘As good as’ is just probing for preference in the consumer panel. If, statistically, your beer is ‘as good as’ the regular beer, you achieve your goal.”

Craft brewers would, let’s just say, beg to differ. They’re nerds! They make what they want to drink, whether that means a classic British stout or aged, sour beer fermented with ambient funky yeast, bittered with hops that taste like bong water, and finished with a dash of sriracha. They are making, and I say this in all sincerity, drinkable art. AB InBev is playing a very different game. Its NA beers can’t be merely “good.” They have to be widely appealing. Chemically stable even amid the vagaries of international shipping. Consistent, year after year.

When it comes to nonalcoholic beer, that’s really hard to do. Sure, 95 percent of a beer is not alcohol. But that last 5 percent has always been the obstacle between a premium, scalable NA beer and wet breakfast cereal.

Most of what we call “flavor” is actually smell. The tongue is a blunt detector of salt, sour, bitter, sweet, and the meaty flavor of umami, but the nose senses a far more subtle spectrum. Alcohol lights up all of that, plus more. It is an aroma molecule: a flavor and a smell. It also triggers heat receptors in the mouth, and it has an unctuous mouthfeel—what a connoisseur might call “body.”

So its absence leaves a big hole. Adding grains like oats and rice can amp up mouthfeel, but from the beginning of their foray a decade ago, the AB InBev researchers have been determined to stick with their beers’ original ingredients. As a first step in spackling over the gaps, they tweaked their brewing process to preserve long-chain carbohydrates called dextrins—they’re nearly tasteless, but they add viscosity.

To get alcohol out, De Schutter’s team experimented with a variety of emerging techniques, all of which required expensive new equipment and lots of energy and water, just to produce results that always lacked a certain je ne sais quoi. Except scientists do know quoi: Dissolved within the alcohol are hundreds of other beery flavor molecules, from the banana smell of isoamyl acetate to the clovish spiciness of 4-vinyl guaiacol. These volatile aromatic molecules give beer its flavor, and many are “secondary metabolites” that yeast produces during fermentation. Remove the alcohol and you remove them too.

Only one solution was available: Add them back in afterward. Brewers working on NA beers squirted “natural and artificial flavors” into the products to cover a lack of flavor or mask their faults. More intense styles could pull this off with more panache—the toasty/coffee aromas of a stout like Guinness or the tropical-fruit hoppiness of modern India pale ales. “We can add other components that make it have more mouthfeel. We can add alcohol-adjacent chemicals,” says Scott Lafontaine, a food chemist at the University of Arkansas who studies beer. “That’s where understanding fermentation and yeast biochemistry are essential to creating a beerlike-adjacent product.” (Lafontaine’s research suggests that the more a beer tastes like soda pop, the more Americans will like it. Not this American, for the record.) And sure, the best beer-adjacent products can be quite good. But in my experience, they lose something as they sit in a glass. They taste good at the top, fine in the middle, and then … well, I rarely finish them. Without the alcohol matrix, those flavors fizz away more quickly.

De Schutter’s team decided on a different approach. Yeasts eat sugar and excrete alcohol and all those other flavors, secondary metabolites. But what if a yeast made only those other flavors?

AB InBev needed a bacon tree. Luckily, the world has a lot of yeasts. The lager-style beers, for instance—light, clear, and popular, like Budweiser—aren’t made with S. cerevisiae but with a different species, the hybrid S. pastorianus.

This is why breweries are so careful with their special yeast strains. When strains reproduce, they mutate. So brewers keep their yeast frozen and only scrape out tiny samples at a time. The original batch must never break containment. “For me, the yeast is the soul of the beer,” De Schutter says. “If you want to make a Stella Artois, you need to have the Stella Artois yeast.” The same goes for any of the other beers in the AB InBev line.

With human nudging, yeasts have evolved into wolfish apex predators that feast on the range of sugars we extract from grains, from smaller, simpler ones like glucose and fructose to bigger, more complex ones like maltose and maltotriose. Brewing yeasts eat them all. But more demure species and strains exist too. These Pomeranians of the yeast world can’t handle the big sugars. They still ferment, and they create interesting aromatic molecules, but they produce far less alcohol. De Schutter’s team tried one of these alt-yeasts back in 2017, a yeast from the genus Pichia. During my visit, De Schutter offered me a small plastic cup filled with the result: a sweet, beerlike liquid with strong notes of apple Now and Later candy. It was the wrong yeast.

The NA yeast of the future would be just as important to AB InBev as the one that makes Stella. But De Schutter and his team didn’t have the background to find it. He needed help, someone with a uniquely tailored biochemical expertise. He needed a yeast whisperer.

Kevin Verstrepen is the director is the director of a lab with a name that’s going to make you wish you chose a different major in college: the KU Leuven Institute for Beer Research. He didn’t set out to pioneer beer flavor. Pursuing a biological engineering degree with notions of delivering the next world-changing vaccine, he eventually made his way to the South Africa lab of Isak Pretorius, a geneticist studying yeast—specifically, winemaking yeast.

“Long story short, I loved it,” Verstrepen says. “A student in a wine lab, learning how to taste wine.” That experience also gave Verstrepen his first sense of beermaking as a biotechnology. “So out went my plans to come up with a cancer vaccine.”

He went back to KU Leuven and got a Ph.D. in applied biological sciences, with a minor in beer. After stints at MIT and Harvard, where Verstrepen co-created a wildly popular freshman seminar that used beer and brewing to teach basic biochemistry and bioengineering, Leuven offered him a job studying how yeasts work, from brewing beer to manufacturing pharmaceuticals. No one is doing more to link beer’s sociocultural history with its high-tech, nonalcoholic future.

Much of the equipment in Verstrepen’s lab is designed to help understand yeast’s chemical outputs. Refrigerator-size analytic engines can discern aromas and flavors with molecular precision. A seven-foot-tall translucent cabinet contains a miniaturized assembly line, bristling with robot arms dabbing at tiny dishes, each executing thousands of tiny chemical reactions all at once. Verstrepen, tall and lean like a cyclist and wearing avant-garde eyeglass frames, is an expert at cracking yeasts open to see what they can do.

De Schutter’s team tasked him with finding a yeast with a very specific set of skills, and back at his lab, he had a freezer full of a thousand different kinds of yeasts—a genetic library of untapped potential abilities. The lab’s high-throughput screening technologies could flip through them like an old Rolodex, looking for the right skill sets. “You don’t have to know the underlying genetic mechanisms,” Verstrepen says. “You just have to find good parents.”

Anyone who follows horse racing or the Westminster Kennel Club understands breeding. But in horses and dogs—or even barley—generating traits you want and sifting out those you don’t can take years. Not yeasts. They pick up new genes as casually as we might change shirts. And they breed fast. Consider how quickly a sourdough starter overflows its jar.

Combine strains with interesting traits, grow them, test them. If you want one that’s resistant to high temperatures, just put them all into a hot bath. “One survives. Guess what? That’s your champion,” Verstrepen says. “With flavor, you do a small fermentation and measure the flavor components—or do a tasting, which is more precise. So that’s what we do.”

Verstrepen’s team started out with more than a thousand candidates. Weeding out the ones that still made too much alcohol got the list down to about 20. Like a lot of wild yeasts, most of the survivors also produced phenols—molecules that, depending on your childhood, remind you of either dirt or Band-Aids. “Phenolic character is typically something we accept in a specialty beer but not in a lager,” De Schutter says. They cut those too.

That left them with just two candidates. Unfortunately, one manifested a tendency to kill any other yeast it came into contact with, thanks to its acquisition of a viral gene for a vicious toxin. That wouldn’t matter unless the new yeast got into a legacy batch. But since they planned to make nonalcoholic beer in the same breweries as alcoholic ones, they’d have to eliminate the trait. They couldn’t risk unleashing a cereal killer.

After a few final rounds of heat-treating to stamp out the toxin gene, the champ emerged: an ancient cerevisiae collected from plants in Southeast Asia, yeast’s evolutionary point of origin. It had a stable phenotype. It ate simple sugar but didn’t consume maltose, and so it made only the teensiest amount of alcohol. It wasn’t phenolic. It didn’t want to murder other yeast.

As a last hurdle, De Schutter’s team took the yeast to AB InBev’s brewery in Mexico, home to a massive fermenter capable of brewing over 300,000 gallons at a time. Flavor is fine, but it had to scale. When you make 15 billion gallons of beer a year, there’s no room for a dilettante. This yeast delivered as advertised. The company nicknamed it Smart Yeast, and started brewing.

Belgian beer is very traditional, but the tradition is constant experimentation. This is the point Yvan De Baets wants me to absorb as we sit in the pub attached to his brewery, Brasserie de la Senne, on an industrial stretch of the Brussels Canal near the trendy Gare Maritime. Designed by De Baets and his business partner, it’s a concrete-walled beer cathedral, with giant windows showcasing all the steel tanks and pipes next door. We’re sipping a beer called Petit Boulba, his version of a low-alcohol brew. At 2.5 percent alcohol by volume, it’s bright, hoppy, and cheerful. “I did that selfishly, to save my liver,” De Baets says. “I never worked so hard on a recipe in my life.”

As De Baets tells it, Belgian beer has always refracted styles from around the Continent. In 1516, Bavaria enacted what was effectively an early national food-safety law, the Reinheitsgebot, or “purity order,” mandating that beer, a critically important regional foodstuff, be made only with water, barley, and hops. Belgium combined this Bavarian rigidity with English facility into lower-alcohol “sessionable” brews and southern styles full of winelike esters. The oldest Belgian beers, like the lambics, relied on “spontaneous fermentations,” using ambient yeasts with funkier, weirder flavors. When trade introduced ingredients like anise, coriander, or the peel of the bitter curaçao orange, Belgians threw them into the mix.

It makes sense, in other words, that Belgians would be working on the nonalcoholic future of beer—brewing innovation is inextricable from the culture. It’s the home of meccas like the Saint-Sixtus Abbey, whose Westvleteren 12 is by some lights the best beer, period. In the city of Bruges, a brewery founded in 1565 constructed a two-mile underground beer pipeline from its brewery to its bottling plant, so that its trucks wouldn’t disturb the medieval downtown. You have to respect a country where every individual brew has its own specially shaped glass.

Alcohol tax policy, fashion, and new science can all redirect the development of emerging styles—“a sociology of taste,” as De Baets elegantly puts it. But he worries that nonalcoholic brews will always be missing a certain something. “The techniques are way, way, way better than even 15 years ago,” he admits. “Still, I believe the base product is not so appealing.”

And yet the runaway success of the nonalcoholic craft brewer Athletic suggests that may just be the connoisseurship talking. Not only is Athletic the biggest NA brewer in the U.S., it’s the country’s 18th largest brewer overall, with 2024 sales of $130 million and a valuation of $800 million. One big reason is that people actually like to drink it. Athletic is notably closemouthed about how it makes its beer, unusual in an industry known for cooperation and openness, and it’s still a munchkin compared to AB InBev. But it’s persuasive proof of market. And as an added economic inducement, it’s legal for brewers to advertise NA brands alongside popular sports like Formula One racing. They can appeal to the mainstream in ways that even the King of Beers can’t.

Smart yeast may solve a specific corporate problem, but the idea—the concept of new yeasts for new beers—might transform the way we think about flavor writ large.

Even with all the high-tech analytic and sensory equipment in Verstrepen’s lab, assessing something as complex as beer requires the nose and tongue of a trained human expert, someone capable of describing its characteristic aromas with poetic precision, using a shared, quantifiable vocabulary where this term means that smell—toasted caramel, grapefruit rind, sourdough bread—to define the various distinct sensations in a single sip of beer.

That’s not me. I’m just a writer who has consumed a lot of beer. Nevertheless, Verstrepen has invited me to sit in on an evaluation of a couple of the candidate yeasts he’s working on. It’s time to drink beer, for science.

His team tucks me into a private study carrel, like one you’d find in a library. I am served amber glasses of beer with numbers affixed to them, and a sheaf of worksheets that gives me SAT flashbacks.

It’s harder than it sounds. Both beers taste like, well, beer. But the worksheets want to know much more. I’m supposed to rate their maltiness, on a scale of one to nine. But also: Is it malty like cereal? Or like bread crust? Or caramel? Is it hoppy like grapefruit or like pine resin? Any smell of banana? Do I detect sulfur? (Actually, one was more sulfury.) I check boxes frantically. My reporting notes say only “I’m too slow!” These are the subtle differences between a mind-blowing transnational (nonalcoholic) beer of the future and one you’d pour down the drain.

In 2024, Verstrepen’s team chemically analyzed 250 Belgian beers and crunched data from 180,000 online reviews, which they then combined with judgments from the lab’s trained panel—the ones I sat in with—and used machine-learning algorithms to detect commonalities. The Belgian beers that people prefer are all likely to have higher levels of protein, lactic acid (the sour in sour beers like lambics), and the molecules ethyl acetate (a kind of solvent-y, chemical smell) and floral, honeyed ethyl phenylacetate. Add a concoction of those notes to a nonalcoholic beer, and people will say they like it just as much as a regular one.

Verstrepen says he hopes the mixture of aromas his machine-learning work has produced will go beyond creating poststructuralist beerlike sensations. He wants to rescue nonalcoholic wine too. And after that? I tasted a formula he’s working on for nonalcoholic gin. It was close, down to the warming sensation. “The model gave us components that I wouldn’t have thought about,” he says. Sure, I say, but the warming thing—it’s the pain and heat sensors in the trigeminal nerve. I venture a guess that he did it with capsaicin, which is what makes chili peppers hot.

Verstrepen hesitates. There are millions of dollars at stake here. He says only that it’s not chili pepper, and then he clams up.

He’s not the world’s only yeast whisperer, after all. Big commodity yeast companies—yes, that’s a thing—sell maltose-negative strains similar to Smart Yeast. A California start-up offers genetically engineered versions that could add even more bespoke flavors to a beer or wine while cutting out the alcohol. The nonalcoholic beers that emerge will be something wholly new, maybe even something delicious and wildly popular … but then is it really still beer?

That’s something De Baets hinted at over drinks at Brasserie de la Senne. “I really believe that alcohol belongs to beer,” he said. “There is no beer without alcohol.”

Obviously, De Baets acknowledged, alcohol can be addictive and has all kinds of potential societal costs. But for millennia, humans have enjoyed having conversations with each other while their minds are slightly altered—a little less suspicious, a little more relaxed—and we need them now as much as ever. “You see what we’re living in today,” he said. “The world is a catastrophe. We need to rebuild those high-quality connections.”

Of course, the people eagerly downing NA beers in bars and at parties probably feel the quality of their connection is just fine. And people who don’t drink alcohol for health or religious reasons deserve a beerlike product that actually tastes good. The market wants what it wants.

I left Belgium with a souvenir: a bottle of Smart Yeast Negra Modelo from the table in that AB InBev tasting room. I carried it home in my luggage, wrapped in T-shirts. On a warm afternoon a couple of weeks later, I cracked it open, and it was still good. I still liked it. I wasn’t trying to fix our dystopia. I was just having a cold beer.

A version of this story appears in the February 2026 issue of National Geographic magazine.