You may have heard the saying, “you can’t square a circle”, which is essentially metaphor for trying to do the impossible. Yet, world-renowned illusion researcher Kokichi Sugihara of Meiji University has uncovered the solution to this problem.

Unlike the more common approaches of studying illusion such as human psychology and cognition, Sugihara has taken a mathematical approach to understanding illusional depth. Unraveling the mathematical side to illusion, Sugihara believes, would potentially decrease the hazards of optical illusions, in situations like driving for example.

For 42 years, Sugihara has worked on devising mathematical formulae to prove the existence of “impossible objects”: 3D recreations of illustrations representing geometric motion that cannot physically happen. The three-time winner for Best Illusion of the Year has produced 500 mathematically-designed deceptions to date.

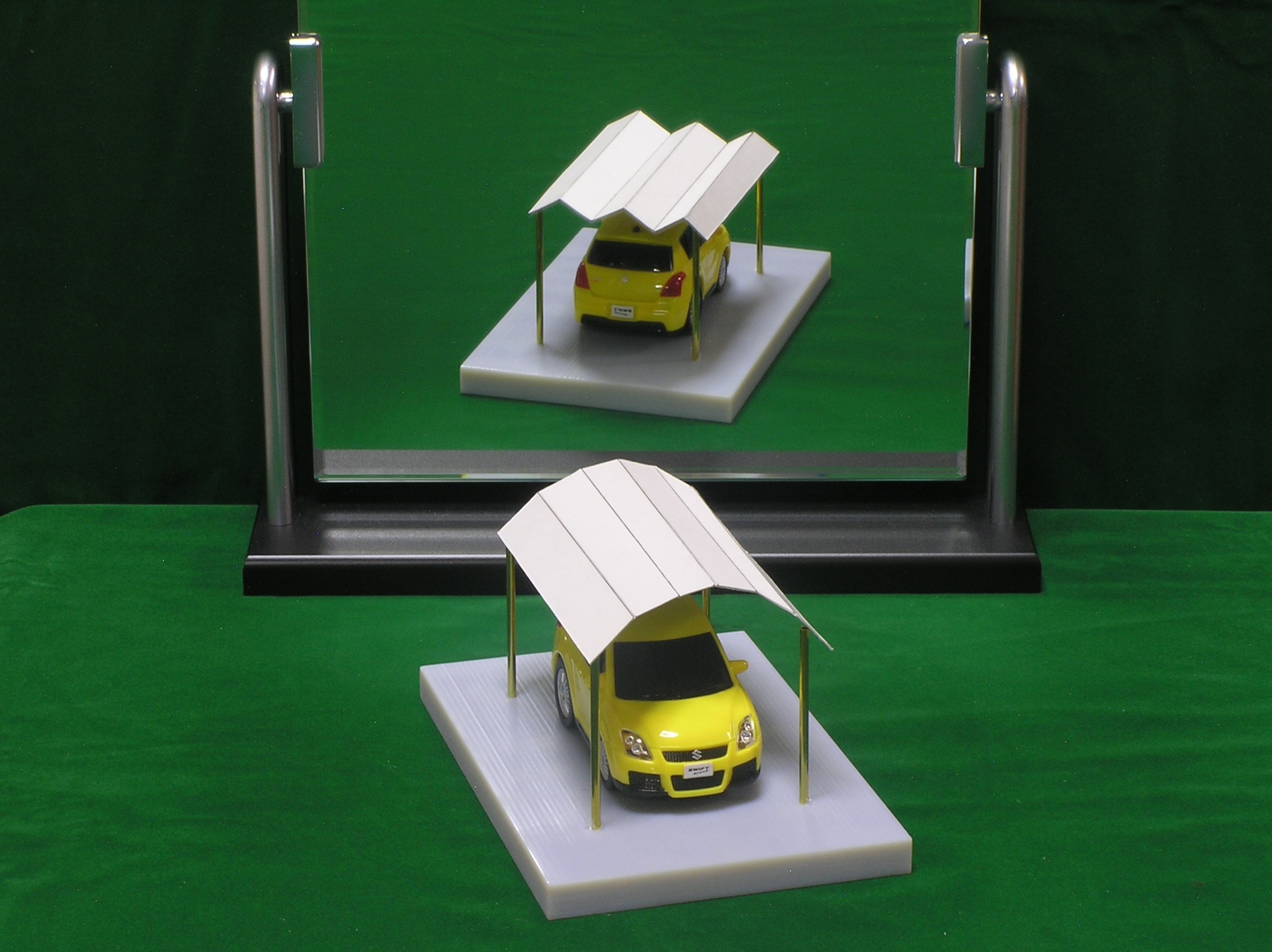

Take for instance the illustration of two L-shaped blocks. Given the thickness of each block, it is inconceivable that such intersecting blocks could exist in reality. This is because when the brain tries to picture three-dimensional structures out of two-dimensional images, it can only make out objects with faces that are connected in 90-degree angles – like structures we are used to seeing in real life – rendering it “impossible” recreate physically. Or so we think. The disconnect is due to a lack of depth perception and such impossible objects can be demystified once viewed from a different angle.

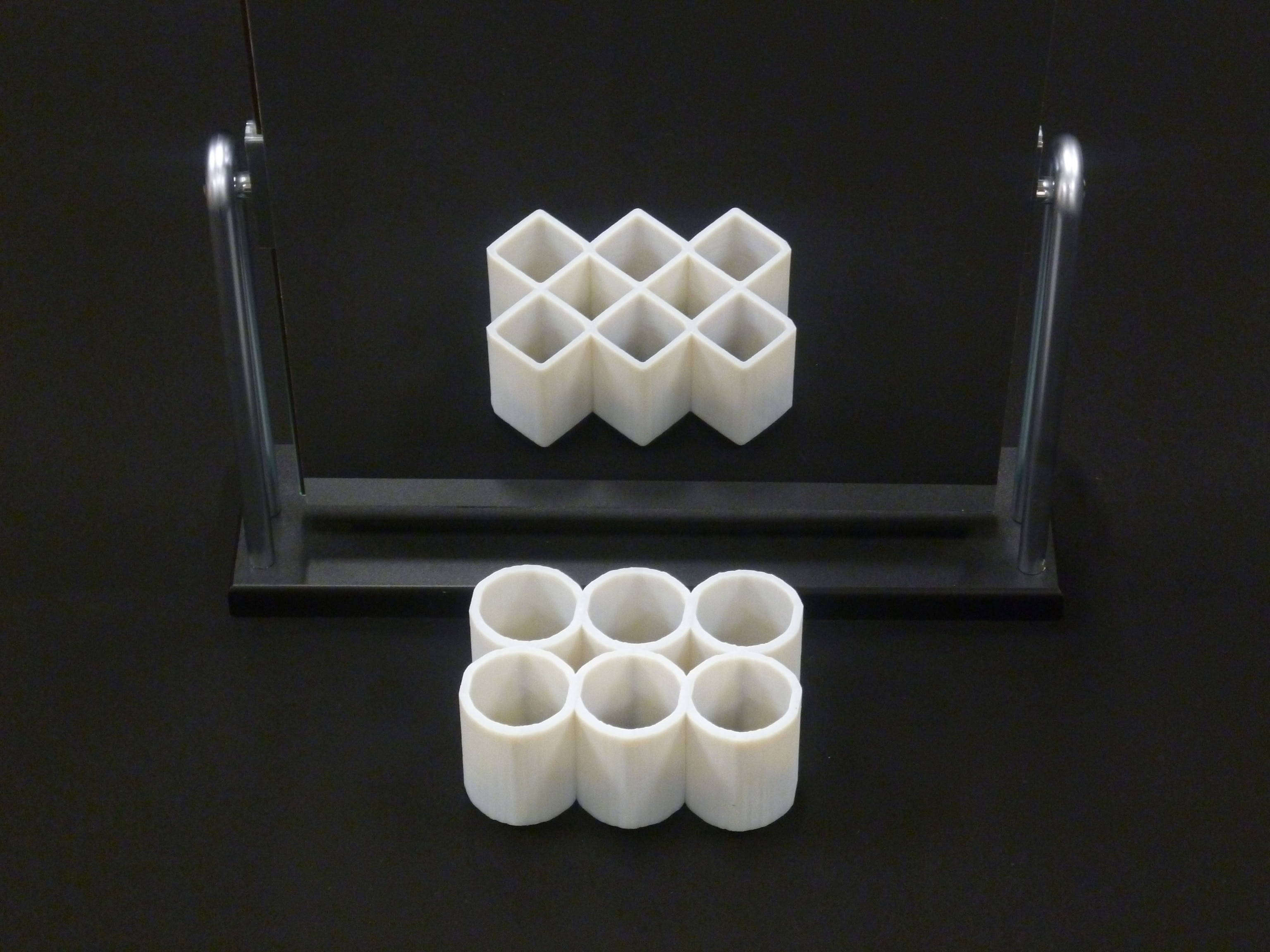

Another area of Sugihara’s research is “ambiguous objects”, which includes the groundbreaking study of a square-circle visual paradox. Cylinders that originally appeared round magically appear squarish when viewed in the mirror.

“How can an object be both square and circular?” Sugihara asks. “The existence of such geometry-defying objects warns us of the potential dangers of optical illusions in our lives.”

Beyond static displays, Sugihara has also demonstrated how physical objects in the real world can sometimes behave in unexpected ways.

Consider four slopes that appear to extend downwards from a common centre. When marbles are dropped on each slope, they appear to defy gravity by rolling uphill. No magnets are involved in this bizarre phenomenon, Sugihara assures; all that was needed was a play on the human visual system.

Sugihara explains that as the human eye tends to interpret illustrations using right angles, the columns supporting the four anti-gravity slopes are perceived to be vertical. Even if we come to realize that the columns are in fact not vertical, we cannot “unsee” the illusion because that is how the brain is wired.

Such bewildering trickery has given rise to “impossible motion”, a term coined by Sugihara in the mid-1990s. The famed mathematician has since created 50 examples of impossible motions including a yearly life-sized snow sledding display at the Hakkai-Sanroku Ski Resort in Niigata, Japan.

Besides convincing mankind that such impossible objects do exist, Sugihara’s research has paved the way for potential applications such as enhancing road safety and equipping robots with better vision. However, he firmly believes that there is more to discover.

“While I have proposed countermeasures to help reduce optical illusion, especially on the roads, there are many other factors at play such as human psychology,” Sugihara observes. “More research needs to be done.”