How breast cancer research is helping prostate cancer patients

Decades ago, doctors created a test to determine which breast cancer patients should receive hormone therapy. Now, researchers are using the same tactics to advance prostate cancer treatment.

For decades, oncologists treating prostate cancer patients were operating in the dark. They knew that adding hormone therapy to radiation treatment could kill cancer cells more effectively than radiation alone. But for some patients, this addition didn't help them live longer or improve their outcomes—and it also subjected them to hormone therapy's menopause-like side effects.

“Each patient has their own unique cancer, so how do we figure out which treatments are best for which patients?” asks Daniel Spratt, department chair of radiation oncology at University Hospitals’ Cleveland Medical Center.

Now, for the first time, a genomic test for prostate cancer can help answer that question. For patients who experience a cancer recurrence after removing their prostate, the test predicts who would benefit from hormone therapy and who can safely skip it. To develop the test, Spratt and his collaborators took a page from the breast cancer playbook.

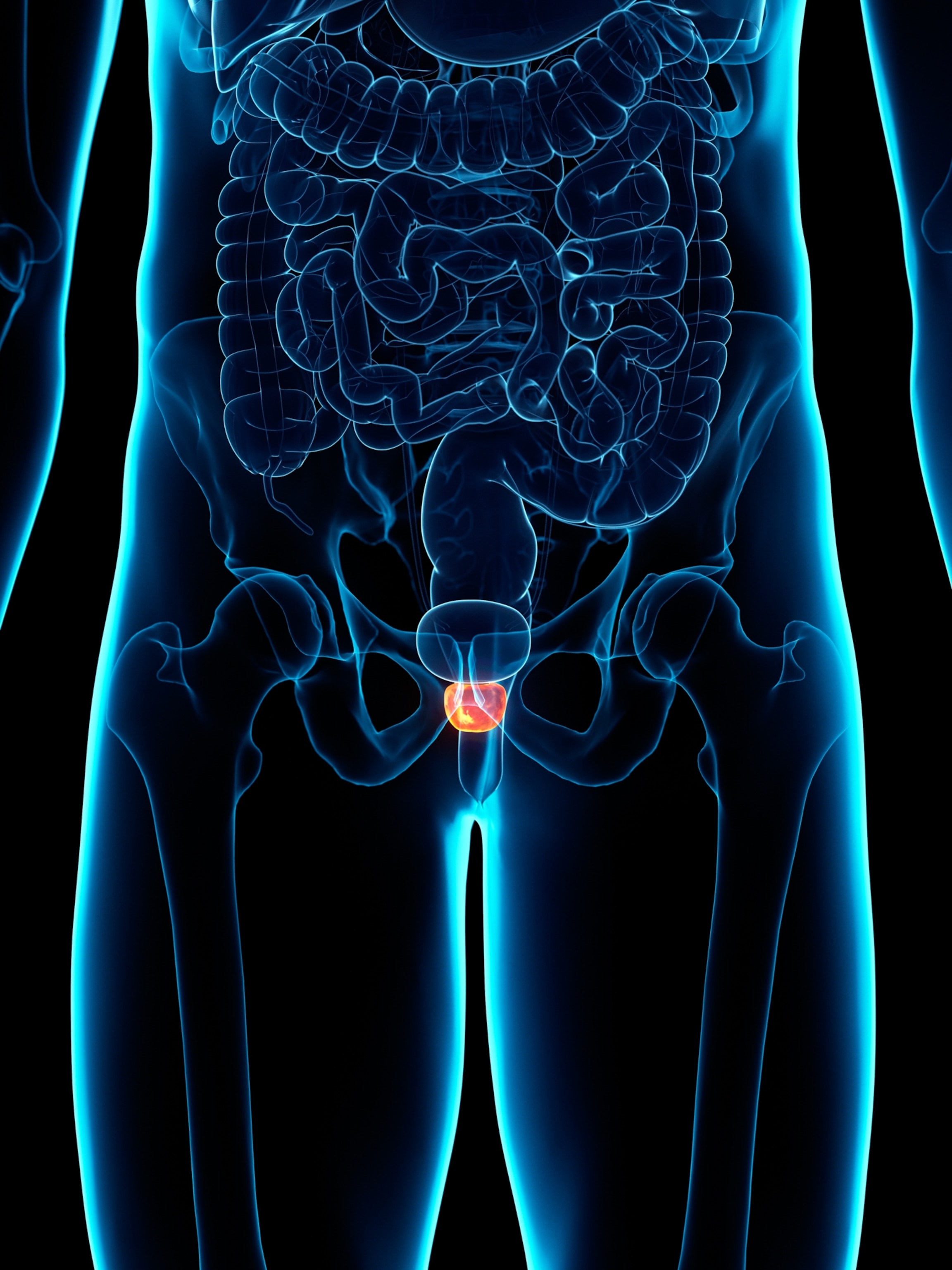

How prostate cancer recurrence has traditionally been treated

When prostate cancer returns after surgery, doctors must decide whether to treat it with radiation alone or add hormone therapy. Historically, they've relied on clinical factors like the time since surgery, the tumor's appearance under a microscope, and PSA, or protein, levels in the blood, which help screen for prostate cancer.

(Prostate problems are incredibly common. Here’s why—and how to treat them.)

But this approach can be subjective. "Some [doctors] give it to every single guy. Some give it to very few men," says Spratt.

The result is inconsistent care, leading many patients to endure hormone therapy's harsh side effects, including bone loss, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and mood swings, when they may not even benefit from the treatment at all. Long-term hormone suppression also raises the risk of heart disease, cognitive issues, and metabolic disorders. The same was true for breast cancer patients, until researchers discovered how to categorize their tumors.

How scientists found success with breast cancer

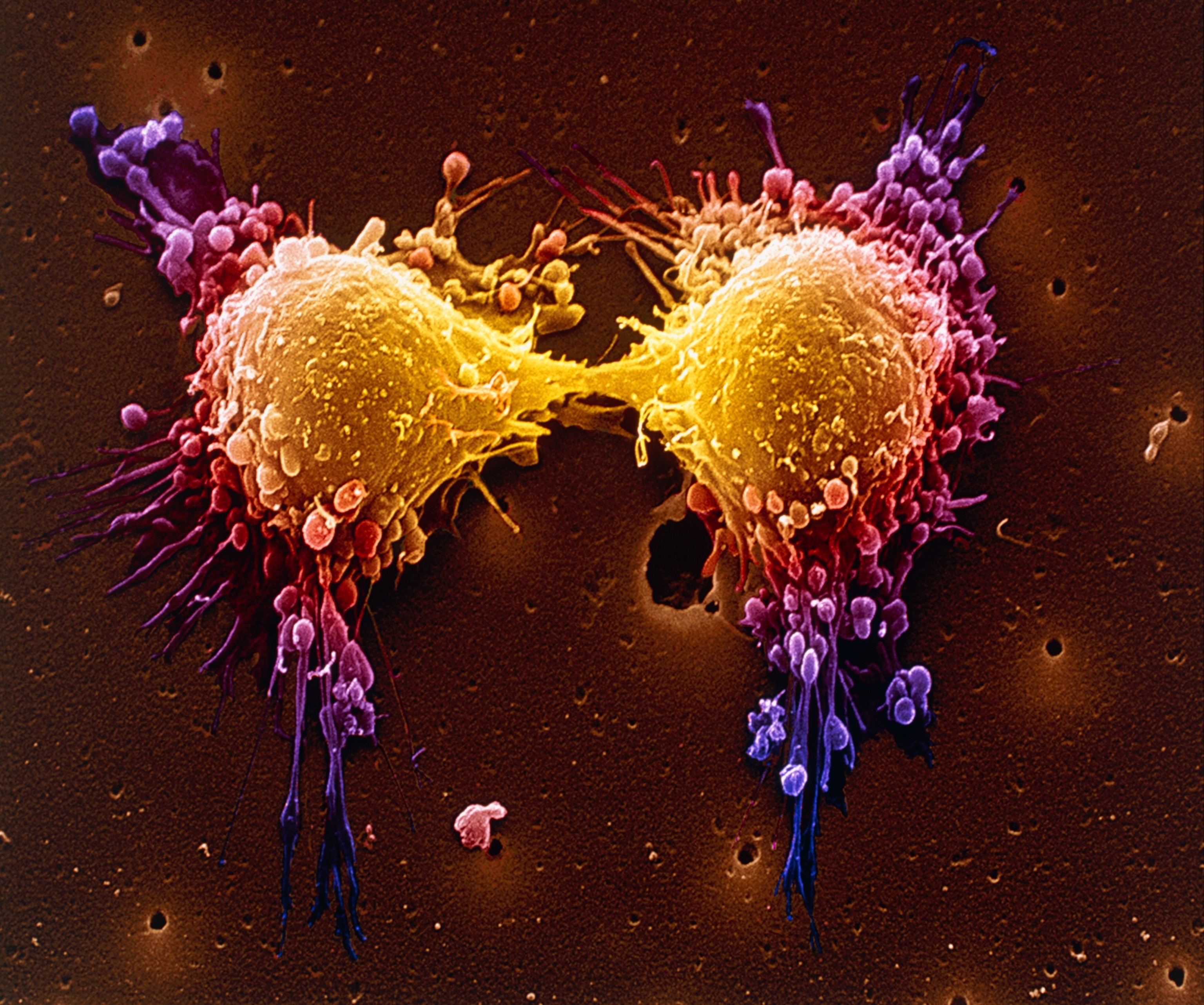

Like prostate cancer, breast cancer can be fueled by hormones—specifically, estrogen and progesterone. These hormones latch onto cancer cells, activating genes that make the cancer grow and spread faster. Hormone therapy blocks this action, which in turn hinders cancer growth.

But some types of breast and prostate cancers can grow in other ways, making hormone therapy useless. For patients with these cancers, hormone therapy brings only side effects, without any of the benefits.

Breast cancer doctors solved the “question of who should get hormone therapy decades ago with a simple test. Designed by pathologists, the test uses antibodies that latch onto estrogen or progesterone receptors, marking them so that they're visible under a microscope. “Any patient with a tumor that is hormone receptor-positive, we pretty much always recommend hormone therapy,” says Jo Chien, a breast cancer researcher and physician at University of California San Francisco.

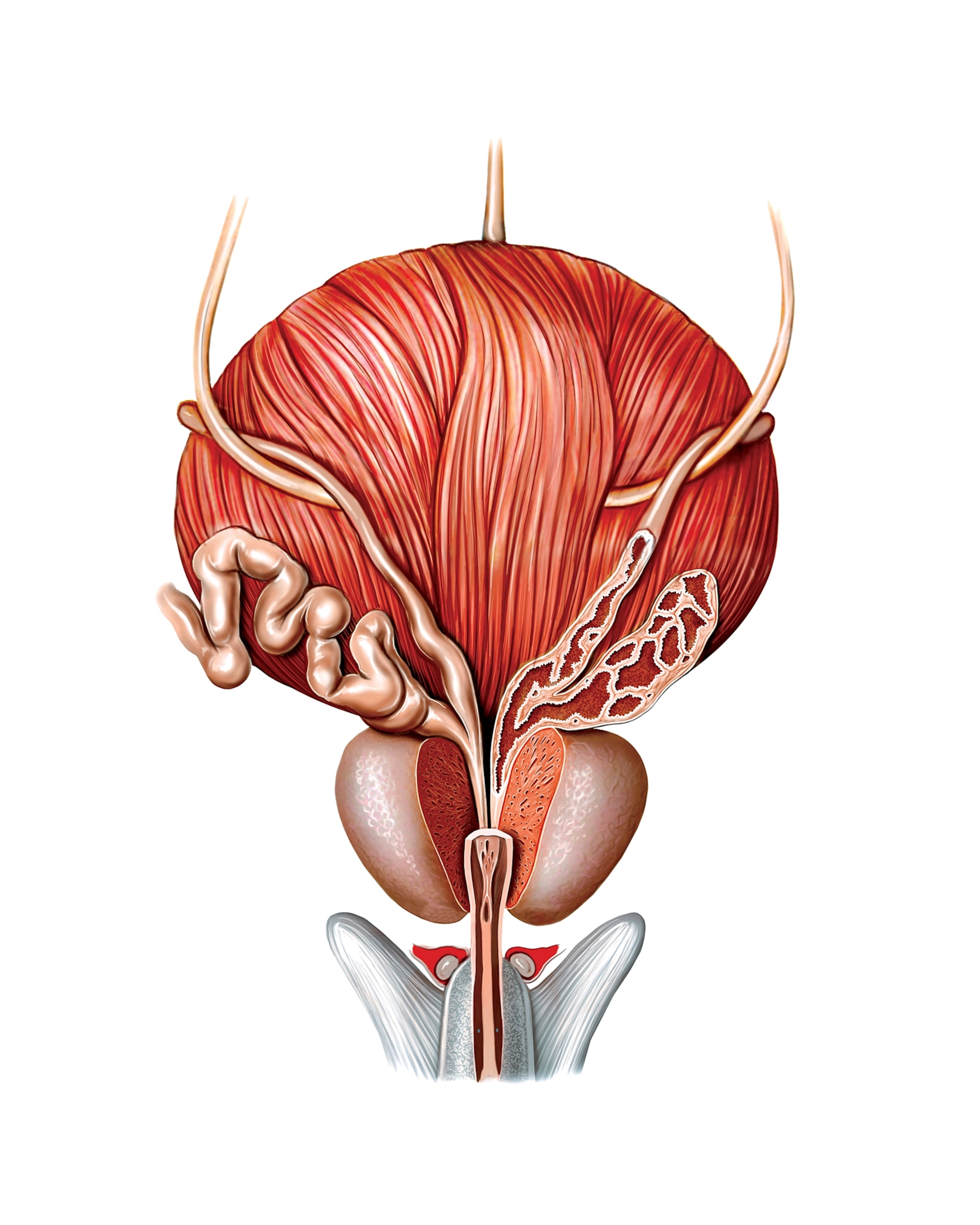

Cracking the case for prostate cancer, however, has proven more complex. Up to 99 percent of prostate cancers have hormone receptors, yet many don't depend on hormones to thrive. Testing whether cancer cells have hormone receptors, therefore, can't distinguish which patients stand to benefit from hormone therapy.

Instead, scientists decided to look at how active a tumor's hormone receptors are—or how effectively they turn on genes driving cancer growth—to help determine whether hormone therapy will work. But detecting this required advances in testing technology, such as the genomic tests that soon began to refine breast cancer diagnostics. “For prostate cancer, it's taken a lot longer to get to the same point" that breast cancer has, says Spratt.

Since scientists first started testing tumors for hormone receptors, categorizing breast cancers has evolved dramatically. Genomic tests can analyze which genes are turned on in a tumor, providing a readout of how aggressive the cancer is. Tumors with similar gene activity tend to act alike, so by examining this signature, doctors can predict how a patient's cancer will behave.

One such test, developed in 2002, can predict whether a breast cancer tumor will spread within five years. While traditional assessments based on tumor size and other clinical factors were accurate up to 60 percent of the time, this genomic test correctly classified 83 percent of tumors.

(Cancer vaccines are showing promise. Here’s how they work.)

And breast cancer care has only become more personalized over the last decade. “We profile tumors extensively because there are different pathways for treatment for all of the different subtypes within subtypes of breast cancer,” Chien says.

PAM50, for example, is another genomic test that analyzes 50 genes to classify breast cancers into five subtypes. Knowing a tumor’s subtype helps doctors determine a patient’s prognosis—how likely the tumor is to spread, how aggressive it will be—and tailor their treatment accordingly.

How tests are being adapted for prostate cancer

Physician-scientists, noting the similarities between prostate and breast cancers, repurposed PAM50 to differentiate prostate tumors. “Although it's not perfectly overlapping, a number of genes are similarly expressed in prostate cancer,” says Spratt. He and his collaborators have since refined and optimized the test specifically for prostate cancer.

"We're trying to determine the right amount of treatment for the right patient,” says Robert Dess, a radiation oncologist at the University of Michigan and a co-investigator on the PAM50 study. “We don't want to overtreat or undertreat them.”

Using PAM50, the researchers identified two distinct groups among patients whose cancer had returned after prostate removal. One group had fast-growing tumors with highly active hormone receptors, which were addicted to testosterone. “They're more dependent on testosterone, so when you give hormone therapy that lowers it, these cells feel it much more than other subtypes of prostate cancer,” Spratt says. The other group's hormone receptors, on the other hand, were much less active, and their tumors far less responsive to hormone suppression.

In a clinical trial, participants were randomly assigned to receive either radiation alone or radiation plus hormone therapy. Crucially, the trial was also double-blind. "I didn't know what my patients' PAM50 scores were, nor did I know what medicine they were on," says Dess.

When researchers later analyzed the results by tumor subtype, a clear pattern emerged. Patients with testosterone-reliant tumors who had received hormone therapy alongside radiation fared significantly better: 72 percent remained cancer-free based on blood tests after five years, compared to 54 percent who received radiation alone. But for patients with less hormone-sensitive tumors, hormone therapy made virtually no difference: 70 percent remained cancer-free with hormone therapy compared to 71 percent with radiation alone. Adding hormone therapy didn't move the needle for this group at all.

Given the trial's promising results, the company that manufactures PAM50 plans to begin offering the test this year to help guide treatment decisions. “I think this will become a standard of care test in the U.S.,” Spratt says.

(Colon cancer is rising among young adults. Here are signs to watch for.)

Other experts are also intrigued by the results. “It’s a big advance for the field because hormone therapies do have side effects associated with them,” says Rahul Aggarwal, a genitourinary oncologist at University of California San Francisco, who was not involved in the PAM50 research.

What lies ahead

The next step is to confirm the trial’s findings with other patient populations: Can PAM50 help select optimal treatments for newly diagnosed patients with intact prostates, for example, or for patients whose cancers have already spread?

And while genomic tests are an important piece of the puzzle, researchers are also investigating other, often faster avenues to bucket tumors with greater precision—such as employing artificial intelligence to analyze digital pathology slides of cancerous tissue. But traditional methods to grade prostate cancer are still valuable too. "We put everything together to help us make good decisions," Dess says.

Spratt envisions a future where hormone therapy can be eliminated entirely, replaced by theragnostics—an injectable form of radiation that seeks out and destroys prostate cancer cells from within the body while sparing healthy tissue. It's more precise than the typical external beam radiation, which must be carefully aimed at the tumor from outside the body. His team is currently testing this approach in an ongoing clinical trial, with some promising early results.

After years of limited treatment options, it's an exciting time for prostate cancer research. “Looking at genomic and imaging-based biomarkers to personalize therapy is definitely where the field has been and will continue to move towards in the upcoming years,” says Aggarwal.